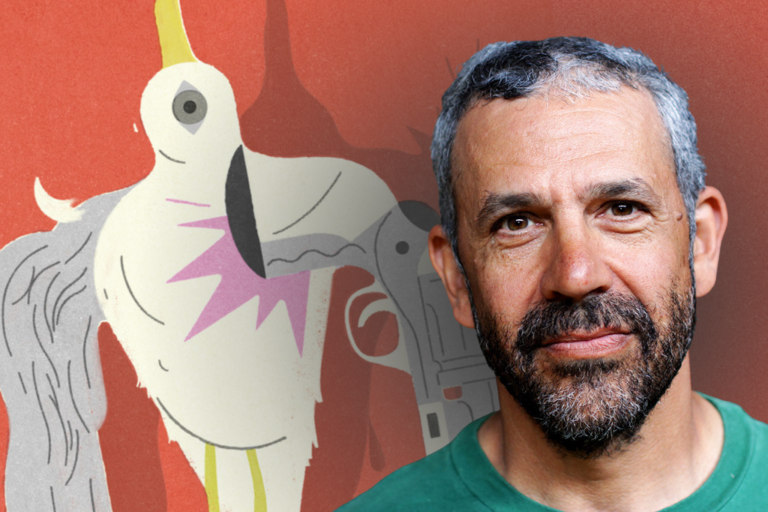

Spotlight: Walter Borden

“I am the authority on who I am,” proclaimed Walter Borden on a rainy April evening as we discussed identities and how we present ourselves to the world.

It is a proclamation that encapsulates him, the way he carries himself, and the life he has chosen to lead.

I am a new writer to Intermission and it was inevitable that I would feel nervous meeting a renowned Canadian actor, poet, and playwright on just my second assignment. But I prepared. I spent hours researching Walter’s life and filled pages of questions to draw from so I wouldn’t miss a beat and ensure that I do this man and his illustrious career justice.

But Walter is the authority on who he is. He drives our conversation and controls his personal narrative in a way that made my preparation, thorough or not, completely irrelevant. Intuitive and sharp as he is, Walter answered all of my questions without my needing to ask them and went far deeper than I would have had the courage to go.

We are sitting in the basement kitchen of Buddies in Bad Times; it couldn’t be a more peculiar setting to interview a man of this calibre. There are suits hanging on a makeshift clothesline, posters from past shows and festivals plastered on the walls, a messy shelf with a ramshackle collection of condiments, instant coffee, peanut butter, teas, and other kitchen essentials, and people milling in and out of the room.

But none of this matters because Walter Borden makes any space feel like a stage. When Walter speaks, everything else fades into the background and you can’t help but hold your breath just a little and listen intently.

On a sunny day, photographer Dahlia Katz visited Walter Borden during a break in rehearsal at St. George the Martyr, and fell deep into a meaningful chat about activism, art, and identity, full of Walter’s animated and heartfelt stories of lessons learned from his greatest mentors.

His voice is commanding and passionate, weaving in and out of forceful declarations to tender whispers, enveloping you in his story and always keeping you at the edge of your seat. He is incredibly precise too. Nothing is rushed. Everything is intentional. And absolutely no words are chosen haphazardly. He takes his time to find exactly the right word to convey his thought. Sometimes it takes a whole minute of silence, but when he finds it, it is a revelation.

Educator & Activist

To say that all the world’s a stage for Walter would be inaccurate because the truth is, all the world is his classroom. Although acting was something Walter knew deep in his bones he wanted to pursue from an early age, he is and always was, first and foremost, an educator and activist.

Over a two-hour conversation that I wish lasted even longer, Walter recounts stories from his rich life, sharing the lessons he’s learned over his years in both theatre and activism.

Walter came of age during the civil rights movement in the ’50s and ’60s, and its leaders and their teachings left an indelible mark on his being.

“During that time, I became very heavily involved with the social activist world–not just as a pastime,” said Walter. “Indeed, it became the parallel course of my life along with the artistic side, the acting side.”

Walter grew up in New Glasgow, Nova Scotia, where the seeds of his activism were already being sown. This was a town that produced a number of influential Black leaders who were, in fact, Walter’s relatives.

During our conversation, Walter would look into the distance smiling as he remembered these relatives. Relatives like Aunt Pearleen—that is, Pearleen Borden Oliver—the first Black graduate of the New Glasgow High School, who later became a social activist and historian who captured the history of Black Nova Scotians. Or even closer still, his three older brothers who were the first Black men in his community to join the Royal Canadian Air Force.

