REVIEW: Moby Dick at Plexus Polaire/Harbourfront Centre/Why Not Theatre

Pure, theatrical magic.

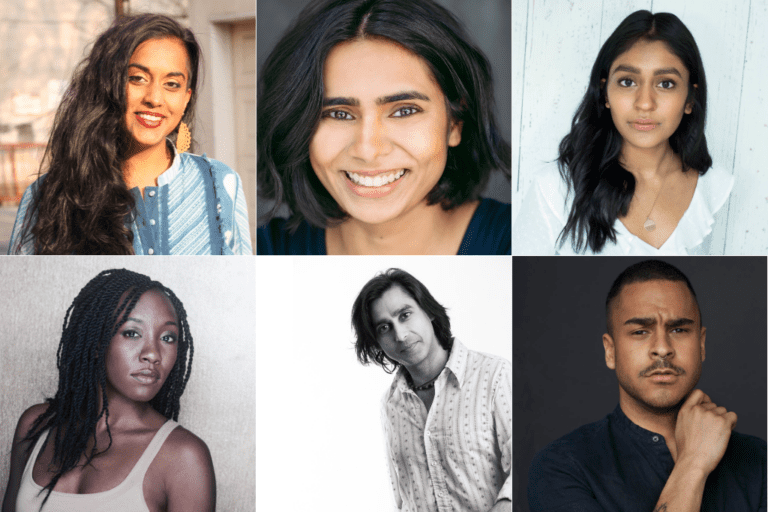

There’s really no other way to describe what I witnessed at the Harbourfront Centre’s Fleck Dance Theatre last week. The opening night, along with the entirety of the short run, was sold out — after all, it’s not every day that a show of this scale, featuring seven actors, three musicians and 50 puppets, makes its way to Toronto stages.

The sheer visual artistry of this production was unlike anything I’ve ever seen, to the point where I found myself questioning who — and what — was real. It follows the plot of Herman Melville’s book of the same name, exploring the journey of the sailors of the ship Pequod in their quest for the mythic white whale. The production, conceived by the award-winning French-Norwegian puppetry company Plexus Polaire (co-presented in Toronto with Why Not Theatre and Harbourfront Centre), uses an innovative mixture of live performers and musicians, mind-boggling puppets, and stunning projections to lead audiences through the ill-fated adventures of the obsessive captain Ahab and his crew. Director Yngvild Aspeli, along with the entire creative team and cast, has done wonders crafting a piece of theatre so intricate it truly transports the audience.

The piece uses filmic techniques to influence the audience’s eyeline and perspective, creating a 90-minute live production with all the visual interest of a feature-length film. Puppets of varied sizes create the illusion of establishing shots and long shots, and on several occasions, the puppets are maneuvered on their sides to create an aerial view of the action. While this isn’t necessarily a production that would translate to film — the combination of live bodies and puppets and the onstage musical accompaniment keep the production firmly grounded in the world of stagecraft — the film-like scenes are absolutely magical.

The show begins with a gorgeous sequence in which a school of fish swim through the ribs of a whale carcass deep underwater. It took me a few seconds to clock that the fish were puppets — their slow undulations and mixture of sustained and frenetic movements are dizzyingly lifelike. Everything else is projected, with images and videos (designed by David Lejard-Ruffet) creating a harmonious blend of technology and craftsmanship. The scene lasts several minutes, allowing the audience to take in the intricate and life-like movements of the puppets before a large tail appears ominously above the skeleton, swimming away into the depths. It’s a simple display, but it sets the tone for the entire production: this show will take its time, allowing audiences to be swept away in the detail and complexity of the characters.

Moments later, a large crowd of fisherman walk slowly onto the stage, garbed in black fisherman’s hats and coats, swaying gently as they intone as a chorus. It’s a drawn-out sequence that is entirely captivating: doubly so once you realize that less than a third of the figures on stage are people. It’s hard to tell how many of the figures onstage are real people, and how many are life-sized puppets, but as they turn in a slow circle, it becomes clear that the majority of the figures’ feet don’t quite touch the ground under their long raincoats. The realization doesn’t affect the illusion in the slightest, as the entire group sways from side-to-side, never entirely in sync, only adding to the realism of their movements.

