The Scientist and the Artist: Conversations with Eugenia Kumacheva and Fiona Reid

Between them they share countless top honours in their respective fields of the performing arts and science, testaments to the depth and longevity of their careers. Although having grown up around the world, they each now have families of their own here in Toronto. Ultimately, they’ve exceeded the expectations of their younger selves. And yet their curiosity and determination have far from waned.

In a sense, they’re just getting started.

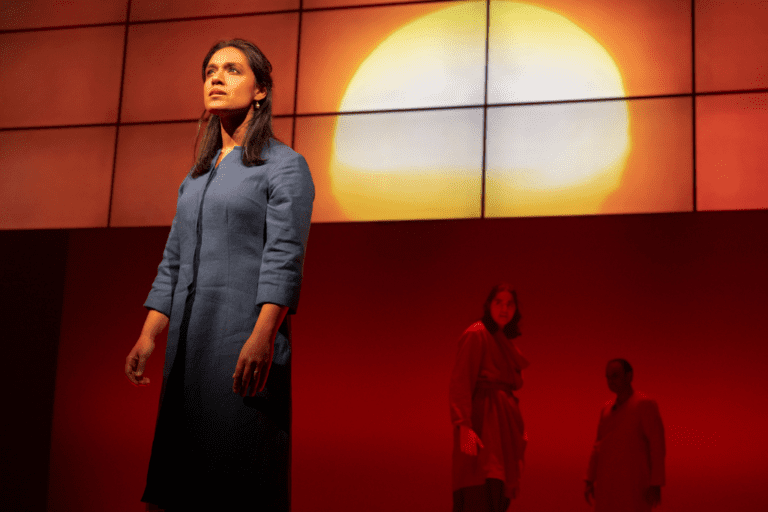

Lauded actor, Fiona Reid, currently stars in the Canadian premiere of Lucy Kirkwood’s The Children at Canadian Stage (a co-production with Montreal’s Centaur Theatre). With critically acclaimed productions at the Royal Court Theatre in London, England and on Broadway, the eco-thriller is set in the aftermath of a nuclear disaster and follows the reunion of two retired scientists and their former colleague (played by Reid). While the life of a scientist may seem in opposition to Reid’s own, there are numerous overlaps as attested by the equally accomplished, Dr. Eugenia Kumacheva, a polymer and materials scientist. These women have faced surprisingly similar obstacles over the course of their seemingly different careers.

***

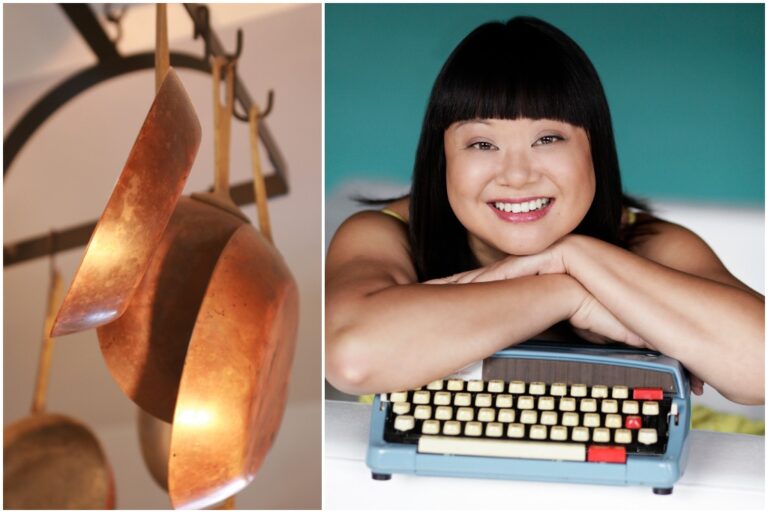

Reid has been a mainstay of the Canadian film and theatre industries for over forty years. With tenures at both the Stratford and Shaw Festivals and credits from regional theatres across the country, she has tackled theatre’s greatest roles. She is the recipient of the Toronto Life Women of Distinction Award, an honorary doctorate from Bishop’s University and a member of the Order of Canada since 2006. However, she insists her eagerness outweighed her talent at the start of her career. She immersed herself in theatre while an undergraduate student in drama at McGill University thanks to the shared enthusiasm of a female classmate and took endless classes after graduation. (Yes, she auditioned, but, no, she was not admitted into the National Theatre School of Canada.) “I mean this could be a message of hope.” Reid says, commenting on her lack of professional success as a young adult.

