REVIEW: Yes, Bad Roads is hard to watch – that’s the point

Bad Roads is hard to watch. That’s the point.

Set in Donbas, a particularly scarred region of Ukraine, during the 2014 Russo-Ukrainian War, the play is an anthology of six loosely connected vignettes, each presenting the conflict from a different angle. Characters young and old, military and civilian, and victim and perpetrator are all shown in slices of life that demonstrate how the war has uprooted everything, gradually building in intensity as we move deeper into the spaces (both physical and psychological) that traditional journalism is typically unable to access.

Natal’ya Vorozhbit’s unflinching script – also the basis of her 2021 film of the same name – in Sasha Dugdale’s well-crafted English translation, aims high to demonstrate the all-too-human toll of a nation under siege. Though described as being based on personal testimonies, the play makes no claim to having engaged in verbatim theatre practice or aesthetics, opting instead to dramatize interpersonal relations between fictionalized characters. The play clearly seeks to raise consciousness about the devastating effects of the ongoing conflict, which despite being well known in broad strokes, might feel remote and abstract to the average Canadian theatregoer, especially as other armed conflicts and humanitarian crises compete for the global community’s attention.

Intermission readers might recall director Andrew Kushnir’s widely circulated and immensely thought-provoking essay about the paucity of Ukrainian stories (and the disproportionately high cultural capital afforded to Russian “classics”) in our Canadian theatre ecosystem. In it, he mentions some of his own endeavours to correct this imbalance, including curating a series of play readings by Ukrainian authors at the Stratford Festival. The event occurred this past September, with Bad Roads among its selections.

Now, as he continues to put his money where his mouth is, Kushnir brings a fully-mounted production to Toronto. It’s an appropriate choice of a piece to help fill the aforementioned dearth, since – not unlike First Métis Man of Odesa (which will be returning to Toronto in Soulpepper’s upcoming season) – Bad Roads not only promotes Ukrainian authorship, but speaks directly to the contemporary politics that Kushnir feared were at risk of being overshadowed by the steam of samovars.

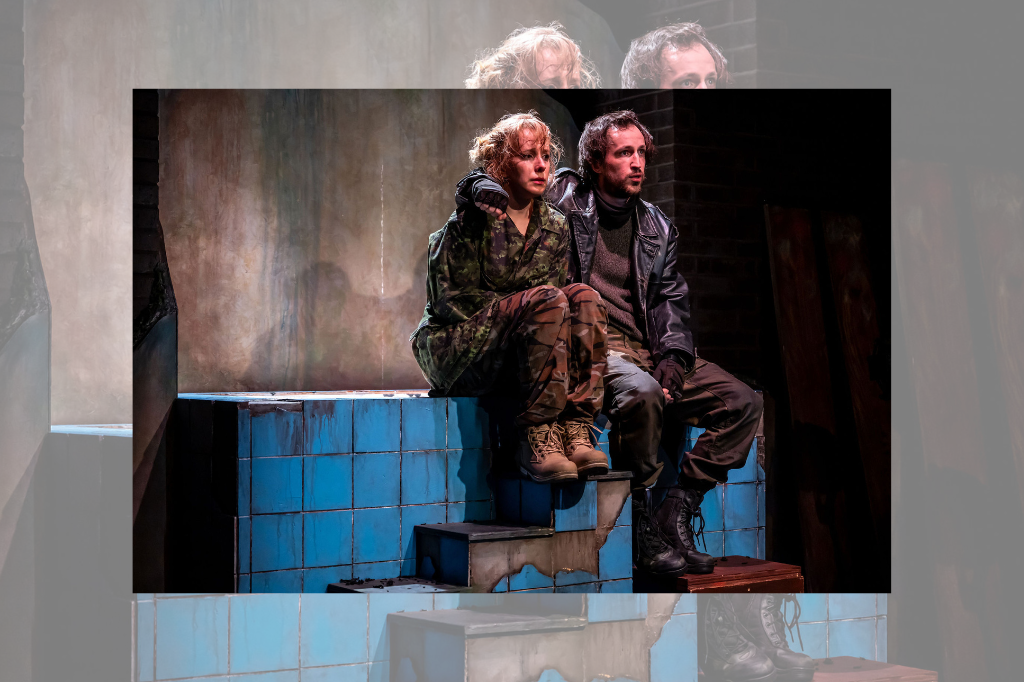

As with so much of what we’ve seen at Crow’s lately, the production is thick with theatrical haze and stacked with talented artists working at the top of their game. Sim Suzer’s bare-bones set design makes economical use of the small studio space, with a generous helping of black mulch covering the ground – perhaps leftover from Heroes of the Fourth Turning, facilitating an ease of venue turnover. The alleyway stage configuration creates a claustrophobic sense that the performers are boxed in on all sides with nowhere to go. It also establishes lines of direct eye contact among the spectators, fostering a sense of communal witnessing as we all watch each other watching the gruesome events that unfold before our eyes. Christian Horoszczak’s lighting brings about a dark and frosty atmosphere – paired with the heavy winter clothing that characterizes much of Snezana Pesic’s costuming choices – and also wrings multiple theatrical effects out of simple handheld flashlights, including one that will make you squirm (you’ll know it when you see it). The reliably excellent Thomas Ryder Payne offers a soundscape that subtly holds it all together with eerie undertones.

