For the leadership at Crow’s Theatre, investing in local talent is crucial

If you’re a Toronto theatre fan — or if you have one in your life — you’ve probably heard a thing or two about Crow’s over the last two years.

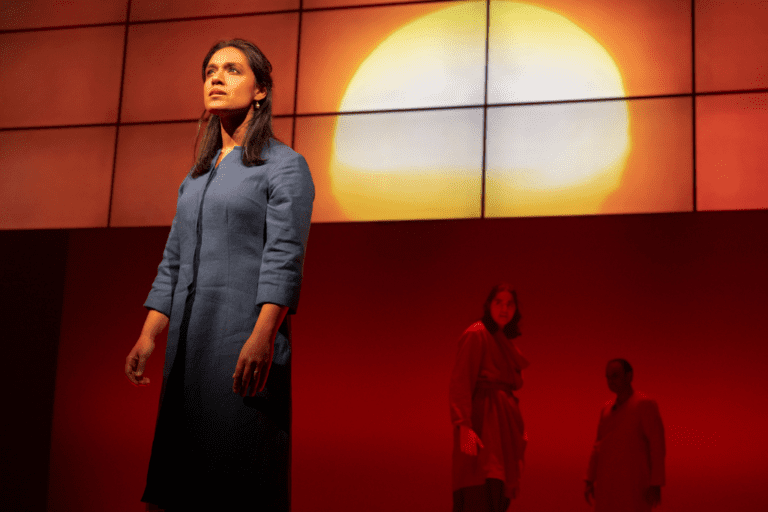

The 41-year-old company consistently sells out its runs, and in recent years has garnered rave after rave from Toronto critics. For Canadian theatre enthusiasts, Crow’s is impossible to ignore — it’s been behind some of the city’s buzziest post-pandemic productions, from The Master Plan, about the infamous Sidewalk Labs fiasco in Toronto, to Natasha, Pierre & The Great Comet of 1812, a co-production with Musical Stage Company that became a local phenomenon over the course of its run.

Both of those shows have since been picked up for remounts with partner companies. The Master Plan will travel to Theatre Aquarius before returning to Toronto for a production at Soulpepper, and Natasha, Pierre & The Great Comet of 1812 will close out the 2024-25 Mirvish season. Plus, just announced this morning, Crow’s Theatre’s beloved production of Fifteen Dogs has been programmed into the 2024-25 Off-Mirvish season, following a successful run of the play at the Segal Centre in Montreal.

“We were looking to bring our most successful shows to bigger places,” said artistic director Chris Abraham in an interview at Crow’s. “We knew there was definitely an appetite to bring Fifteen Dogs and The Master Plan back. But to do that here would mean that not very much else could go on at Crow’s. So we were looking for ways to find a bigger audience for these shows.”

It’s far from the first time Crow’s has created a pipeline for its work from the Guloien Theatre to other stages. Last year, Crow’s lauded production of Uncle Vanya headed southwest for a run at Theatre Aquarius before returning to Toronto as part of the Off-Mirvish season. And As You Like It, a radical retelling has toured across Canada and beyond, including a local remount in last year’s Off-Mirvish season. It’s a trajectory that works well for Crow’s, introducing its work to new audiences while giving established fans a chance to re-engage with the work they loved the first time around.

“Torontonians responded so strongly to those works — Fifteen Dogs and The Master Plan — because they felt there was something those shows saw about Toronto,” said Abraham. “We noticed that. We saw that the new work we were doing was connecting with our audiences. So we have a bunch of plays — some of which appear in this upcoming season, and some that are at different stages in their development — that we’re looking forward to bringing to audiences.” In the years to come, audiences can expect several more page-to-stage adaptations at Crow’s, with an emphasis on Canadian literature old and new.

Associate artistic director Paolo Santalucia says he’s cheered by how strongly the city showed up for Crow’s over the course of this year, and with the recently announced Crow’s season, he’s looking forward to continuing that trend.