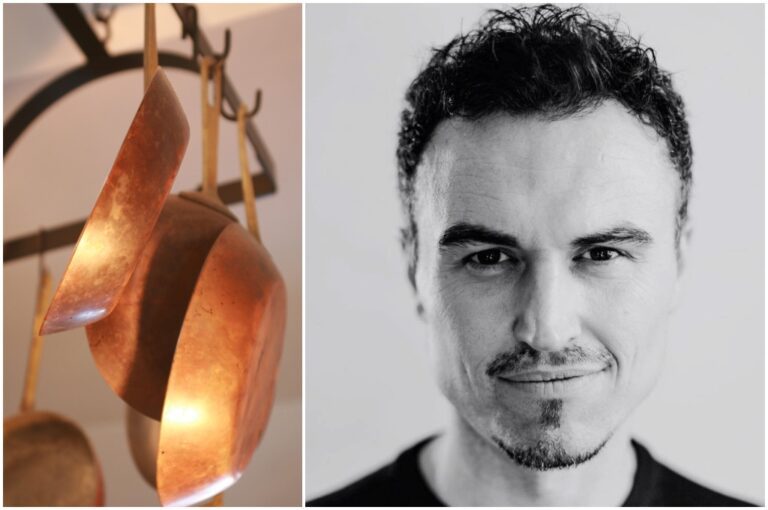

Meanwhile University of Toronto Professor of Chemistry and Canadian Research Chair, Eugenia Kumacheva, originally also had her sights set on a career in the arts. An avid amateur poet born and raised in Odessa, Ukraine, she hoped to become a journalist. But an inspirational high school chemistry teacher and the stability offered by a career in science shifted her goals. Finishing in the top percentile of her class, she committed to the idea of a life in research at the end of her undergrad at the Technical University in St. Petersburg. Kumacheva jokes: “My friends ask me now, ‘Where’s your poetry?” and I say, ‘My poetry is in my proposals.’ I bring this part of me in when I’m trying to receive funding.”

After her studies in Montreal, Reid returned to Toronto, where she had spent her high school years, to begin her career as an actor. “You didn’t have to have a second job when I started. I mean, I did. It’s just so much more difficult to have a career in theatre in this country [now].” Despite booking a series lead, Cathy King, in the CBC sitcom, King of Kensington, soon after her arrival in Toronto, Reid was scared of failure at the time. “And it has not shifted,” she adds. “Acting’s not something you achieve, it’s something you grow into and continue to journey through.”

My poetry is in my proposals.

Until she was accepted into the PhD program at the Russian Academy of Sciences, Kumacheva was similarly fearful in the early stages of her career, asking herself, “Where will I land?” By way of working as a staff scientist at the Moscow State University and then a postdoctoral fellowship at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel, she landed in Canada with a two-year temporary position in a research group in the Department of Chemistry at the University of Toronto. Although the position was outside her area of research, toward its end she came upon an opening in her exact field in the very department she had been working in. “It was like a position that was made for me.” She only had one week to prepare her application and articulate, for the first time, what research she would hope to lead. “I was always doing research under somebody, but to become a professor? It was never on my list.” Despite offers from American universities, Canada is comfortable and, for her, the ideal middle ground between Europe and the US in its values. “The relationships between people are cleaner. People have to have some ethics, and culture, and human attitude towards each other.”

Strong in her own morals, Kumacheva asserts that she has never faced any gender discrimination during her career. “There were other issues, but not because I was a woman.” She was the first Canadian to win the L’Oréal-UNESCO Women in Science Award in 2008. In 2017 she became the first woman to win Canada’s top award in chemistry, since its founding in the 1950s, the CIC Medal. Now a jury member for the Women in Science Award, Kumacheva connects with up-and-coming and established female scientists from around the world on a regular basis. She cites colleagues in Japan and South Africa who have overcome incredible difficulties in order to rise to the top of their respective fields. “When I compare my career with theirs, I cannot blame anybody.” From her experience on hiring and scholarship committees, she insists that no matter an individual’s gender, they must be assessed on their accomplishments. Referring back to her acceptance speech for the Women in Science Award, she says “There is no women’s science. There are women in science.”

For Reid though, in an industry where casting is too often specific to gender, discrimination is a constant. “Are there ever enough parts for women? No! No. There never have been. Thank you, Mr. Shakespeare.” She notes the absence of roles for older women. “Just when you go, ‘Oh, I kind of think I know what I’m doing now.’ You feel like, ‘Oh! Am I supposed to disappear? I didn’t get that memo.’”

Am I supposed to disappear?

Yet Reid is aware of the opportunities she has been afforded as a result of her ethnicity: “One has become aware recently that as a white person one has enjoyed a certain paucity of vision on the part of certain directors to not be as inclusive as they needed to be. It should have started years ago. We have lagged so far behind other English-speaking countries in terms of inclusivity.”

She credits the incoming generation of artists for humbling her and teaching her—particularly when it comes to these politics. “I thought I was liberated. [But] I get stuff wrong in terms of inclusivity, in terms of gender issues.” Reid feels a responsibility to this generation, but not necessarily to enforce her process on them. “Some of them don’t want to learn what I have to offer. And I have to respect that.” Self-admittedly “slavish” in her respect to playwrights, Reid notes an increasing freedom in an actor’s interpretation of dramatic texts in recent years.

