John and the Challenges of the

Actor-Turned-Director

Novice mountain climbers don’t usually start with Everest, but—in a way—that’s just what Jonathan Goad is doing.

Goad is well-known as one of the best and most courageous actors on our stage today, and he’s making his directing debut with a play by the brilliant but difficult Annie Baker: John.

Described by Sarah Larson in The New Yorker as “lessons in empathy… [that] capture the light and shadow of everyday life,” Baker’s dialogue-rich, slowly unwinding scripts aren’t to everyone’s taste, but the minute Goad read John, he knew he had to direct it.

“With a great play like this,” he said on a break from rehearsals, “you realize it speaks to you in a certain way and you ask yourself if you have something to offer the play, to honour it.

“You have to be interested in all the things a play might be saying rather than a singular statement. It has to thrill, delight, and terrify you, but also make you think.”

Set in a quirky B&B in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, filled with antique dolls and an inexplicable sense of dread, the amiable Mertis (Nancy Beatty) welcomes a young couple, Elias (Philip Riccio) and Jenny (Loretta Yu), whose relationship is going through a rough patch.

To that, add Mertis’s blind and eerie friend, Genevieve (Nora McLellan), and dress it all up with stories of Civil War ghosts and carnage.

“I read it and it was a page-turner,” confides Goad. “Even though [Baker] doesn’t write page-turners. She gives us a group of interesting people in a room they’ve been forced into, together. Maybe not with clear objectives and intents, but with loneliness and a desire for love.”

So what happens in the end? Goad’s chuckle has a bit of a sinister edge. “[Baker] does the opposite of what I thought she was going to do. She doubles down on the risks we take in the theatre and I’m prepared to follow her lead.”

Jonathan Goad, centre, in rehearsals for The Company Theatre’s John. Photo by Dahlia Katz

Risk-taking in the theatre. It’s something we all applaud yet sometimes see too little of. But when the person at the helm is an actor-turned-director, the chances of higher stakes somehow increase almost exponentially.

Inspired by Goad’s initial foray into the other side of the table in the rehearsal hall, I asked three other prominent Canadian actors-turned-directors about their journeys down this road: Martha Henry, Nigel Shawn Williams, and Keira Loughran.

Martha Henry is about to start her forty-third season at the Stratford Festival as the director of Twelfth Night. She directed last season’s smash hit, All My Sons, and appeared onstage the year before as the wickedly funny Lady Bountiful in The Beaux’ Stratagem.

After eighteen years as a leading actress at Stratford, she began playing both sides of the fence during the tenure of Robin Phillips, when he asked her in 1980 to direct Brief Lives.

“I suspect he asked me because no one else would take on Douglas,” she says dryly, referring to her ex-husband Douglas Rain, who starred in the one-man show and was notoriously temperamental.

“As an actor, I knew what Douglas needed, but what I had no idea of how to do was work on the physical production of the show. I enjoyed picking the music and collaborating with the designers, but when it came to the lighting, I said to the wonderful Phil Silver, ‘I have no idea what to say to you.’

Chick Reid (left) as Countrywoman and Martha Henry as Lady Bountiful in The Beaux’ Stratagem (Stratford). Photo by Michael Cooper

“Phil replied, ‘Let me be the lighting designer and you just tell me what you want.’ So I’d sit there in the theatre and say ‘I need it to feel more cold,’ or ‘Put some more light in that corner so we can see what he’s thinking.’ And that was it. I wound up loving the lighting sessions and I still do.”

Even though Henry feels that having been an actor informs everything she does as a director, she is very, very careful never to try to insert herself into the proceedings. “I never give line readings,” she says.

But what she had the most trouble doing, she says, was “worrying about how much the actors trusted me and how much they didn’t.

“Until I went home one night and said ‘Martha, they don’t have to trust you. You have to prove you’re trustworthy.’ That was kind of a cold shower for me. It woke me up.”

Her method with actors now is: “Do whatever works for you as long as you’re not hurting yourself or someone else. If you feel you need to stick your head in a pail of cold water before you go onstage, then do it.”

And right now, just before starting Twelfth Night rehearsals, she tries “to live in the world of the play so totally that [she] can help the actors understand everything about it.”

In that aspect, Nigel Shawn Williams is a lot like her.

The widely respected artist, who has won four Dora Mavor Moore Awards, as both actor and director, is very clear about what draws him to directing.

“I love the challenge of finding the truth of a play, telling its story and locating the humanity at the heart of it.”

Kevin Hanchard and Nigel Shawn Williams in Topdog/Underdog (Obsidian/Shaw). Photo by Emily Cooper/Shaw Festival

His directing work, from The Monument to last season’s acclaimed production of A Line in the Sand, has been centred on “taking care of the actors and making them feel safe.”

