Don’t Cast a White Actor as MLK, and Other Reasons It’s Important to Listen

“If we see something wrong, it’s great to point it out and say ‘no.’

The next step is, what do we do about it now? What can I do about it now?”

– Nina Lee Aquino (Artistic Director, Factory Theatre)

The battle for greater diversity in theatre is not being fought on my body. I’m a tall, thin, white, cis, able-bodied, queer male, and no matter how strong an ally I am, I understand that my body will always afford me a significant amount of privilege. I’m not using my privilege to excuse myself from the conversation, but to understand that my voice in the conversation needs to be one of humility rather than authority. That said, I have noticed a troubling trend. Often during otherwise-productive conversations around diversity, someone (usually a similarly-privileged artist) will state with authority, “Well, the best actor should just get the part.”

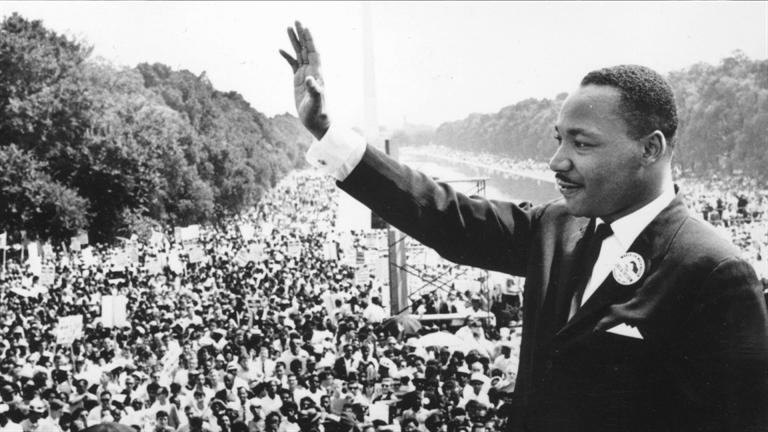

In theory, yes, the philosophy that “the best actor should get the part” is artistically sound. It could open the door for a myriad of inclusive, “non-traditional” casting choices. Unfortunately, in practice, it’s usually employed as a defense of traditional casting, or, worse, an excuse for casting privileged actors in roles written to create space for actors from specific, underrepresented, populations (e.g. Kent State University’s casting of a white actor as Martin Luther King Jr. in Katori Hall’s The Mountaintop).

The existence of “the best actor” is not an objective truth, and we need to stop treating it like one. When we talk about the “best actor” we are discussing an imaginary embodiment of those traits we most value. Unfortunately, for many, the “best actor” is still straight, white, cis, able-bodied, thin, and classically trained, unless chosen to be other. This is not going to change until we collectively put in the hard work of acknowledging and challenging our own biases and how they influence our practice.

My show Bodies Strange involves ten characters that will be performed by an ensemble of five actors. When casting, I nixed the traditional headshot/resume submission and asked all applicants to write a short letter expressing why they were the best actor for a particular member of the ensemble. In the call for submissions, I took out any language that would indicate age, sex, or ethnicity and identified all five roles for which I was casting with a single letter. Historically, I have been guilty of mentally tallying the number of underrepresented bodies involved in both mine and other artistic projects as a measure of their diversity. With this project, I have approached diversity in qualitative terms, considering how the process and, by extension, the production are enriched by the presence of artists whose lived and embodied experiences do not resemble my own or each other’s. I do not want to claim the bodies of my collaborators as tokens of how “progressive” my practice is; rather, I want to be grateful for and respectful of the varied perspectives they bring to our collective effort. This is not easy work, and my practice is far from perfect. I am still working, especially on listening.

Harsharan Sidhu, Kyle Capstick, Annie MacKay, Alexi Pedneault, Larissa Currie, Jordi O’Dael, Carlos Albornoz, and Kelly Anderson in Bodies Strange. Photo by Jonathan Harvey.

