Naked Men on Small Stages

I’m going to be performing in Salvatore Antonio’s newest play, S h e e t s, at Videofag, and, along with the rest of the cast, I’m going to be naked.

To be clear, I’m not worried about the size of my dick.

I’m not. It’s fine; it’s normal.

I’m at least 60 percent sure it’s normal and fine.

But the shining confidence in the normalness of my dick is being challenged by the imminent weight of an audience’s eyes, and as opening night (May 17) approaches, I’m thinking a lot about what they’re going to think, and what I’m going to be thinking when they’re thinking it, and whether or not my thoughts and anxieties about their thoughts are going to be self-fulfilling, somehow, and end up reinforcing thoughts of theirs that they might not have even thought in the first place.

I’ve gathered some of these thoughts on what it means to be a naked man on a small stage, and I invite you to read on.

* * *

Let’s start with the word stage.

We’re performing at Videofag, which is less of a theatre and of more a, um… ahh… what’s the word…? “Room!” Right: a “small room.”

Videofag is intimate, thirty seats max, and it’s a fundamentally different experience getting naked there than getting naked at Stratford. Yeah, Stratford has a bigger audience, but you’re six thousand feet away from most of them—none of them can reach out and literally grab you; there are things in the way like railings, chairs that are attached to the floor, and, you know, a stage. At Videofag, I can be doing my job: acting in the designated “acting area,” and an audience member can be doing their job: sitting in the “audience area,” and it’s entirely possible that their face will at some point be closer to my penis than my own face has ever been. (Ticket information is available at the bottom of this article.)

So, as you read on, keep in mind that the following neuroses and mind-versus-body battles will take place potentially inches away from the people in the first row, and single-digit feet away from those in the second/last row (Videofag, you will be missed).

* * *

Now let’s move on to naked men.

When naked men play characters who do sexy things onstage, they run into this lovely phenomenological problem called erections. And when I’m one of those naked men, I become very grateful that my parents live in Minnesota.

If an actor gets an erection during a sex scene, 200 percent of the audience is thinking: “Holy fuck, that actual actor has an actual erection.” Or, if the guy is soft during the sex scene, 85 percent of them are thinking: “Okay, it’s a sex scene, and the character should probably have a boner… but that actor does not have a boner—But, I mean, it’s crazy, the idea of actually getting a boner onstage… I wonder if he’s attracted to that actress…? Did Daniel Radcliffe get a boner in that one play? I wonder if I’d get a boner onstage; I think I would, actually—Oh shit, the play’s over.”

Erection or no erection, the play risks these tantalizing thoughts swimming around its audience’s mind; thoughts that are not at all helpful to the narrative. (Salvatore has, in a very smart and funny and uncomfortable way, built this whole erection kerfuffle into the narrative, and I’m very grateful that he did it with an actor who is not me. But still, I have a visible organ that is making a statement one way or another [or I’ll be sporting one of those eager but confused half chubs] that affects both the narrative of the play and the inner monologues of potentially everybody in the room, myself most of all.)

“Okay Jesse, so like four hundred people in Toronto are going to see your (probably, let’s be real) flaccid penis. No big deal, right?”

Wrong! Big Complicated Deal. A flaccid penis can mean many different—

“Jesse, sorry to interrupt, but we all know about the range of the flaccid penis; we’re all liberal and savvy and well versed in temperature-related shrinkage, and besides, you’re performing in a defunct barber shop in late May, so that probably won’t be a problem, right?”

Wrong again! It’s not just temperature, my savvy liberal friend. When I’m nervous my guts clench, and part of the clench is that all my bits and pieces tend to clam up, turtle in, regroup a few precious inches closer to my body and away from the scary, scary world, and it just so happens that one cause of this clench is, in fact, the fear of clenching, and there is no time that I am more afraid to be clenched than when I am naked on a small stage, which is, in turn, the least convenient time to be clenched given my fear.

It’s a bit of a spiral, a spiral of self-fulfilling truncation, and where does it end? Maybe my penis will recede so far into my body that it won’t be able to find its way out again. Maybe I won’t get to have sex with any (more) people in the Toronto theatre scene. Maybe I’ll escape back to Minnesota to avoid the taunts and jeers, and vow to never tell my family about the shame I brought upon them.

Or, probably, it’ll just be what it is, and people will either not care or get over it much faster than I could ever possibly conceive.

* * *

So what do these naked men on small stages really expose?

Well, people say that penises have minds of their own, but that’s not true. They are very much part of us, but they are loyal only to our subtext, our anxieties and desires, the things that we inconveniently can’t control.

I’ve gotten okay at acting calm when I’m nervous, or laughing when I’ve already heard the joke. Sometimes I get emotional when I act, but usually I don’t. For better or for worse, I’ve learned to control the outside of my body onstage to look like I’m feeling something that I’m usually not.

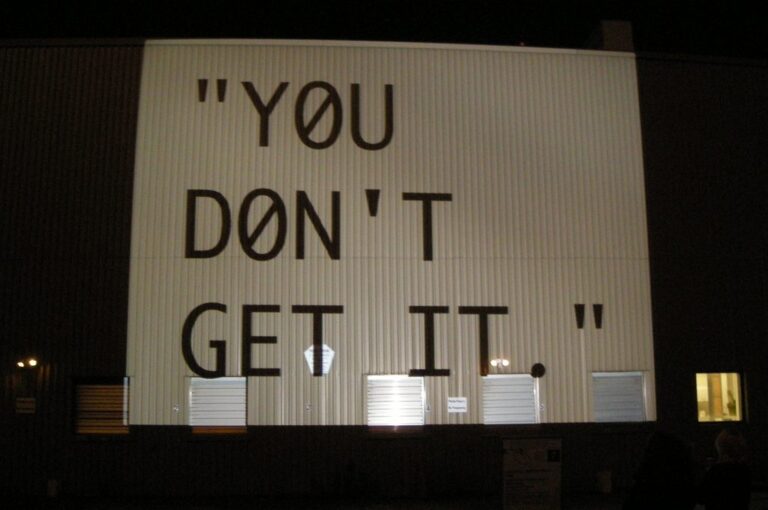

So will my penis out me as a fraud? Will it embarrass me, or reveal what I’d rather be hidden? Underneath all the obvious fears about proximity or size, maybe this is what’s frightening: that I’ve spent years learning how to act by manipulating my exterior, and now, for the first time, there’s an exposed part of me that I can’t control, that ignores my will, and whose fidelity is to my true, internal, carnal state. I’m not sure yet… Ask me in a couple weeks. But you shouldn’t come see S h e e t s (just) for the nudity, and the thrill/fear of performing naked isn’t the (only) reason why I’m doing it. Salvatore Antonio has created something vital and funny and deeply human about how we see each other and how we are seen. There’s nothing gratuitous about it. This play is about the contradictory truths we reveal only in privacy; it’s about complex passion and disappointment and hope and fury. It’s a play about the ugly and the beautiful that’s hidden behind all of our skin.

Comments