He feels he came by that passion honestly, “because of the really good directors I worked with early in my career. People like Peter Hinton and Neil Munro… Watching how they took care of actors, helped them, and then told a great story.”

Was it hard to transition from acting to directing? “Not really,” he laughs. “I was always looking at things in a macrovision, not a micro one. [As an actor] I was always aware when a sound cue was coming. I’d be aware that my scene partner had a big moment coming and I’d make sure they had the space to do it in.

In the current 2016/17 season, Williams has starred in the controversial play about cybersex, The Nether, at Theatre Aquarius in Hamilton, directed by Luke Brown, and is about to start staging Yasmina Reza’s Art for The Grand Theatre in London before heading out to Vancouver’s Bard on the Beach to direct The Merchant of Venice.

When asked why he picks such challenging projects, he observes that “the harder the piece, the more attractive it is.”

He also fully intends to keep acting as well as directing. “The type of director that I want to be, I think it’s necessary that I continue to be an actor as well. It’s important for me to be on stage so that I’m a part of the creative process and see how it changes and grows. I have to grow as an actor if I’m going to grow as a director.”

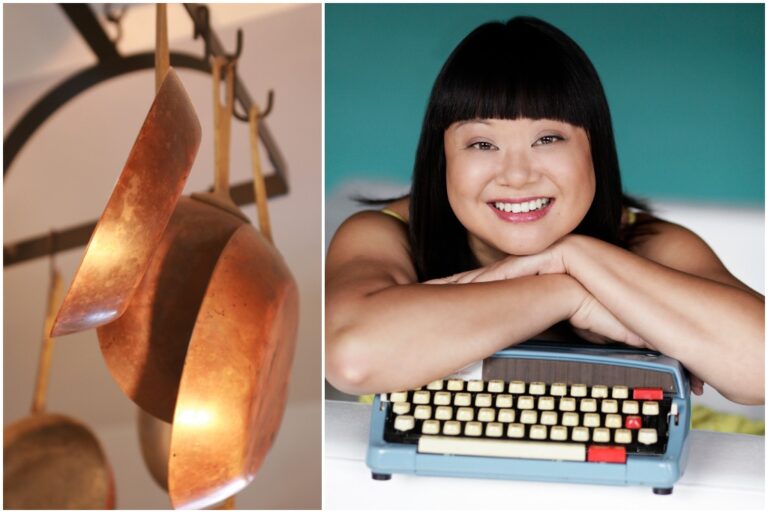

Keira Loughran could easily qualify as a quadruple threat, having known success as a writer (Little Dragon), actor (China Doll), director (The Aeneid), and administrator (currently associate producer of the Forum and the Laboratory at Stratford).

But even though she admits that her first impulse in the art form was always towards direction (“It was what got me into the theatre”), she has come to realize that “once you’ve spent a bit of time in the acting profession, it stays with you.”

Loughran feels the real selling point for her as the director of any production is discovering “the idea of an intention behind a production. What is the world of this play and why are you doing this show? More importantly, why does this play have to be done now?”

Jo Chim, Marjorie Chan, and Keira Loughran in China Doll (Nightwood). Photo by John Lauener

A good example of that is her Stratford production this summer, a new version of Sharon Pollock’s 1975 play, The Komagata Maru Incident, the story of a 1914 affair where an entire boatload of Punjabi immigrants was denied admission to Canada and forced to return home after a long and painful delay with tragic results.

“My process has been very instinctive on this show,” says Loughran, “combining my own experience of racism with the reality of the world today and the refugee crisis that is so much a part of our lives.”

But while putting the big political picture together, Loughran makes sure that she is aware of the experience of each actor, starting at the audition level.

“You want to create an environment where they will feel welcome. No matter how the audition goes, the actor should leave feeling like they’ve really been seen and they’ve had a chance to do their best.”

Once she’s actually in rehearsal, Loughran relies on her own past experience to “try to give direction to an actor that is practically useful. Sometimes, it’s just about giving them space to try stuff out and work on their process.

“I believe in direction as affirmation, because what you’re asking of actors is an incredibly demanding job, in terms of both the vulnerability and the balance between technical skill and spontaneity.”

Whether it’s acting or directing, Loughran applies the same criteria for deciding whether to participate.

“It has to be a project worth doing and I have to feel that I as an artist have something I can contribute to it.”

All of this brings us back to Goad and his direction of Baker’s John.

“Annie Baker sets the tone for us,” states Goad. “We must make art that has value. We may fail, but we must try. We must do something that may be mysterious but will also be enriching. We’re going to do the best we can in the time we’ve been given.”

Comments