REVIEW: Hannah Moscovitch’s Red Like Fruit is what minimalist theatre should be

Content warning: this article discusses child sexual assault and gender-based violence, and contains spoilers.

The feminist movement needs a dose of medicine, and 2b theatre’s world premiere of Hannah Moscovitch’s latest work, Red Like Fruit, is a horse pill. This tight, 80-minute piece is a bone-chilling exploration of sexuality, gender dynamics, and authority. Performed in Halifax’s black box Bus Stop Theatre, the play appears casual, but in this humble package, Moscovitch asks some big questions: who controls the narratives of the lives of women, or, more aptly, who do women let control the narrative?

Directed by Christian Barry, this two-hander follows journalist Lauren (Michelle Monteith) as she recounts her time writing her latest article. The crucial twist is that Lauren does not tell the story herself. She has written it in the third person and given it to Luke (David Patrick Flemming) to read out loud to both her and the audience. We never learn how Lauren and Luke are connected, nor why she has asked him to speak for her. Lauren, through Luke, details how her investigation into a single incident of domestic violence has caused her to reconsider her own history with sexual assault.

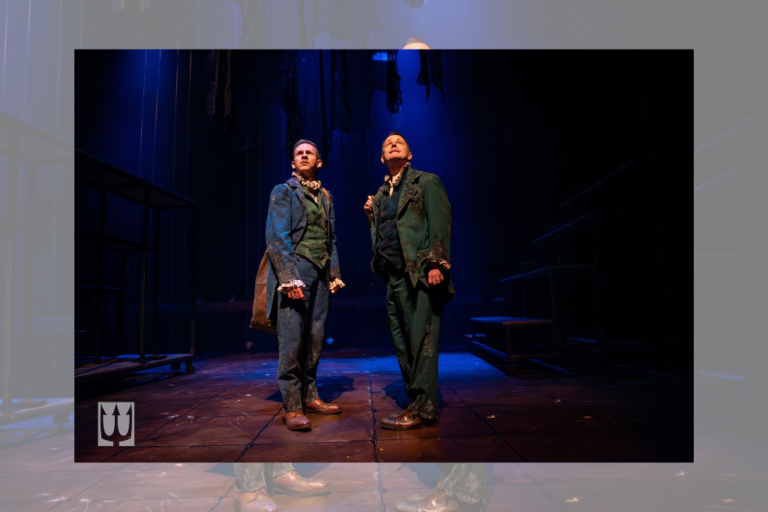

Moscovitch is known for exploring relationships of power in her work, and Barry physicalizes this on stage. The lighting, costumes, and set by Kaitlin Hickey are stark against the plain walls of the black box. Costumes are business casual attire, and the set is simply a raised black platform centre stage, with a single wooden chair in the middle, lit by a soft yellow light. It’s a simple, engaging arrangement that furthers the subversive structure of the premise.

Lauren stays within the confines of the platform, mostly sitting in the chair and acting out the story Luke narrates. She is central, but rarely speaks. Moscovitch’s script plays with the trope of the silent woman by making silence Lauren’s choice, and Monteith brings this to life with vivid expressions that share her inner world. Lauren’s agency is evident. She is not a woman who is silenced by men; her silence is her choice, her way of processing her own story.

Meanwhile, Luke commands attention in a more traditional sense: through his voice. His narration is comedic, but remains disaffected, a performance almost reminiscent of an audiobook. He doesn’t necessarily feel invested in the story — he feels invested in reading it. Barry has Flemming walk a delicate line between an authoritative narrator and a man who seems uncomfortable speaking for a woman. Flemming walks this line with grace, and at times I found myself unsure of which version of Luke was real. My focus was drawn to him almost unwillingly, trying to figure him out, despite my efforts to keep watching Monteith. Words have power, indeed.

Occasionally, Lauren breaks the narration, interrupting Luke or catching his eye with her palpable stress. Some of these moments of connection feel a little stiff, but generally, it’s difficult to tell if the breaks in Luke’s narration are scripted, or actual mistakes in the piece that Monteith and Flemming are covering up with stunning improv. Moments like these blur the line between character and actor, and bring the story into the real world, rather than pulling the audience into the fiction.

As Luke describes Lauren’s investigation, it feels familiar and frustrating. There are men who make jokes about the situation, a victim afraid to speak up, doctors and police who refuse to make hard judgements. It’s not new to anyone who lived through the #MeToo movement, including Lauren, who begins to reflect on her own similar experiences with sexual violence.

The investigation builds to the moment when Lauren talks about being assaulted by her adult cousin in her teenage years. It’s here where Luke’s narration pairs with the show’s most bold lighting change, as Lauren is slowly, subtly washed in red. For a single moment, Lauren becomes her own rapist, as Luke describes her most vivid memory of the incident. But almost instantly, Lauren has moved on, dismissing the weight of the event.

“Isn’t the trauma all part of the experience?,” she asks the audience.

This builds into a larger monologue, when Lauren reveals the questions that haunt her: isn’t it normal for women to face sexual violence? Doesn’t talking about it make everyone uncomfortable? Honestly, what is the difference between sexual assault and sex she realized midway through she didn’t like, or sex she liked but didn’t say “yes” to? After all, when she was assaulted, she didn’t exactly say “no,” so maybe he just misunderstood?

Lauren clearly has put her faith in a man to help her find her own answers to these questions. Have we heard it as truth because it’s her story, or because Luke has told it? Moscovitch challenges the audience to ponder which voice is truly the one being empowered in this play.

This production is stark and simple, jam-packed with big questions about gender, power, and truth. It’s challenging, engaging, and relatable. It’s literally breathtaking, as evidenced by the collective sigh that filled the house of the Bus Stop Theatre as the curtain call began, and we remembered we do in fact, need oxygen.

Red Like Fruit runs until April 21 at the Bus Stop Theatre in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Tickets are available here.

Intermission reviews are independent and unrelated to Intermission’s partnered content. Learn more about Intermission’s partnership model here.

Excellent review! Saw the show yesterday