Acting Normal

The day she started rehearsals for Soulpepper’s It’s a Wonderful Life, Michelle Monteith was in high spirits. It was November 8, and like so many people (and polling organizations) in the world, she was confident that Hillary Clinton was about to be elected president. That milestone felt meaningful, especially because she was sharing it with her young daughter. “I couldn’t even fathom that Hillary wasn’t going to win,” she said. “It just seemed beyond any possible thought that I had.”

By the second day of rehearsals, the world had changed. Monteith listened to Hillary Clinton’s concession speech in the car on the way to work in a state of utter shock. When she arrived and saw her colleagues, no one knew what to say. “Gregory Prest was the first person I saw. We didn’t say anything, we just hugged.”

Their task at rehearsal that day was to watch the movie version of It’s a Wonderful Life, the classic Christmas heartwarmer about the importance of hope and resilience. On November 9, that was difficult. “It was the last thing I wanted to do,” she said. “I only wanted to talk about what was actually happening.”

* * *

Post-election social media was a confusing hybrid of sage advice and smug, gleeful hate speech. It seemed best to try to avoid it. But when I did look at my Twitter feed, one particular message caught my eye, courtesy of Pussy Riot: It’s like being arrested. Dramatic at the beginning. But then you start to figure out how to live and create in prison. You’ll overcome. In the two months since the election, it feels like one of the most insightful observations from that night, one of the most accurate. In that time, we’ve all heard the once-unbelievable phrase “President-elect Donald Trump” so many times that it doesn’t seem strange anymore. Soon “President Trump,” too, will stop sounding wrong and become something that’s ugly but commonplace, like rot on the side of a building you walk by every day. As we all brace ourselves for the next, unknowable chapter in American history, I’ve been thinking more about the day after the election: how it felt surreal, nightmarish, walking around on that cold sunny day and feeling like the world was an evil place.

I’m not an actor. I’m a writer and an editor and a student. If I retreat from my work for a couple days because I’m struggling with fears I don’t know how to contain, that mainly affects me. It affects my grades and my relationship with editors to whom I’m on deadline. It affects my co-editor, May, who has to pick up my slack. But the impact is largely private: it happens behind closed doors. Actors, though, don’t have that luxury. They have to get up onstage, with a spotlight pointed at them and strangers watching, and remain composed and productive and present even if they’re experiencing trauma. How is it that something people can do? How is that Michelle Monteith and Gregory Prest can tell a hopeful story like It’s a Wonderful Life when it feels like things are beyond hope? Even if the work is unrelated, how can actors get up there without the weight of their emotions crushing them completely?

There are other professions that require more focus; being an actor isn’t like being a surgeon or an air traffic controller. But few jobs require the level of presence that’s demanded of actors. Many of us go through our lives with all kinds of emotional distractions just below the surface: we have days where we’re dealing with family issues or relationship angst, or days where we just feel off. But actors can’t just feel sad or snippy or lethargic; they can’t be distracted. They have to get onstage and be someone else, without any of those emotions showing.

* * *

As the cast of It’s a Wonderful Life was beginning rehearsals, Chala Hunter was gearing up for her opening night. She was starring in Storefront’s production of Beaver, which began its run on November 11. Before the show opened, she wrote bravely and beautifully about how that female-focused show often isn’t recognized for the hero’s journey it is. Beaver is about the beauty and the trauma of growing up a girl, about longing and growth, about women learning to cut the tethers that exist between them and the men who seek to control or diminish them. It’s not outwardly political, but it’s filled with the kind of characters whose lives, in Trump’s America, would be politicized.

Chala Hunter, left, with the cast of Beaver. Photo by John Gundy

When we spoke on the phone the week after the election, we were both still processing the news. Her voice was firm and clear, even when what she was talking about was total defeat. “I’ve been thinking about [the election] on and off, all day,” she said. “I wonder if my work can ever be enough, or be valuable. There are these sneaky little stabbing things, these little moments where I feel so insignificant in my efforts.”

In some ways, she said, working on a play at all felt trivial. But the enormity of what had just happened in the world also gave the work a gravity it may not have had otherwise. She said the show’s material allowed her to explore her personal moments of anguish, to work with that feeling, in a way that another show may not have. Her character experiences doubt of that kind; the play itself questions how women are seen in the world. That questioning granted her access to her character in an immediate way. “Who is Beaver? Who is this twelve-year-old girl? What is her experience in this story? It’s a part of this feeling I’m having, related to Donald Trump: I’m thinking about millions of young girls, and older women, too, feeling disempowered and trapped. How can I represent the character with the most amount of humanity, truth, clarity, and vulnerability, so that that story fills its full view?”

