Disability, Represented

It is rare to see a cast comprised of disabled actors onstage telling their own stories.

As an actor living with a disability—I’m a bilateral arm amputee—I’ve worked on productions with a mix of able-bodied and disabled actors. But now, for the first time, I will be performing with a full cast of actors with varying forms of disability in RARE Theatre’s After the Blackout.

This realization gave me pause. Why is it that I have had little experience working with other actors with disabilities? Why is there such a lack of representation when it comes to the stage and screen?

We applaud and award actors for their ability to transform and take on the characteristics of persons with disabilities, like Eddie Redmayne’s Oscar-winning portrayal of the late Dr. Stephen Hawking. I cannot deny being moved by some of those performances, but that doesn’t minimize the reality of appropriation.

One may argue that being an actor means the opportunity to become a chameleon, capable of playing a wide array of characters with true authenticity. Fine. However, there is a serious issue when the stories told about disabled people are, for the most part, written and played by non-disabled people. It leaves those of us with the lived experience feeling voiceless and unappreciated. I, for one, firmly believe there is room to tell all our stories—from exploring issues surrounding disability and sexuality to the challenges of living in a society built without the disabled in mind. And, more importantly, there is an audience who wants to see them presented. So why isn’t it happening more?

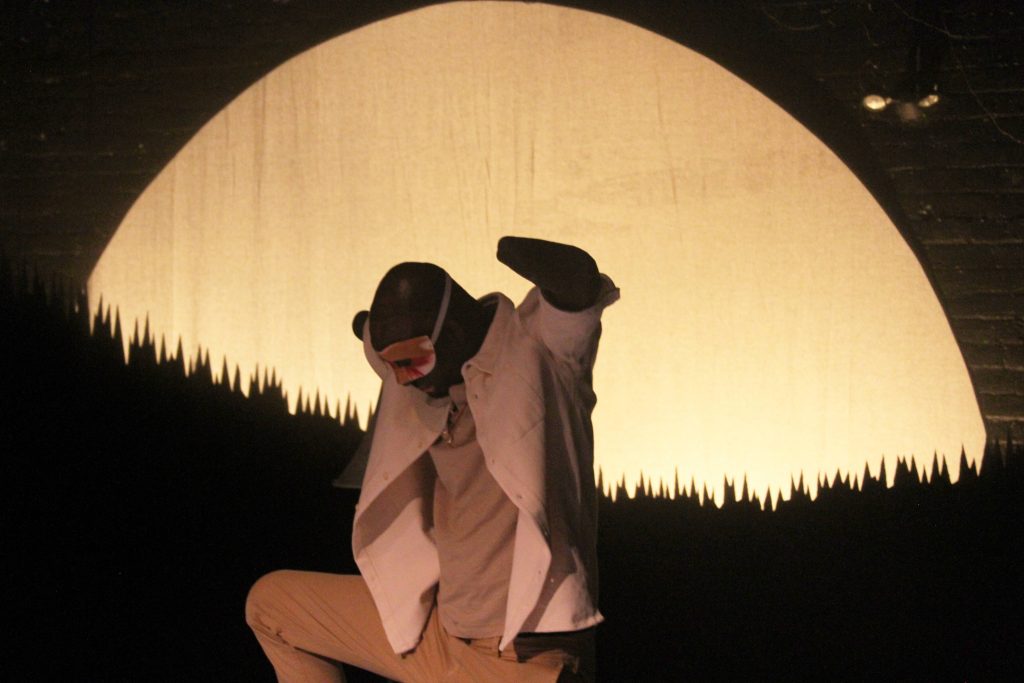

After the Blackout cast. Photo by Elias Campbell

In theatre, there seems to be more of a willingness to cast against type—though more needs to be done for diversity, of course. But compared to TV and film, the stage seems to be ahead by leaps and bounds. Perhaps because when art is run primarily as a business, as it is in TV and film, its sole objective is to make a profit. It becomes a numbers game. Anything that goes against a proven formula is seen as “too risky,” making its success uncertain.

There are some artists who are taking the risk. Last year’s This is the Point, a play that addresses misconceptions related to disability by debating questions of representation, the nature of companionship, and how people of different abilities can connect with each other on equal terms, is a good example. The play, coproduced by Ahuri Theatre and the Theatre Centre, was honest, humorous, and bold in its storytelling, and I was moved by its rawness and originality.

Audiences outside of Toronto theatre are also getting glimpses of the possibility for change, with the emergence of indie films such as Lady Bird, written, directed, and led in performance by women, and Get Out, an effective social commentary on the racial tensions of America written and directed by a black man. Then there are blockbusters like Wonder Woman and the more recent Black Panther. All of these films were artistically and financially successful, so it can be done, but it is clear that while we’re making advancements in some areas, we’re still quite behind in others, such as disability.

As a kid, I was aware that there weren’t many actors of color in leading roles in the movies. I can imagine myself as a black youth finally getting to see a black superhero on such a grand scale, portraying such strength and pride, embracing blackness and African culture. I can imagine the effect it would have had on me, how it would have inspired me and instilled me with confidence. And since I lost my forearms in an apartment fire in 2012, I have become aware of the lack of representation of differently abled individuals on the stage and screen. I have realized how important it is for marginalized communities to see their stories represented, because it indeed influences attitudes and behaviours. To echo Paul Sun-Hyung Lee at the Canadian Screen Awards, “When you give people a voice, other people start listening, things start to change—and we need change.”

We need to give those who have limited liberties a platform from which they can have their voices heard. Theatre, movies, and TV should never make others feel isolated because of gender, race, sexuality, or mental and physical abilities. It is no longer acceptable or excusable to exclude artists based on their physical or mental disabilities. It is no longer acceptable or excusable to cast an able-bodied actor to play a character who is blind, deaf, or missing a limb when there are actors who identify as disabled waiting in the wings. We no longer hire white actors to play black characters—why is this any different? I hope, one day soon, we will be watching artists with disabilities tell their stories more frequently on stage and screen.

Comments