The Accidental Birth of Spontaneous Theatre

I was once asked in a radio interview, “How do you come up with an idea for a ‘hit show?’” The truth of it is, you don’t. An idea arrives, it tickles your fancy, you follow the impulse, and see where it takes you. Its success or failure isn’t really your business.

The idea for Blind Date thunked into my head in 2007, when I was invited to create a ten-minute piece for the Spiegelshow. I couldn’t tell you where it came from, but I felt it land, fully formed: a French clown, Mimi, is stood up on a blind date, so she invites a gentleman from the audience to step in. We drink wine, eat chocolates, dance… and then I see if I can get him to kiss me.

I had never done clown work before. The environment of the Spiegeltent felt like a sexy, adult circus, so I chose to do the bit “in nose.” And I quickly came to realize that the nose offered a ton of protection and permission. There’s a constant reminder to the Date, and the audience, that we’re playing: this is make-believe, I’m not going home with you after the show. It’s important. Without it, I think the show would be sort of sad, and creepy.

I did the original ten-minute version thirty to forty times that summer and was left with the question, “What if I took the time to get to know the guy?”

In my efforts to hammer out a full-length show, I slowly discovered what I was trying to do. Truth became an integral part of spontaneous theatre long before we even had a name for what we were doing. The audience member–turned-Date demanded it. They seemed to be able to smell it if I ever tried to make anything up. I’m just not a good enough actor to look into a civilian’s eyes and lie to them. And it seemed a fair exchange, as I started asking them very early on to just be themselves and to not make anything up. Telling the truth takes the pressure off either of us to come up with something “interesting,” and truth is always so much more interesting than fiction.

