REVIEW: Mahabharata at Why Not Theatre/Shaw Festival/Barbican

Epic in every sense of the word, Mahabharata is a two-part production based on the 4,000 year old Sanskrit poem of the same name. Produced by Toronto’s Why Not Theatre in association with London’s Barbican Centre and commissioned and presented by the Shaw Festival, the two-part production spans more than five hours in playing time, with an optional community meal and storytelling experience between the two parts.

From top to tail, this production is a stellar example of the quality that can come from taking your time. Why Not Theatre’s founding artistic director Ravi Jain first began working on this adaptation over eight years ago; he soon brought MIriam Fernandes on board as co-writer (the pair now work side by side as Why Not’s co-artistic directors). In the intervening years, Jain and Fernandes have navigated a multitude of hurdles, from ever-changing and increasingly polarizing global politics to an unpredictable and continuously evolving pandemic.

But doubtless their greatest challenge: how to transform a beloved and well-known epic from the Hindu tradition into a relevant, accessible piece of theatre for contemporary audiences in the Global North?

The answer seems to be a combination of patience, time, a multitude of generous and driven collaborators, and a desire to push the boundaries of audience expectation and experience. To me, this is more than an extra-long play: it is a cohesive experimental study of theatrical presentation which uses a multitude of techniques and styles to present a singular narrative. It’s an enthralling, visually stunning display of artistry.

As an white individual of European descent, I came into the show with no previous knowledge of the Mahabharata. Both parts of the play contain plenty of exposition to bring audience members such as myself up to speed; I felt well-educated by the production, but not pandered to.

There is nothing boring about Mahabharata. Under Jain’s direction (with Fernandes as associate director), the production soars along at a perfectly calibrated pace, allowing the audience to absorb each detail of the story before being whisked off into the next tale. Every second of the production has clearly been deliberately envisioned, crafted, and staged, and although some of the stylistic choices can seem contradictory between the two parts of the play, everything comes together in the end.

To quote the play’s Storyteller (and Jain’s program notes): “don’t be confused by plots. Within the river of stories flows infinite wisdom.”

Mahabharata: Karma (Part 1)

The Life We Inherit

Mahabharata: Karma starts simply. The stage is almost bare, with a handful of stools placed in a circle around a neat ring of what appears to be red sand on the floor (circles are a recurring symbol). Upstage sits a six-piece musical ensemble, who play their instruments unobtrusively as the audience enters the theatre. There is no backdrop, save for a single bar of lights placed just behind the musicians, creating an unpretentious playing space.

The performance starts with Fernandes, Mahabharata’s Storyteller, walking onstage — at the performance I attended, to instantaneous applause. She begins the tale of King Janamejaya, who is attempting to avenge his father’s death by snake bite by ridding the world of serpents. A few moments into her story, the lights begin to fade, and a backdrop of snake-like ropes rises from behind the band towards the ceiling.

Karma introduces the main characters of the Mahabharata, the Pandava and Kaurava clans, and the events that led to the Game of Dice that changes the course of the world. We meet Bhishma (Sukania Venugopal), the heir to the throne who takes a vow of chastity and gives up his right to rule; Pandu (Jay Emmanuel) and Dhritarashtra (Harmage Singh Kalirai), brothers prepared to take the crown and govern the land; Kunti (Ellora Patnaik) and Gandhari (Goldy Notay), their respective wives; and each couple’s sons.

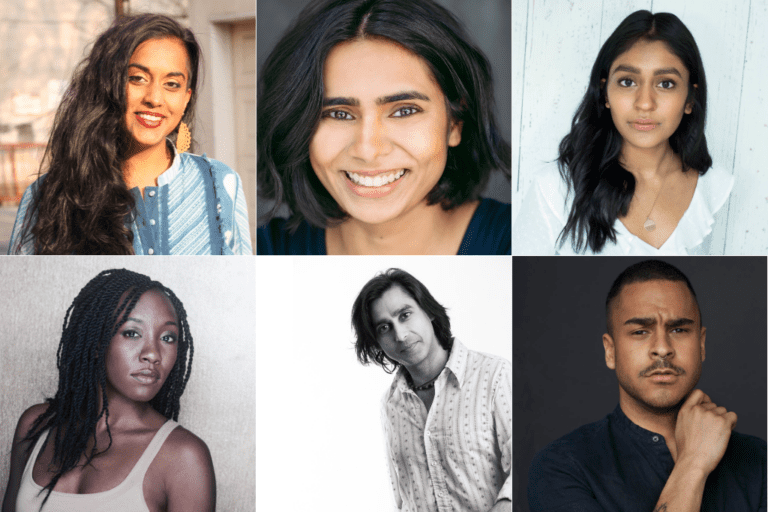

Yudhishthira (Shawn Ahmed), Bhima (Munish Sharma), and Arjuna (Anaka Maharaj-Sandhu), are three of the five Pandu boys — their twin brothers Nakula and Sahadeva do not appear in either half of the play, their plots having been cut from this condensed version of the epic. Meanwhile, the only son of the Kaurava clan to appear in the production is Duryodhana (Darren Kuppan), an appropriate choice considering the logistical and creative challenges of representing all hundred Kaurava brothers on stage at once.