The slow, choral chant lasts just long enough for the audience to clue into what’s happening before one of the fishermen, played by Cristina Iosif, speaks. It’s the only time one of the unnamed fishermen’s faces is visible in the production, save for the final scene — for the rest of the 85-minute show, their faces are masked or cleverly hidden by the light.

The lighting, designed by Xavier Lescat and Vincent Loubière, does wonders through the piece, keeping the puppets brightly illuminated, while the puppeteers fade almost completely into the darkness of the stage. Save for a few short moments where their exposure is intentional — a giant Ahab puppet doubles as a marionette in a scene designed to allow the audience to watch the actors maneuver his lines and limbs — I routinely forgot they were there. And the projections — the projections! — are so beautiful I could have wept. Stars and nautical maps, ocean waves and whale tails — each of Lejard-Ruffet’s video designs is a masterpiece in and of itself.

While the piece involves plenty of dialogue, it’s cleverly executed, ensuring that the effects of the puppets remain centre stage at all times. In some sequences featuring the crew, their words are barely audible, if at all, over the crashing instrumentals emulating the sounds of the sea and storms from the sides of the stage. But rather than being a frustrating experience, I found the effect to be deliberate — after all, it’s hard to imagine conversations would be clearly audible over the sounds of waves, birds, and the blowing sea air.

Throughout the production, all of the music and incredibly realistic sound effects are created onstage by musicians Georgia Wartel Collins, Emil Storløkken Åse, Lou Renaud-Bailly. The double-bass, drums, guitars, and synthesizers craft intricate sea-scapes filled with melodious whale songs, crashing waves, and the screech of far-off seagulls. The effect is magical — on opening night, it felt as though the audience was scared to breathe, as though moving too much might disrupt the transportative effect of the sound design.

After the first large-puppet sequence, the only audible audience reactions came during Ishmael’s short monologues, with short titters of laughter echoing sporadically in response to his clever wordplay. Played by Julian Spooner, Ishmael acts as the narrator of the production just as he does the book, and is the only named character played predominantly by a live actor. Later in the production, a series of puppet Ishmaels in various sizes take to the stage, often creating a filmic, split-screen effect, but for the most part, Spooner acts as the production’s human guide.

As the story progresses, there are several moments that could be described as a stall in the action. Our first spotting of the whales lasts several moments, as they slowly swim across the stage in pods, taking their time to show off the undulating flexibility of the puppets. But as with the muffled dialogue, the effect seems to be exactly what the production is going for: an opportunity to take in the beauty of the movement and the peace of the moment before the impending battle begins. The death-by-harpoon of a mother whale lasts for several moments, her body rotating in the water as the flesh peels back from her carcass before her body is eventually separated from her head, drifting slowly to the ocean floor as her calf swims anxiously alongside.

A grim sight, to be sure, but the illusion is stupendous. It’s almost too easy to forget that these are puppets, and not some grisly nature documentary playing on a screen.

For me, there were two particularly show-stopping moments in an hour-and-a-half production of show-stopping moments. The first was a sequence in which Captain Ahab obsesses over the whale, beginning with a larger-than-life puppet of the infamous captain writing at his desk. At one point, five puppeteers maneuver his limbs and body, which must measure over eight feet from peg-leg to head. As his delusion grows, more projections take over the dark stage, illuminating the blackness with nautical maps as two more Ahab puppets take to the stage in another snapshot that seems straight out of a movie or music video.

The other was a recurring scene in which the Pequod pursues the sperm whales, sending out rowboats to hunt the bleached beasts. The puppeteers took their time to show off the puppets before a burst of steam from a blowhole elicited cries of “THAR SHE BLOWS.” The boat and whales flipped on their sides, shifting the perspective of the scene into an aerial view of the action, and tiny harpoons flew across the stage, sinking into flesh. It was a magical experience that completely made me forget that the puppets in this sequence measured between one and three feet long each. Instead, it almost felt as though a camera had zoomed out to display the story from a new, exciting angle.

I’ve never seen anything like this show, and I don’t imagine I will again until Plexus Polaire returns to Canada. The combination of filmic techniques, astonishing puppetry and clever stagecraft turned Moby Dick into an unforgettable experience that I will be thinking about for a very long time. This is the art of theatre at its finest, and I must say again — it is pure magic.

Moby Dick ran for a sold-out run at Harbourfront Centre from December 13–16. For more information about the show, visit the Harbourfront Centre website.

Comments