At Canadian Stage’s 41st annual Dream in High Park, everyone is Hamlet

Pack a picnic and get thee to the High Park Amphitheatre to watch a gripping tragedy unfold.

This summer, Canadian Stage will present Hamlet for the 41st annual Dream in High Park, which sees the company produce one of Shakespeare’s plays in the park’s outdoor amphitheatre every year. This time around, the Bard’s tale of a conflicted prince burdened with avenging his father’s death is directed by Jessica Carmichael and began previews on July 21.

“It’s not polite Shakespeare,” said Canadian Stage’s artistic director Brendan Healy in an interview. “Jessica is not afraid to get messy, and Hamlet is a messy story of murder and revenge. It really is a play about our shadow, and I think that Carmichael’s approach is one that makes space for that shadow, sees the shadow as beautiful, and sees beauty in the confrontation with our shadow.”

Healy noted that Carmichael’s interpretation of the play centres “grief and coping with grief, and trying to integrate grief and loss into one’s life: loss of a parent, but also loss of innocence, loss of youth.”

“Hamlet is transitioning into adulthood, and often loss is the thing that propels us into a new state of maturity,” said Healy. “I think the questions that Hamlet is wrestling with are questions that we all wrestle with as we’re transitioning into a new stage of life.”

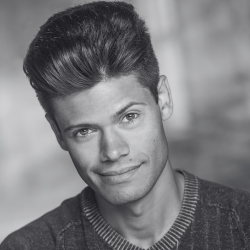

Wrestler-in-chief in this production is actor Qasim Khan, who plays Hamlet, and who theatregoers may remember from Canadian Stage’s production of the two-part gay epic The Inheritance earlier this year, or Coal Mine Theatre’s production of Hedda Gabler this spring. “Qasim’s amazing,” remarked Healy. “The Inheritance was the second time I’ve worked with him; the first was on a piece called Acha Bacha that was at Theatre Passe Muraille [in 2018], written by Bilal Baig. Like all great actors, Qasim contains multitudes, and is able to embody complex psychologies in very truthful ways. Hamlet is such a complex character who is navigating massive questions. I think Qasim has the intelligence but also the heart to really dive into those questions. He has all the qualities that an actor needs to have to carry a show.”

Khan is one gem in a jewel-box of an ensemble that includes Raquel Duffy (Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead, Neptune/Mirvish) as Gertrude, Diego Matamoros (A Public Reading of an Unproduced Screenplay about the Death of Walt Disney, Outside the March, Soulpepper) as Claudius, Dan Mousseau (Prodigal, Howland Company, Crow’s) as Laertes, and Stephen Jackman-Torkoff (The Inheritance) as Horatio. “The list of actors in this play is extraordinary,” said Healy. “Audiences will be in such good hands.”

Although the title role is Khan’s, on Canadian Stage’s website all the actors are billed as both their individual roles and as Hamlet. Theatregoers curious about the reason for this will have to see the production, though Healy provided a clue. “My understanding [of Carmichael’s interpretation] is that we’re all Hamlets at moments in our lives” he said.

Ever since Guy Sprung first staged A Midsummer Night’s Dream in Toronto’s largest park in 1983, the tradition of outdoor Shakespeare in High Park has been going strong — the tradition celebrated its 40th anniversary last year. Healy first experienced Dream in High Park as an audience member when he moved to Toronto almost 25 years ago. “I went to see A Midsummer Night’s Dream directed by Ahdri Zhina Mandiela,” recounted Healy. “It was kind of a hip-hop Midsummer Night’s Dream. There was a circus performer in it, [acrobat and multidisciplinary artist Colin Heath as Puck], and it was a fun, contemporary take on that story that kind of blew my mind, and that felt really reflective of this city.”

For Healy, Dream in High Park mirrors Toronto not only onstage but in the audience as well. “It’s Canadian Stage’s most diverse audience,” he said. “It’s people from all parts of the city, all walks of life, all backgrounds, all generations, and it’s a big audience: we can get eight or nine hundred people up on the hill nightly.

“There’s something really democratic about outdoor theatre,” Healy continued. “[Indoor] theatre spaces are awesome, but they can sometimes be intimidating and limited. For many people, [Dream in High Park] is their one trip to the theatre that they do every year. For many young people, it’s their first experience of theatre.”

Why is that first experience so often a play by Mr. William Shakespeare? “So many of Shakespeare’s stories have a kind of elemental, foundational quality,” said Healy. “They just hit some of our most basic primal emotions of survival and sadness and joy. It may sound corny, but there’s a kind of timelessness to Shakespeare, because his sources are so deep. The story of Hamlet is an ancient story. It’s based on a myth that existed long before Shakespeare,” he said, referring to a Norse legend first recorded by Danish historian Saxo Grammaticus around 1200 AD.

Shakespeare and the outdoors make a perfect pairing. For one thing, Shakespeare “was [often] writing for an outdoor setting” such as the original Globe theatre in London, said Healy. (The first performance of Hamlet was even more open-air: it likely took place on a merchant ship off the coast of Sierra Leone in 1607.) The logic of Shakespeare in the park goes beyond a performance tradition, however. “The elements are so present in Shakespeare’s work,” Healy continued. “Nature is a major theme and energy in his plays, and a constant force that humans are dealing with, either being driven by or fighting against. When you experience a Shakespeare play outdoors, you’re just so aware of the elements of nature, that it makes the text sparkle. People can actually call the heavens and do all those things.”

The outdoor setting also heightens the passage of time in Shakespeare. “It’s really special to start a show in daylight, then end the show in twilight,” Healey said — a transition that feels fitting for Hamlet’s descent into tragedy.

Speaking of time — “It’s only 90 minutes!,” Healy added.

“Typically, Hamlet is like a three-and-a-half hour play. Carmichael has done a brilliant edit to the script, and the story gets told beautifully. One thing about an outdoor setting is that you can only sit in a park for so long: 90 minutes is just right. I think it [also] takes away the intimidation factor of three-and-a-half hours of Elizabethan English.”

Toronto is no stranger to condensed versions of Hamlet, and different cuts or adaptations of the play draw out different facets of this complex tragedy for audiences to savour. This past May, Raoul Bhaneja embodied seventeen of the play’s characters in Soulpepper and A Hope and Hell Theatre Company’s two-hour Hamlet (Solo). A month earlier, Guillaume Côte and Robert Lepage’s Hamlet: Prince of Denmark — also two hours — gave theatregoers a haunting, movement-based interpretation which removed dialogue altogether.

Carmichael’s take on Hamlet promises to honour the play’s profound emotional depths while foregrounding ease of engagement. “She’s built a production that I think young people will be able to follow and enjoy and get a lot out of, as well as adults,” said Healy. “Whatever age you are, you’ll be able to find yourself inside the story.”

Hamlet begins previews on July 21 and runs until September 1, at the High Park Amphitheatre. You can purchase tickets here.

Comments