The Understudy

Every working actor on Broadway nods conspiratorially when you say you’re “covering” for another actor on Broadway—usually a famous one. They know that 1) you’ve got bills to pay, 2) you need the weeks to gain your health insurance through Actors’ Equity, or 3) you’re actually interested in the play and the artists involved.

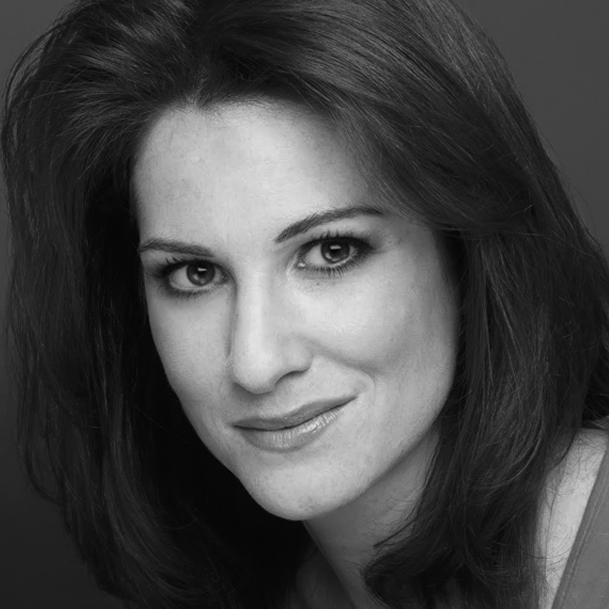

When I was asked to understudy the extraordinary Eve Best and Kelly Reilly in Pinter’s Old Times, starring Clive Owen, I thought it might be a kill-three-birds scenario.

The first time I watched a run-through in the rehearsal hall, I thought, “What the hell have I signed on for?” If you know this Pinter one-act (is there anyone out there who knows it?), you know that when it comes to the past, the “truth” is negotiable. Shared between three old lovers, it can be contentious, heartbreaking, and violent. Pinter never makes his intentions, or those of his characters, clear. He says, “The past is what we remember,” and has all three characters telling stories that don’t match up, performing in stylized, disjointed arias. Could I be more vague? Yes, if I were Harold Pinter. But I watched the run-through and felt as though those artists had climbed Everest.

As an understudy, I only started rehearsals four weeks after the onstage cast. That’s four weeks of conversations between the actors and director that I didn’t hear, where agreements had been made, secrets aired, and memories created to fill those famous Pinter pauses. In that first run-through I watched, I saw all sorts of work, but didn’t begin to know where it had come from. I was being paid to go away and fill in all the blanks.

I think good understudying means being in service to a piece of theatre. You spend hours, days, weeks watching the play like a hawk: first in rehearsal, then in tech, and then during previews. You watch how and where they move, how they speak, when they steal a sideways glance… You watch and watch so that you know in your bones what has been created up there on the deck. There are those rare times when you think a moment could be clearer (i.e. better) but you need to have the grace to let it be what it is, to honour it. To be in service is to ignore the desire to “improve on” anything. Just identify what has been built, and go away and build a reasonable facsimile.

About four weeks after I started, during the last week of previews, I had the play down. I knew all the lines for both characters, I knew the paths they travelled on the stage, when they took a drink or lit a cigarette… If one of the actors had gotten sick, I could have walked onto the stage, said the right lines in the right order, and at least nobody would die. The bare minimum had been achieved.

But the really hard work lay ahead; nobody wants to watch a parrot on stage. I needed to personalize all the decisions that I was recreating. So I went back to the script and asked myself what I would feel/do/say in any given moment, had I been the actor in the role. I gave myself permission to ignore the current production for a bit and wade around with those words and my own thoughts and spirit. It was remarkably liberating, and the result was a deeper connection to the characters. I went from being like them to inhabiting them. And all those discoveries I made I then wove back into the proper music of the piece.

There’s a psychological component to the job when it comes to managing your expectations. You hope to get onstage so that the work you’ve done can be seen and appreciated. But you don’t want to go on if it means some disaster befalling the actor you’re covering. Bad karma. Bad actor-karma. And then there’s the possibility of that last-minute call telling you the actor is stuck in traffic at the airport… or whatever… and you’re on in 90 minutes. Honestly, my greatest concern was that I wouldn’t have time to blow dry my hair or shave my legs. I could imagine no greater horror than Clive Owen running his hands over my unshaved leg. That was a recurring nightmare.

After a couple of months of rehearsing and putting in hundreds of hours of non-rehearsal time, I felt a particular kind of exhaustion. It was the exhaustion of doing nothing, of being ready… but doing nothing. It had become difficult to motivate myself to work on sections of the script, or watch the show, or do a line run with the other understudy. There is a point where the psyche says, “You’re never going on, so just give up.” I knew the consequences of apathy; I considered that I was still picking up a cheque, and if I did go on, the joke would be on me if I had ceased to be prepared.

If you have to perform as an understudy, and you go on the stage and say the right lines in the right order, and stand where you’re supposed to stand, you’re already a bit of a hero. I know; I’ve done it. You feel like you’ve saved the world with your acting.

On the other hand, if you don’t get to perform, there ain’t no glory. You learn the thing, that honking amount of work, and then it closes. The potential for frustration and disappointment is enormous. I know that too, as I’ve seen it in other actors. I think the antidote to frustration or apathy is the “being in service” bit. It doesn’t just keep you honest about your reasons for signing on; it offers a great big opportunity for growth. In Old Times, I essentially did a three-month workshop with the world’s authority on Pinter, Douglas Hodge. And they paid me to do it. I worked my imaginative tools, as well as my speech and diction. And I am an absolute thief: I have stolen tools and tricks and attitudes and accents and jokes from award-winning actors. You figure out what they’re doing that you’re not and think, “I wanna be able to do that too.” It ups your game.

Despite all this, I was surprised by how I felt the day of our closing. I was antsy and distracted. I watched the final performance with irritation. After the final curtain we had a company party, where I said some quick goodbyes and then bolted for the subway. I could not wait to get out of the building.

It took me a few days to let this feeling sink in. It was the pang of unrequited love. I had fallen in love with that play and those characters, and we never had our proper time together.

Comments