What elevates the piece most of all is its top-notch ensemble cast, composed entirely of well-regarded familiar faces. There is not a Slavic accent to be heard, which feels like the best way to go when everybody watching is fully aware that what they’re experiencing is a work of translation.

Michelle Monteith opens the show with the mother of all monologues, describing a love affair with a Ukrainian soldier (addressed to him in the second-person) with an impressive cocktail of heartfelt longing and wry cynicism. Though never stated outright, it is reasonable to interpret this figure as a stand-in for Vorozhbit herself, being the only character to ever acknowledge the existence of the theatre audience, making explicit reference to the act of repackaging the narrative for their consumption.

Shauna Thompson and Craig Lauzon share a truly gut-wrenching scene, presenting the play’s most ardent statement on the messiness of grief in an episode about transporting a fallen comrade’s decapitated body. Canadian theatre veterans Seana McKenna and Diego Matamoros feel a bit under-utilized in comparatively smaller and less flashy roles, but nonetheless bring their fair shares of gravitas to the proceedings without ever eclipsing their younger castmates.

But it’s the penultimate episode between Katherine Gauthier and Andrew Chown that is really going to be burned in most peoples’ memories. Depicting a young journalist being held hostage by an enemy soldier, here we see some of the most brutal realities of war brought into stark focus, requiring both actors to reach some unimaginable caverns of human cruelty. It’s a sequence that is deeply concerned with appealing to the innate humanity of not only the victims but the perpetrators as well, though the writing arguably trips over that difficult theme right as it’s approaching the finish line. The violence is handled more or less tastefully (though your mileage may certainly vary) by fight and intimacy director Anita Nittoly, evoking unsettling imagery without ever having the actors touch – a worthwhile payoff to a staging convention used throughout the entire production, established under far less dire circumstances.

It should here be noted that the content warning that accompanies the piece has doubtless been written with deliberate care, but will nonetheless strike many as being insufficient: “Bad Roads depicts forms of physical, emotional, and sexual harm as is both typical in wartime and distinct to the Ukrainian context.” For anybody who would like further details, Crow’s recommends contacting the box office before attending, something I strongly encourage people with known triggers to do prior to purchasing tickets. (A more granular warning is available for optional reading at the venue, but by that point, you’re pretty much already committed. It also neglects to mention the onstage death of an animal [thankfully facilitated by a prop] in the final episode.) There is surely a worthwhile discussion to be had about the competing forces of content and spoiler warnings, duty of care and demands of catharsis, and the desire to create safe spaces and the dangers of promising them.

All I will say on the subject is this: at the outset of the performance, the audience is told that they are welcome to leave any time they like, but also that anybody who exits the auditorium during the intermissionless two-hour performance will not be guaranteed readmission. A contradiction, no doubt; perhaps there’s another conversation to be had about the dissonance between the will of the artists and the more rigid infrastructure of front-of-house operations. However, whether intentional or not, this incongruity becomes part of the dramaturgy, and a surprisingly potent one at that.

You can leave. You might even need to leave, for the sake of your own well-being. But if you do, you won’t see what happens. You can’t see what’s happening if you choose to look away.

While watching the performance, I was reminded of something Kushnir wrote in another essay he contributed to the 2016 volume In Defence of Theatre. When discussing how spectators responded to his 2009 documentary theatre piece, The Middle Place, with comments along the lines of “you have given these people a voice,” Kushnir remarked that “what certain individuals and groups lack are not voices, but listeners – the focused and active variety – which is precisely what the theatre can supply.”

Bad Roads is ultimately a play about looking and listening. It’s about trying (and sometimes failing) to be a witness when the world refuses to offer easy answers. Even when it stumbles, even when it veers into territory that’s too viscerally upsetting to adequately behold, it’s a well-intentioned gaze into an abyss that most of us would rather not stare into – and largely have the privilege to avoid. It’s certainly not a fun night at the theatre, but if you have the stomach for it, it’s one that’s worthy of your focused, active attention.

Bad Roads, produced by Crow’s Theatre, runs at Streetcar Crowsnest until November 26. Tickets are available here.

Intermission reviews are independent and unrelated to Intermission’s partnered content. Learn more about Intermission’s partnership model here.

Comments