Her theatre school training helped her to do that, to channel her own sadness into feelings her character might have. The model of turning pain into art has always been a part of how she’s understood the acting process. “My dad died about a month before I started at the National Theatre School,” she said. “I’ve always focused harder during times that were difficult.”

* * *

The role of an acting teacher is often interrogative: in order to teach students that kind of focus, you have to teach them to ask questions. A few minutes into my conversation with acting coach Rae Ellen Bodie, she stopped me in the middle of a question so that she could ask me about my experience. She wanted to know how it had felt, physically, to receive the bad news on election night. “What were you feeling in your body?” she asked. “Were you feeling scared? Were you feeling angry?” This is what it’s like talking to her: she’s curious and considerate, plugged into the feelings of everyone around her.

In her work, she often focuses on the physical experience of emotion. The day after the election, her class started with a long discussion about how everyone felt, about their fears for the future. After everyone had spoken, she led her students through an exercise to connect the way they were thinking and feeling to the physical sensations of their bodies. The ability to identify how emotions are processed physically is a big part of an actor’s toolbox, she said. Exercises like these are the first step towards students being able to “process and make art out of those feelings of sadness and anger and despair and fear,” she said. Eventually, “you can marry the present feeling with the fiction that you’re working on.”

The process of channeling negative energy into a character or a story is difficult for me to understand, but it’s part of the alchemy of theatre. Bodie said that exercising that muscle, difficult as it can be, is a way to make good work. “When we don’t take the feelings that we’re having—these strong feelings of despair and sadness and grief—and activate them, then it actually makes us stop moving,” she said. “So we sit, we pine, we sleep, we don’t leave the house. Acting is about performing actions. If I become inactive, there’s no story. It’s over. Acting will move a person away from despair and anger, or despair and sorrow and grief… Because I take the feeling and I do something with it.”

That kind of help often means identifying a connection between what’s happening in an actor’s real life with what’s happening in the world of the play. Hunter and Monteith both say the connections they found to the material they were working on helped them counter their sense of helplessness. Hunter said that even though her work sometimes felt small and insignificant, its granularity made it more urgent, too. “Does it matter?” she asked. “[Beaver is] an almost all-female play that’s vaguely being paid attention to in Toronto. Does it matter for Trump? Fuck no, obviously not. But does it matter potentially for a lot of the men and women who come to the theatre?” This is a different kind of a question, she said, and it’s hard to answer. Often she did feel that in a small way, within her community, the show felt significant.