“It’s been really invigorating to see how the public has absorbed and embraced Canadian talent across the last few years,” he said. “I think that’s indicative of the fact that audiences are excited by the talent pool we have here. One thing we can do as a Canadian theatre centre is make strong advocacy for encountering prestige, Canadian talent, and allowing that to meet the public in a vital, exciting way.”

“We’ve seen that sometimes spending a little more money — on cast, on the production values behind the show — can turn into audiences, which in turn means we can afford to take bigger risks.”

According to Santalucia, the upcoming Crow’s season is a “beautiful case study” for what happens when an institutional emphasis on Canadian work meets the level of talent Toronto theatre has access to.

“We’re staging brand-new, commissioned works at scale,” said Santalucia. “We have the capacity to see a cast size comparable to that of Natasha, Pierre & The Great Comet of 1812, but in the context of a new Canadian play. We’re very lucky, and humbled by the fact that we’re able to do that, and commission works with ensemble casts and see those through to production.”

Large-scale new work raises financial questions, of course: big casts cost money. But according to Abraham, there’s a certain level of risk theatre companies need to take if they want to keep elevating the industry’s standards.

“It’s a priority,” said Abraham. “One of the bigger lessons we’ve learned over the last couple of years is that sometimes spending a little more money — on cast, on the production values behind the show — can turn into audiences, which in turn means we can afford to take bigger risks.

“One of the downsides of an ecosystem that’s been trained to work within a public funding box is that you get used to working with what you have,” he continued. “Coming back from the pandemic, and having some extra resources to play with, helped us make the decision to go bigger than we’d ever gone before in terms of numbers of shows, size of cast, et cetera. We didn’t know how that would go. But bigger casts, and being able to tell stories with larger groups of people, particularly in an intimate theatre setting — audiences seem to really respond to that. It’s nothing against a great one-person show — we’ve done lots of them — but giving playwrights the opportunity to start to work on a bigger canvas has been really important. Plays happen differently when you start to add more characters.”

“We’ve learned what can occur when you put a large group of people in a room — you’re talking about a really fundamentally communal, community-driven experience between the art and the public. And that’s something we’re really inspired by right now.”

One of the commissions being produced at scale is Michael Ross Albert’s The Bidding War, about the local housing crisis and featuring a star-studded ensemble cast of Toronto actors, including Aurora Browne, Sergio Di Zio, Izad Etemadi, Peter Fernandes, Veronica Hortiguela, George Krissa, Amy Matysio, Fiona Reid, Gregory Prest, and Steven Sutcliffe.

“I’m a major Michael Ross Albert fanboy,” joked Santalucia, who leads the company’s new play development portfolio and will direct The Bidding War. “It’s an astonishingly funny play that cuts right through to the heart of the anxieties so many of us are having, and he really met the challenge.” According to Abraham, Crow’s encouraged Albert to think as big as he wanted while writing The Bidding War, regardless of the cost involved in producing a show with a large cast.

“We’ve been interested in looking at encouraging an ecosystem where we can imagine taking Canadian work to larger stages,” said Abraham. “In order to do that, we need to practise doing it. We need to commission those plays, and we need to do more of them. We need to see how they work in this size of a venue, and then we need to be able to move on from there, and, when they’re ready, move them directly to a larger stage.”

“We don’t take it for granted,” said Santalucia. “The thing we’ve really learned and have been excited to learn in the last year is what can occur when you put a large group of people in a room — you’re talking about a really fundamentally communal, community-driven experience between the art and the public. And that’s something we’re really inspired by right now.”

Abraham and Santalucia have spent years nurturing an adventurous, loyal subscriber base for Crow’s, and across the coming season, they’re looking forward to seeing how audiences react to this buffet of new, and new-to-Toronto, work.

“Our audience will come to see what we program based on trust,” said Abraham. “We can afford to take programming risks because we know the audience is there to support us in whatever we put forward. I mean, these are goals any self-respecting theatre company should have — that’s what you should want.

“We want a sustainable future, where Toronto is a theatre city, a destination,” he continued. “There is tremendous potential for that. But in order to be a big international theatre city, we have to take big swings.”

You can learn more about Crow’s Theatre here.

Comments