Beyond theatre, Reid feels a greater responsibility to younger generations on behalf of her own: “My generation had so much given to us: so much luck, so much good fortune. And essentially my generation has squandered their responsibility in so many ways to the younger generation. We took the money and we ran with it.”

There is no women’s science. There are women in science.

Kumacheva feels this responsibility in her relationship to her students, who she sees as (younger) colleagues. She prides herself on her connection to them. “I think that I make the biggest impact when talking to my students. Some of them tell me, ‘If not for you, I wouldn’t have started my career in science.’ I’m better when we’re in my office, when they’re asking me questions and when I help them to deal with different situations in research, in relations with people and in raising money.” Like Reid, Kumacheva doesn’t aim to enforce her ideas on her young colleagues, but rather ensure that she is available to them when they reach out for advice. Echoing her own fears from early in her career, Kumacheva explains, “My responsibility is not only for women, but mostly for young scientists: how to help them find their place in their career. Because not all of them have to go into academia and that’s fine.”

Reid and Kumacheva each have two children, members of this younger generation. Kumacheva married in her early twenties and then gave birth to both her children when the family was still based in Russia. While she was able to continue with her profession at the time thanks to support from her husband, his parents and her own, she admits that she felt guilty. “In principle, you cannot be successful in both fields. I always had this sense of guilt that I was not spending sufficient time with my children,” she says. Even during the time she set aside for family, her mind was often on her work. For Kumacheva, it was important for her children to understand that part of her belonged to them and another to her profession. She explains from her children’s perspective: “Without this, this would not be my mom.” She believes her son came to fully accept her career when he himself went on to study science at university. And where each day, he opened his textbook to the photo of a featured Canadian scientist—his mother.

Reid too speaks to feelings of guilt and remorse when it comes to raising her children. Thanks to birth control—an issue of her generation—she was able to fit it in around her career and before she felt pressure biologically. “But in terms of my kids and knowing what I did for a living and the absences—there’s no easy way around that. And anyone that tells you, ‘Your kid didn’t miss you at all. They were fine.’ They’re lying! I think. It’s just hard.” Emotions aside, she lists other challenges like the “babysitter blues,” a term for the constant search for a sitter as coined by fellow actor Nancy Palk, and not to mention then affording to pay for that sitter. “I never dealt with the guilt very well. And I still have regret. [But] regret and guilt are useless emotions. So you just have to accept them and hope there’s a part you can play to deal with them.”

Regret and guilt are useless emotions.

Assuming institutions are willing to assist with childcare, Kumacheva is confident there will be more women in science in the future. “I’m a person that likes metrics—I like to see real things instead of just talking. If a university wants to have more women in science, they shouldn’t go through a search for new faculty and say, ‘Okay, let’s take this person because she’s female.’ They have to put money into it and real support.” For Kumacheva, they need to cure those babysitter blues. “They have to give [women in science] money to hire childcare when they write proposals or go to conferences. So their brain is not thinking, ‘Okay, what is happening with my baby?” She herself remembers writing papers and preparing for exams with her children on her lap.

In the future Reid hopes for more roles for women that speak to the female experience through the ages and a woman’s eyes. She lists Shakespeare in the Ruff’s recent production, Portia’s Julius Caesar, with The Children assistant director Christine Horne in the title role as an example. In terms of her own future, she never thought she’d achieve the success that she has nor that it would be as difficult as it (still) is. “Now it’s about trying to have some kind of agency in my career—I’m not ready to disappear. I still have stuff to do. I’m only sixty seven!” She sighs. “I mean you do go, ‘Am I being retired?!’ It just makes me mad. Could I just be sixty-seven? Or do I just have to play fifty or seventy-five?” It’s taken Reid a lifetime to learn the resilience necessary to persevere in the industry. And it’s what motivates her now more than ever.

Since Kumacheva started her career, materials science has evolved dramatically. The future is equally exciting for her. At the moment, her research centres on the development of a jello-like substance known as hydro gel in which model cancer tumours can be kept alive outside of the human body. Using the hydro gel, scientists can determine what drugs the cells of the primary tumour are responsive to and administer them to cancer patients accordingly in a process known as personalized medicine. “If I can do at least ten, twenty percent of this approach, it will be huge,” says Kumacheva. From growing the cells in petri dishes to mice, ideas in this line of research that were innovative ten years ago would now never receive funding. Aside from the professional fulfilment of this research, Kumacheva is driven by the loss of her best friend to cancer, having watched her go through three cycles of chemotherapy.

Reid and Kumacheva are hopeful for the future—as uncertain and frightening as it may appear. Like the characters in The Children, they understand even this far into their careers that their actions still have an impact on their respective fields and, perhaps more importantly, on the next generation of actors and scientists. Their success—that younger generation’s—depends on leaders like Reid and Kumacheva. Thankfully, both women are wise (and humble) enough to accept such a challenge.

Fiona Reid stars in Canadian Stage and Centaur Theatre’s production of The Children at the Berkley Street Theatre from September 27 to October 21. For tickets or more information, click here

Comments