“That was when the foundation of everything was set. Everything that I became. Every philosophy that I knew,” Walter said in an interview with New Glasgow News. It was equally clear in our conversation that growing up in a strong Black community served as fertile ground for his activism.

For five years, Walter was a junior high school teacher in Nova Scotia who centred much of his teaching around civil rights and Black studies: “What I introduced to my students at the time was material on so many things that were pertinent to enlightening the appreciation of young Black students of their history, of their social responsibilities, their personal responsibilities.”

Walter also took on the role of educator beyond the formal classroom. As the communications director for the Black United Front (BUF)—a Black nationalist organization in Nova Scotia—he was responsible for publishing a monthly news magazine through which he introduced members to literature from leading civil rights activists and academics in the United States. Also, as the host of a minority affairs television program called Black Horizons, Walter used his platform to elevate Black voices.

It was not until 1967 that Walter decided to pursue acting professionally; he auditioned and was accepted into New York’s Circle in the Square.

“I realized that the theatre was going to be the stage—literally—on which I could fully realize my whole activist existence,” said Walter.

Theatre & Ancestry

His activism certainly shows in the plays that he decided to take on over his career. Walter has performed on stages all across Canada in a variety of roles, plays, and production companies, but even in his earliest days, he was always actively involved in Black theatre productions.

To note a few, he was in:

- Djanet Sears’ Harlem Duet in downtown Halifax’s Neptune Theatre.

- James Weldon Johnson’s God’s Trombones: Seven Negro Sermons in Verse at the Manitoba Theatre Centre.

- Suzan-Lori Parks’ Father Comes Home from the Wars at Toronto’s Soulpepper Theatre.

He also performed the role of Abendigo Johnson in Djanet Sears’ The Adventures of a Black Girl in Search of God, also known as the play that launched Toronto’s Black theatre company Obsidian Theatre and was later revived in Montréal’s Centaur Theatre and Ottawa’s National Arts Centre. Walter even wrote and performed an autobiographical play called the Epistle of Tightrope Time, one of the first in the history of Black Canadian literature to directly present themes around male homosexuality.

“Over the years the activist side of me has determined to no small degree precisely what I would do in theatre,” said Walter. “I always wanted to know that what I was doing on stage, how I was presenting myself on stage, was in some way advancing some aspect of my activism. That could be as dynamic as choosing to do a work that very much addressed political issues, or it might simply be doing a work that I felt very comfortable doing for no other reason than to be in a mentoring position for other young performers—particularly in the Black community.”

It’s no surprise then that his acting career would lead to his latest role as Simon Doucet in the quintessential queer Canadian play Lilies by Michel Marc Bouchard, where he plays the lead in a cast predominantly comprised of Indigenous and Black artists.

Though his casting in the play itself may not be a surprise, what may come as a surprise is that Walter’s character, Simon the incarcerated lover, is Métis. Perhaps even more surprising still is that Walter rejoices in this saying: “I don’t have to act that. That’s who I am!”

Unbeknownst to many Canadians, Walter—like many Black Nova Scotians—is of Métis ancestry.

“It was always known to my family,” said Walter. “We had relatives that lived on the reservation—my grandmother, my great grandmother. It was always known,” Walter emphasizes. “In just the same way that I traced my black ancestry, it was vital that I know the other part of me.”

That this role would present itself to Walter was no surprise to him, but rather felt like an inevitable manifestation of all the work he has done to understand and fully own his identity all of these years.

“I have been in all-Black productions and they were astounding in terms of being able to identify on so many levels,” Walter said. “The art of acting in those particular works presented a freedom that I never had in doing other theatre. And now for me to participate in a creation in which both sides of my family are creating a piece of work… It’s liberating. It’s AWE-some. It is a thing of awe.”

Identity & Canadiana

Listening to Walter talk about his identity with such unapologetic pride and joy is, in itself, awesome.

As a Filipina-Canadian woman who was born in the Philippines but grew up in Canada, I always felt like my life was this constant tug of war, an ongoing push and pull between these two places, two cultures, two identities. Living in this “in between” space within a society that reveres binaries and absolutes meant that I often had to hide and quiet parts of myself, a painful practice. And to see this man of African and Indigenous ancestry not just accept but luxuriate in all the nuances of his identity—well, in Walter’s words, it is a thing of awe.