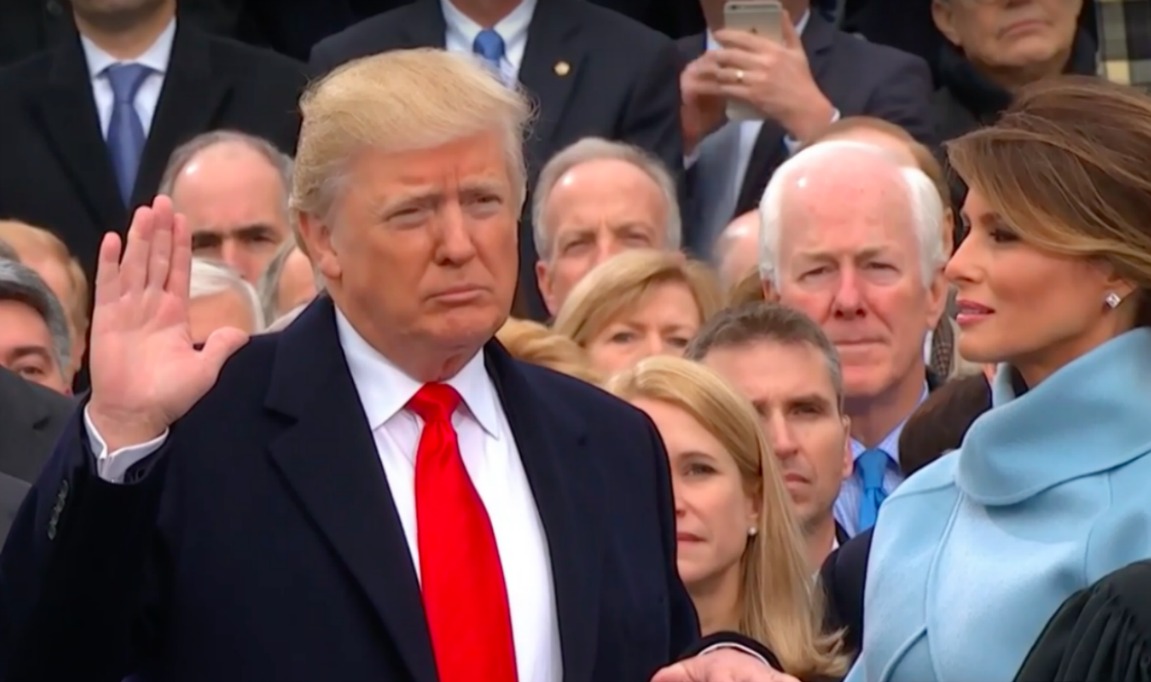

Diego Matamoros as Mr. Potter and Gregory Prest as George Bailey in It’s a Wonderful Life. Michelle is in the back on the far left. Photo by Cylla von Tiedemann

For Monteith, watching It’s a Wonderful Life on November 9 connected her understanding of the multiple characters she played in the show to the inescapable confusion and dread she felt that day. Drawing on the similarities between the real world and the world of the play allowed her to turn her sadness and fear into productive energy; she could focus on work while processing some of that darkness. “It’s a way of coping and of escaping, all at once,” she said. There’s more to the story than the hopeful ending everyone remembers. Despair and greed and disenfranchisement live in that story, too. For all the ways the world has changed since 1946, the similarities felt prescient. Many audience members saw Trumpisms in Diego Matamoros’s portrayal of callous banker Mr. Potter, for instance, even though Monteith said he never tried to highlight any connection. “It was so much in our thoughts that that’s what people would see and hear,” she said. “He didn’t say ‘make America great again,’ but he may as well have.”

For Bodie, there’s both sadness and comfort in the fact that old stories continue to resonate in new ways; that contemporary audiences can connect with material written decades ago. “We keep telling the same story down the ages, because we keep, as human beings, making the same stupid mistakes as we were forty years ago, a hundred years ago, two hundred years ago, five hundred years ago,” she said. “We have to keep telling each other the same fucking story. So, to be reminded by the election of Trump that what’s happening now existed then, existed then, existed then, it’s like—we’re all just kind of carrying each other through it by telling each other these stories.”

* * *

Another post-election tweet that’s stuck with me came from Imani Perry, a professor of African-American studies at Princeton. Recognize your country for what it is, she said. No fictions.

Monteith said working on It’s a Wonderful Life right after the election of a man who is supported by the KKK, who brags about assaulting women, shone “a full-on spotlight” on some dynamics that exist even in her own life, things she never had to confront before. The play, in combination with a show she starred in in the spring—Wendy Wasserstein’s The Heidi Chronicles, which examines the absence of women in so much of the world’s history—have changed the way she sees the world.

“I think if you had asked me before, I would have said some of the things that women have fought for, you know, we have those things.” Because misogyny is “insidious,” she said it was often hard to see before. But not anymore. Working on these shows fundamentally changed her view of the world. “I either put on a pair of glasses, or I took glasses off,” she said. “But the way I see the world has completely changed, and I can’t unsee it. And it’s not necessarily made me a happier person.”

Clarity of that kind is difficult to know how to confront head-on. A lot of people feel helpless against the rising force of blatantly racist and women-hating authoritarianism, and actors aren’t immune. Like everyone else, they can make small changes: Monteith talked about being more aware of a tendency to take up less space than the men in the room, to work on combatting that in herself. Hunter also wants to encourage that kind of awareness. “There’s this vehemence that I feel about giving women a voice in the world, at least in the Toronto theatre community,” she said. But the additional tool actors have is an invaluable one: a creative outlet. I still don’t know how it is that anyone can get up onstage and ignore all of those emotional distractions. But that act, which looks so difficult to me, is just one part of a healing process. Doing creative work affords actors a privilege many people don’t have. “What do you think they’re doing on Bay Street right now, as the stock market is going insane and nobody knows what’s going to happen?” Bodie asked me. “How do you think they’re all dealing with it? Sneaking conversations by a coffee pot in a staff room?”

The day after the election, after guiding her students through the physical exercise, Bodie said she felt much better, too. For over an hour, she and her students had communicated, had gotten the chance to connect when they all felt scared and raw. “And then you go out of the room and there’s a bit of—a bit of hope, or a bit of relief,” she said. “Or maybe no relief at all, but the fact that you’re angry and sad and in despair has been acknowledged. There’s a group of people who go, I feel you, dude.” She paused. “We get to do that. You and I get to have this conversation, because of what we do in the world.”

Comments