Other characters appear: Shakuni (Sakuntala Ramanee), brother to Gandhari and loyal to the Kauravas; Karna (Navtej Sandhu), secret son of Kunti, sired by Surya the sun god; even the god Krishna (Neil D’Souza) plays a role in both parts of the epic. The myriad of relatives are brought to life by an ensemble of thirteen actors, many of whom take on second or even third and fourth roles to supplement the story. (Luckily there is an insert in the program, designed by Yvonne Lu Trinh and illustrated by costume designer Gillian Gallow, to help the audience keep track of who is related to whom.) The Storyteller acts as an audience guide, moving the action from scene to scene smoothly and gracefully while introducing the various characters.

It’s a simple form of storytelling that places the focus on the text and action, but I wouldn’t go so far as to call it “stripped back.” The design team has done wonders to create a versatile playing ground. Lorenzo Savoini’s set design is understated and effective: the red circle on the floor is almost a character of its own, rich with symbolism. As the story progresses and the characters begin to encounter the consequences of their actions, that circle is broken, strewn across the floor like a myriad of sunbursts. By the end of intermission, the circle is no longer a ring, but a powdery mess haphazardly covering a newly introduced red carpet. It’s a fascinating transformation to watch: order becomes chaos, and intention gives way to impact.

Circles make up an important part of the design in both parts of the play, and as the ring on the ground disintegrates, orbs begin to appear in other elements of the design. It feels like a visual rendering of the concept of karma: actions have consequences, and everything comes back around eventually.

Kevin Lamotte’s lighting design perfectly complements the set, using colours to transform the backdrop of dangling ropes into snakes hanging above a pit, green trees in a lush forest, and moonlit nightscapes. Gallow’s costumes are richly coloured and easy to move in, allowing the actors to fully explore their complex choreography. The performers add and remove pieces from their outfits for each character, occasionally changing costumes entirely, helping the audience to differentiate between characters.

For me, the focal point of Karma is the musical ensemble, comprised of Dylan Bell, Gurtej Singh Hunjan, Hasheel Lodhia, Zaheer-Abbas Janmohamed, Suba Sankaran, and conductor John Gzowski. The music, composed by Gzowski and Sankaran, is a beautiful accompaniment, perfectly timed and tuned to the tone of the piece: and just as impressive are the sound effects created by the instruments and the musicians themselves. Crackling fires and slithering serpents, a fishing net being thrown into a river — every sound is precisely calibrated. Just as the direction of this Mahabharata involves both contemporary and classical forms of storytelling, the blend of instruments represents varying cultures and traditions, from guitar and keyboard to bansuri and tabla.

The actors are onstage for the bulk of Karma, seated on the stools around the circle. As they step over the silty barrier, they become a part of the story, but even when they’re sitting outside the playing area, they’re still engaged with the action.

The production doesn’t adhere to gender-based casting; male-identified actors hop into brief roles as women, while several female-identifying and a non-binary actor take on the larger male roles. Each performer commits firmly to their characters in an impressive display of equitable casting.

There’s dynamic miming, mesmerizing dancing, impressive feats of athleticism, and most importantly, a sense of joy that radiates from the stage and into the audience. It truly feels as though every performer is having the time of their lives, whether demonstrating a mantra through meticulously choreographed movement or miming an epic shooting competition.

While the entire ensemble works harmoniously throughout Karma, Fernandes is the glue that holds it together. As the Storyteller, she is quick to guide the audience from story to story, never allowing the action to stall through the many scene transitions.

The first half of Mahabharata ends on a cliffhanger, with the promise of a battle to come. The growing tension culminates in an onstage stand-off, with the two clans facing off on the remnants of the once pristine set, ready for a fight. Jain and Fernandes picked the perfect place to end part one: Karma definitely leaves you wanting more.

Khana Community Meal

The Khana portion of the production takes place in the Shaw Festival’s Jackie Maxwell Studio Theatre between the two parts of the play on double-show days. Featuring a traditional vegetarian buffet, the meal includes a brief storytelling interlude, delivered (on the day I attended) by Fernandes and storyteller Sharada K. Eswar.

Seated at a small table on a platform in the centre of the theatre (with spectators sitting around them at shared dining tables) Fernandes and Eswar engage in a playful conversation, addressing one another as well as the audience. It’s relaxed, and almost familial, emulating the way that many who know Mahabharata initially experienced it: seated around a table, sharing a meal.

The timing of the segment didn’t entirely work out when I partook in Khana — by the time the entire audience made it through the buffet line and the storytellers took to their stage, most had finished eating — but this made the event no less enjoyable. Fernandes and Eswar have a delightful chemistry: Eswar laments Fernandes calling her an “auntie” before proceeding to make a series of groan-inducing auntie jokes.