It has taken me years to fully embrace and speak the beautiful complexities and even contradictions of my identity. To be faced with this man who feasts, who revels, who lathers in it all felt a little like dots connecting, stars aligning. I share all of these thoughts with Walter.

“You’ve crossed a threshold where you’re no longer afraid. You rejoice in who you are,” he said as he smiled knowingly.

The force and truth of his words immediately choke me up. How simple, how true they were.

“Getting to this point that you’re at means putting yourself in a vulnerable position not only with society at large, but usually with those who are closest to you within your own community,” said Walter. “They think you’re going to do yourself great damage, but more so that you’re going to bring great discomfort and upheaval unto them. But it makes no difference what they say because you understand something that they don’t understand. You understand why they want to keep you where you were. And now if only you could make them see what the enemy is doing to them—that [the enemy] once did to you, but that you’ve figured out.”

We are, of course, talking about the enemy of white supremacy and colonialism and how these forces entrench themselves so deeply within the psyches of Black, Indigenous, and People of Colour.

Walter continues: “You think, ‘I’m trying to help you set yourself free and you can’t see that because all you see right now is that I could get hurt and yes, I could. But that’s the thing—I accept it. I’d rather get hurt this way than get hurt the way you are hurting now.’ And they can’t quite see that yet. But once you get there. That’s it, there is no turning back.”

As Walter speaks, I feel instantly seen. Not because he knows me specifically, but because he knows the transformation that comes from embracing who you are in the face of systems that work so hard to rip that away from you.

We continue to veer into the deeply personal while still covering vastly universal themes. I confide in him how my passion project, Living Hyphen, an emerging magazine that uncovers the experiences of hyphenated Canadians—that is, individuals who call Canada home but who have roots in faraway places—was born precisely out of everything that he had just said. It was a threshold I had crossed that ignited a fire in me to help others see how much more painful and destructive it is to stay on that other side, to help others liberate themselves.

“There is a great contingent of people who say, ‘we can’t get anywhere until we get rid of our hyphens.’ But we can’t be Canadian until you understand my hyphen,” Walter said with the powerful force of resistance. “What you’re asking me to do is to accept Canadiana on your terms. I am African-Indigenous. And that is my Canadiana.”

Diversity & Lilies

When he says this, I begin to wonder—though I can suspect—what his thoughts are on diversity in theatre. Like every other institution and industry, it is no secret that theatre is still a largely white-dominated, white-led space. Before I can even ask my question, Walter is already in the midst of answering it.

“One thing that I find very perplexing in a lot of theatre today is that directors, producers, whatever—they don’t come to grips with how immersed they are in the very stuff that they claim they want to change. You look around and what is the preponderance of theatre that is being done? It’s still the same old stuff. That’s what’s so great about Lilies.”

Lilies is a radical reimagining of a play that takes place in French Canada but centres the voices of Indigenous, Black, and racialized people. Originally written by Bouchard and now reimagined by lemonTree creations, an equity-seeking theatre company, Lilies tells the story of two schoolboys whose love is interrupted in 1912 when one is unjustly sent to prison. Decades later, the inmates stage this story of young love in the prison chapel as the aging prisoner offers a confession to the bishop.

As Walter describes it: “The play has not changed in terms of structure and what is being said. What has changed entirely is the understanding of the words. There has been a re-understanding of the words. The playwright can write these words and they can be said by French Canadians, but we can take these same words and have them spoken by Indigenous Canadians and you’ll be getting something entirely different. Entirely different!”

In fact, this version, unlike the original, casts Indigenous and Black artists precisely to make visible the high incarceration rates of these communities, effectively demanding that new understanding of the original text. By centring Indigeneity, this version of Lilies forces its audiences to confront the effects of colonialism on our religious and penal systems in a way that did not exist in its original conception.

“If someone else takes your emotion and goes to express it—how differently it would come up,” said Walter. “Because they’d come at it from angles you never even thought about, never had to think about. And, as a matter of fact, they can take your work and do it; make you see things you never even thought you wrote in there,” Walter rejoices in the wonder of it all. “And it’s just as valid and it’s just as true. And it makes it all the richer.”

I am enthralled.

When Walter speaks, I see possibility. I see the possibility of true diversity in theatre, in the arts. I see the possibility of luxuriating in all that I am, all that we are.

When Walter speaks, I see the possibility of change.

Comments