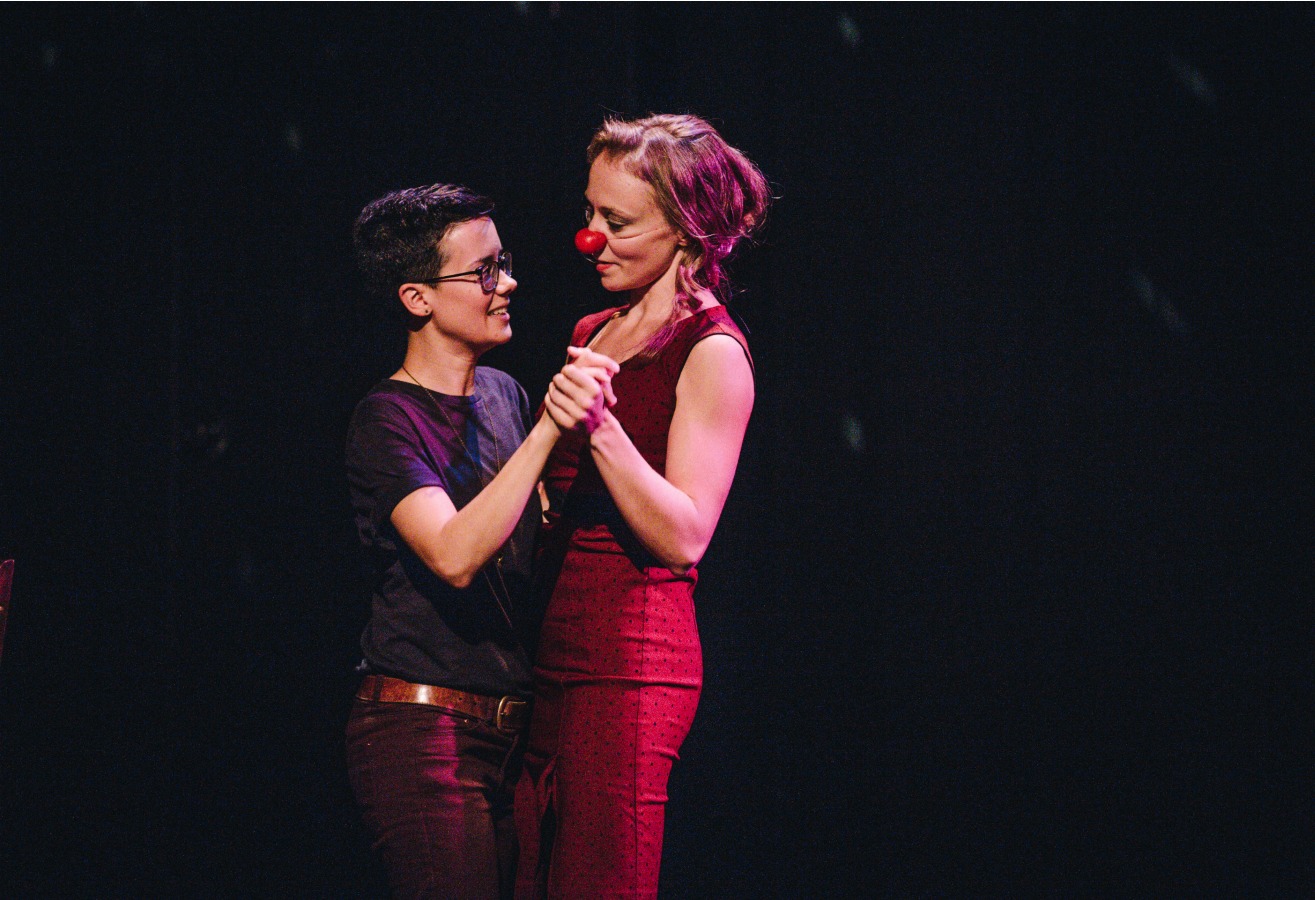

Rebecca Northan in Blind Date. Photo by Michael Meehan.

The first night we played Blind Date, there were twenty-eight people in the audience. The size of the house doubled every night until the run was sold out. I think audiences were responding to the truth and the danger.

Somewhere along the line, an audience member suggested we come up with a name for this style of theatre, so that we might write about it, teach it, share it, claim it, and be able to create more shows in the genre…. “Spontaneous theatre” seemed like a good way to represent the improvisation and the structure in one. Both halves of my artistic self are equally weighted in the name: “spontaneous” for my improv background and “theatre” for my training in mainstream, scripted shows. Spontaneous theatre is defined by a repeatable narrative structure, with an audience member in the lead role introducing uncontrolled variables. I suppose on one hand that it’s not too dissimilar to Commedia, where actors improvise based on stock characters and simple narratives. The addition of an audience member, a civilian, ups the danger quotient for me, as well as heightening audience engagement.

Every time we’ve done a Q&A, I’ve been asked, “Do you ever pick a woman?” My answer has always been no, because I’m not gay, and I want the show to be infused with as much truth as possible. One of the other women who does Blind Date, Julie Orton, is a lesbian. During our US/Canadian tour, I asked her to play the show “straight,” because that’s what we’d sold to presenters. She and I talked at length about how the lie about her sexuality, in a show otherwise steeped in truth, hurt her soul a little bit each night. By the time we got to Tarragon in 2015 and the question came up again, I thought, “Enough is enough!” and I tweeted to Buddies, “How about Queer Blind Date?”

Spontaneous theatre has evolved over the years. Early on, I was asked to pitch a show that built on what I’d learned doing Blind Date, which resulted in Legend Has It, a fantasy adventure where an audience member becomes the story’s hero. And I’ve kept pitching. Since then, whenever a new idea pops into my head, I fire off a few emails to see if there’s any interest. Sometimes there is, sometimes there isn’t. I tend to yo-yo between insufferable arrogance and crippling self-doubt. When I’m up, I pitch. When I’m down, I berate myself for thinking that anyone would even be interested. Occasionally I get a “yes,” then I crumble over having to follow through. But I’m finding the more I push into this unknown field of spontaneous theatre, the more a picture is forming. I’m starting to get a feel for this thing that seems to want to come through.

My improv teacher, Keith Johnstone, has always said, “It’s the job of the improviser to simply take the next most obvious step based on where you’ve been.” Nine years, 450+ performances, four other “Mimi’s” and a “Mathieu” later, here I am looking back on the birth of spontaneous theatre and Blind Date. It only makes sense to keep opening, opening, opening these shows, and the genre, up for more love. So when it comes to spontaneous theatre, I’m very happy to keep going.

Comments