Both performers worked from scripts, but it did not detract from their stories: the entire conversation feels like just that, a conversation between two friends. Between their banter, they dive into the meaning of dharma using tales not included in this production of Mahabharata to support their description. Though the ticket price for this segment of the show is to me a little steep at $40, I found it provided helpful context for the second part of the story.

Mahabharata: Dharma (Part 2)

The Life We Choose

Mahabharata: Dharma begins precisely where Karma ends: with the Pandava and Kaurava clans preparing for war. But where Karma leans into traditional storytelling methods, Dharma fully commits to contemporary, technology-driven staging.

Projections reign supreme, with Hana S. Kim’s digital design taking centre stage. The play opens in the beleaguered King Dhritarashtra’s war room, as the aging ruler and his loyalists work on a plan to defeat their cousins. Jain has made plenty of strong directorial choices throughout the scene — the actors sit around a table, many of their faces turned away from the audience, but the entire conversation is visible via a slightly lagging video feed projected onto screens above their heads. It’s somewhat disconcerting to witness, and I found myself focusing almost exclusively on the video; the slightly distorted, black and white footage adds an ominous aura to what was previously an enchanting, energetic story.

Similarly, the set evolves: the stage is now home to desks and chairs, computer monitors and cameras. A variety of rugs partially obscure the red sand that now covers the floor: it’s chaotic to look at, almost overwhelming, and I found myself being drawn away from the story and into the design. It quickly becomes clear that, as with the rest of the show, the distractions from the text are a deliberate choice, but in my experience this was occasionally to the detriment of the plot.

In Dharma, Fernandes’ Storyteller takes a step back from the action: this part of the story uses digital visuals to aid in scene changes and keep the story moving. The forest backdrop is now a projection of dark trees on a large screen, and the sound effects are pre-recorded — the musical ensemble is gone from the stage.

Some time into the first half of Dharma, there is a pause in the action as the play transitions into an operatic telling of the Bhagavad Gita, composed by Gzowski and Sankaran and performed beautifully in Sanskrit by singer Meher Pavri. She glides slowly across the stage, shining in yellow and gold with an elaborate, sun-like headdress, with the English translation of the lyrics projected onto a narrow screen high above the stage. This happens on top of a scene between Krishna and Arjuna, with D’Souza and Maharaj-Sandhu moving in slow motion as Pavri circles them, all set against a blinding backdrop of abstract projections. While visually spectacular, it’s a lot to take in: Even from my seat in the middle of the theatre with a clear view of the stage, I found myself unable to focus on any one element of this section for long enough to fully appreciate it, despite Pavri’s stunning performance.

As the battle began, the distraction continued, leading me to understand that chaos is one of Dharma’s central themes. There is so much happening simultaneously in every element of the design, it’s hard to figure out what to look at without missing something else. Lamotte’s lighting creates a circle on stage, mimicking Karma’s pristine ring. The Pandava and Kaurava clans are once again seated on stools, now in a line behind the round battlefield. Shiva, played by Emmanuel, takes to the stage, engaging in an intricate Kathakali dance to represent the war. Throughout the scene, Shiva is never still, which I found at times made it difficult to follow the story, as I was mesmerized by Emmanuel’s movements.

The only battles unobstructed by Shiva’s dance are those between Karna and Arjuna, as they finally settle who is the superior warrior, and Bhima’s defeat of Duryodhana. The latter fight actually features weapons, a first in the production. The conflicts are short but tight, finally bringing a conclusion to prophecies foretold in the first half of Mahabharata.

The distraction of Shiva’s dance is a clever piece of direction: after the war, the audience is informed that the sole witness couldn’t recall the cousins’ conflicts, and instead remembered only Shiva’s feet as he danced across the battlefield. The revelation explains the directorial decision to make Emmanuel the focus of the bulk of the war scenes, but the choice would perhaps have been more effective had the audience not witnessed those two battles. But the fights themselves were well-executed and a satisfying conclusion to the building tension of the story.

After the battles end and the various characters face their respective fates, Dharma ends as Karma begins: with King Janamejaya and his quest to kill the snakes. Fernandes once again takes the helm of the storytelling, revealing the final piece of dharmic and karmic justice that affects every character in the story. The actors sit close to the forestage, illuminated by firelight, which snuffs out as their fates are revealed. It’s a full-circle ending to a cycle of strife, and to me, the perfect ending to an epic evening of theatre.

Mahabharata is a massive undertaking from a global team of artists, and as Jain noted in a recent interview with the Toronto Star, the production is primed to begin an international tour. Overall, the production presents a strong display of the artistry and diversity of Canadian theatre artists: but while Karma feels ready for the world stage, I feel that there is space to reexamine some of Dharma’s production elements to ensure that design doesn’t overwhelm the plot. In any case, the monumental production promises an exciting and unique piece of art that pushes the boundaries of style and theatrical presentation for theatregoers willing to brave its length.

Mahabharata runs at the Shaw Festival until March 26. Tickets are available here.

Comments