Listening helps me learn how we can collectively improve in order to support all members of our community. I believe this improvement won’t happen until we stop arguing about the best actor and start listening to the ways artists from diverse backgrounds and experiences are telling us they are being disserved or excluded, asking their advice on how we can improve, and then doing the work.

I spoke to three such artists about their experiences and asked for their advice for how I, as a privileged artist, could improve.

1 – An actor who would rather remain nameless

The first person I spoke to was an actor of colour (who has asked to remain anonymous) who provided the following insights:

“Before submitting for auditions I usually consider the team (director and actors), the script (is it amazing?), and the part for which I am being considered. For me, with the muscles I am looking to stretch and exercise, blind submissions are not going to garner fulfillment. If the company is largely white, I know I am entering a contract where it’s possible they won’t understand my everyday lived experience, and they may also direct me in a false societal assumption of what they expect my race and gender should be projecting to them.

I once had a male director say to me, ‘The character is a woman in a man’s world. So think about that. I am not believing it.’ I almost rage blacked-out. I am a woman in a man’s world—EVERY woman is. I could just stand there and fulfill that requirement. Beyond that being terrible direction, he wasn’t interested in unpacking what being a woman in a man’s world meant. He wanted a general wash, a whiff, a scent in his very specific projection of what that is or means to him, not what it means to me.

My experiences as an actor have made me wary to put myself at the disposal of someone who I am not sure I can trust to understand me

My lived experiences as an actor and general sense of rehearsal has made me wary to put myself at the disposal of someone who I am not sure I can trust to understand me, to not paint me or my culture into a box, or to not tell me what the third world represents to them. Often I play Indians (as I am south Asian). The Indians I am playing are all in the third world, and it leads to awkward conversations with directors about class (this is often revealing of their antiquated notions of the third world). As much as I like to have intellectual conversations, it sucks, it’s exhausting, and it’s not my job. I have to decide every time I submit whether I want to subject myself to this.”

2 – Nina Lee Aquino, A.D. of Factory Theatre

Second, I had the privilege (and joy) of sitting down with Nina Lee Aquino, the artistic director of Factory Theatre. She gave me the following advice:

“Get to know the community holistically. Go beyond what you know. Start un-defaulting (your default of ‘Oh, I know this director’s great I’m always going to see their work’). Try. That’s the thing, once you start supporting theatres that do believe in interculturalism then your mental library of actors, designers, directors, and playwrights who are beyond what you know grows and it becomes diverse naturally.”

3 – Angela Sun

Finally, I spoke with one of my favourite collaborators, the actor of colour Angela Sun. I’ll conclude with her advice:

“First, for a company to hire me, they would first have to find me. Companies who really want a diversity of performers should advertise diversely and seek out other listings than just the industry ones. They should also be specific in their character descriptions—emphasize that a character can be “ANY ethnicity/size/gender” or, better yet, produce work from diverse creators who write about people of colour/women/different identities. Finally, people need to put their money where their mouth is. I should not be walking into an audition waiting room where I am the only actor of colour. If you are afraid you won’t get enough actors out, ask your friends for recommendations or go out to see shows by companies that have a good record of hiring diversity and steal their creatives. When I see your production—if I am not in it—I want to see colour front-and-centre on your posters and in lead roles. In short, predominantly white companies need to put in the extra work (and stop complaining about it) because the ‘diverse’ performers you are looking for face extra barriers in this industry. And trust me, the effort is worth it.”

Further Readings:

- Thoughts, by Shaista Latif

- A Token of Our Depreciation, by Tanisha Taitt

- I’m a black actor. Here’s how inequality works when you’re not famous, by Bear Bellinger

- This Is What It’s Like to Be A Black Actor in Canada, by Julian MacKenzie

- Diversity in theatre: why is disability being left out? by Lyn Gardner

Bodies Strange is on at Majlis Art Garden from June 30 to July 10 as part of the Toronto Fringe Festival.

Click here for tickets or more information.

Comments