Changes Are Coming to the National Theatre School of Canada

Gideon Arthurs has a lot to say about responsibility. As the CEO of the National Theatre School, he’s concerned with the school’s responsibility towards the students it’s educating, and towards the theatre community where those students will land. He thinks about NTS’s responsibility for representing the needs of a diverse country that hasn’t always looked clearly at its own history. And he also feels that theatre might, in a small way, be responsible for saving the world. “I have this belief that theatre is a force for good in the world today,” he says over the phone from his office in Montreal. “Theatre is going to be one of the antidotes to the kind of radicalism and divisiveness of our times.”

These are ambitious ideas. But, as anyone who’s spoken to Arthurs knows, he’s convincing.

NTS announced today that the school is implementing a four-year growth plan that will offer more programs and broaden the reach of some of the existing ones. Among other things, the school will launch a program aimed at fledgling artistic directors, expand its Indigenous artist-in-residence program, develop programs for young people, and provide more professional development and master classes.

Gideon Arthurs. Photo by Maxime Côté.

The school’s identity as a national institution plays into several of these decisions, Arthurs says. He’s excited about the new Artistic Leadership Development Program, which will sit alongside the school’s existing program streams: acting, directing, playwriting, production, and set and costume design. Because there are no equivalent artistic development programs in Canada, Arthurs explains, artistic directors who retire or move on will often be replaced by American or European counterparts. “Look at what happened at Harbourfront, Luminato, the Shaw Festival,” Arthurs says. “A lot of those jobs bypassed Canadians. There hasn’t been any development opportunity for younger leadership. It’s not that we have less talent, but they just haven’t had the chance to put their hand on an organization yet.”

The school’s new plan also aims to address reconciliation with Indigenous communities. “As a national institution, we have to understand that there’s a third pillar that needs to live at the National Theatre School, and that would be Indigenous culture, as opposed to just our current binary, which is English and French,” Arthurs says. NTS has already implemented an Indigenous artist-in-residence program, with dancer and choreographer Carlos Rivera in his first year of a two-year residency. Arthurs is looking forward to continuing the project with performer and storyteller Sheena Akoomalik from Pond Inlet, Nunavut, who will work on her directorial craft at NTS next year.

As important as that addition is, Arthurs is conscious of how critical it is to work in slow collaboration. “I think we have a long way to go before we understand what role we can play,” he says. “What we want to do is build the school’s vocabulary and its relationships with the Indigenous artistic community.”

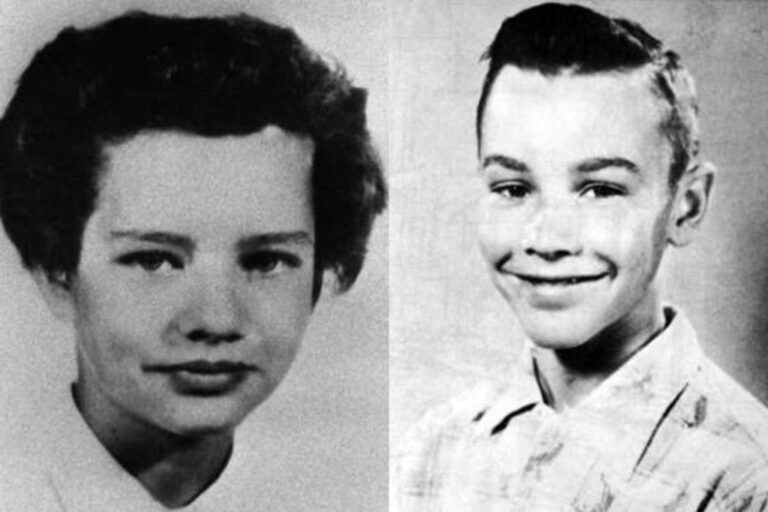

Sheena Akoomalik and Carlos Rivera. Photo by Marie-Ève Rochon.

Inclusion is another one of NTS’s responsibilities. Because of the school’s sizable resources, the weight of its reputation, and the very small size of its classes, Arthurs says the admissions committee is responsible, in a real sense, for deciding who will populate the country’s stages a few years down the line. Nearly half of the students in this year’s graduating acting class are culturally diverse, a first for the school. “If we can actually embrace notions of inclusivity and diversity and make room for new kinds of stories, I think, very rapidly, the industry will have the tools it needs to make those changes on its stages,” he says. “We can actually be the genesis of that transformation.”

Defining the duty a theatre school has to its students is part of an ongoing conversation that came back to the fore in part because of an Intermission article by Megan Robinson from February. Although the piece served primarily as a personal essay about a very individual experience at one theatre school, it opened up a wider discussion about the line between constructive academic criticism and abusive teaching practices. Arthurs says the piece wasn’t entirely surprising but was still upsetting to him. “There’s no doubt that that kind of attitude is present in the artistic community, and that it reverberates through training in different ways,” he says. “What that story was about is simply unacceptable. It can’t be allowed to exist. It’s a hangover from a patriarchal age.”

Arthurs admits his certainty in the bright future of theatre doesn’t always remain at the level of preternatural enthusiasm. “Maybe today I’m an optimist and tomorrow I’ll be pessimistic again!” he says. But he’s definitely excited about what’s to come at NTS, and how those changes will resonate in the wider community. “I actually really do believe that the idea of coming together in person and feeling something together is more rebellious now than it has ever been.”

Correction: This article originally stated that more than half of the students in the graduating acting class are culturally diverse. In fact, it is just under half of the class: five students out of twelve. Intermission regrets the error.

Comments