Want to see a magic show about race? Wait, what?

You’d be forgiven for the double-take.

It’s a fairly common reaction when I tell folks about my work as a magician. I’ve devoted my career to eschewing the standard fare of “childlike wonder” so often attributed to magic for weightier topics like catastrophic personal loss, social disconnection in an increasingly techno-reliant world and, most recently, racial inequity in this incredibly colonial inheritance we call Canadian theatre. It’s an inheritance that sometimes whispers and sometimes screams the limits of my brown Indo-Guyanese world, an inheritance that culminated in the summer of 2022, when an actor kicked me during rehearsal for a prominent Toronto production because, in their words, I was “pulling focus.”

Again, you’d be forgiven for the double-take.

That incident sent me reeling, physically and emotionally. It made me realize that the only certainty in my uncertain career as a professional theatre artist has been racism. From the audition room, to the rehearsal hall, to the tour bus, to the stage, I have always existed through the white dominance of Canadian culture. Never as myself, always through this industry’s eyes as a problem, as something to be backgrounded, sidelined, elided, tokenized, manipulated and, yes, even kicked.

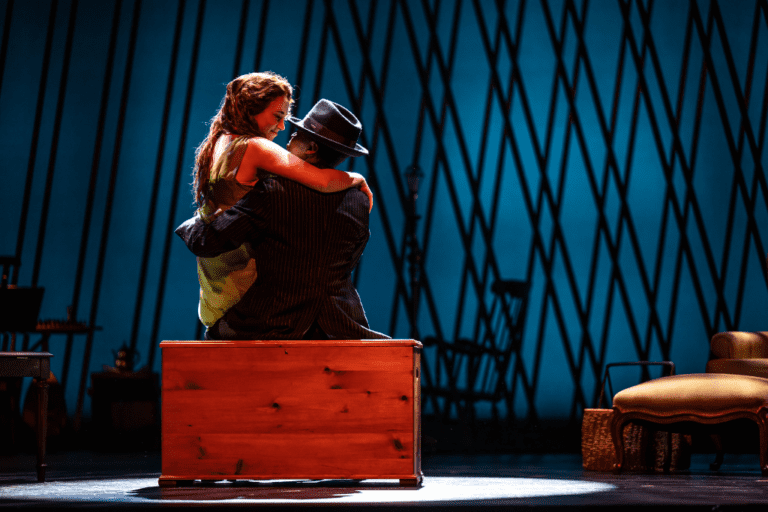

Like any artist, once the wound of that particular encounter had healed, I wrote from the scar, revealing for my audiences the systemic inequities that have burdened me as an occupant of the borderland between my brown skin and that white dominance. The show I created was aptly titled kicked in the end: a magic show, and I toured it (to great acclaim) to Fringe festivals across Canada.

Balloon animals at a funeral

Why choose an art form as entirely bereft of artistic merit as magic to address this urgent and complex topic? (It’s all right, we’re all thinking it.) It’s an institutionalized way of thinking. It’s why I can’t apply to any funding body as a magician and hope to be taken seriously. Show me the magician applicant profile on the Canada Council portal. Just show me the word “magician” anywhere on that site. To them, I might as well be asking the bereaved if they want a puppy or a giraffe.

Of course, I thankfully received OAC and Canada Council grants for kicked in the end, but I applied as a theatre artist with a show centered on a magician character. I know how to play the game.

I maintain, however, that magic is not theatre in the same way that dance is not theatre, music is not theatre, circus is not theatre, and so on. They’re all theatrical, sure. But they also each have their own unique aesthetic, technical, and relational principles that distinguish them from one another as art forms. Magic is no different. It’s held back, however, not by individual magicians, but by systems of cultural thought that dictate magic can only be one thing: Illusions done simply in the pursuit of “impossibility,” or “awe,” or that perennial “childlike wonder.”

Magic is as magic does

These systems are a function of power. The history of performance magic is the history of men performing magic. Magic is the way it is — and we commonly think of it as such — because patriarchal thinking has bequeathed a version of magic devoted to the pursuit of godlike power, the ability to dominate the natural and physical world. It isn’t a coincidence that only 10 per cent of professional magicians worldwide are women. It’s by design, whether that design means constitutionally disallowing women from joining magic fraternities until the early 90s or, more innocuously, relying so heavily on pockets that any person wearing women’s clothes is shit out of luck. In my work the actual impossibilities that represent this male power fantasy are never the focus. An impossibility is just how a magic trick concludes. It’s what we do with one another to get there that matters.

The medium of magic is the way we relate to one another as an illusion comes into being. Even if the illusion is purely visual, there’s a flow of participation that materializes in service to it. Much like a dancer moves in service of the dance, or an actor moves in service of the play, a magician moves in service of the illusion. And as the magician moves, they call out to the audience to move with them in unique psychological, physical, emotional, and affective ways. This flow of participation is the channel through which I communicate to my audience.

Pick a race, any race

In kicked in the end, intentionally performed as it was for the predominantly white audiences and performance culture of the Fringe festival circuit, I continually use these flows of participation to reveal the incredibly raced nature of Canadian society and theatre.

I need the audience to intuit the colour of my car in a photograph they’ve never seen. They must profile me to do it.

I need an audience member to form a word using scissors and a piece of paper with some letters written on it. They must cut an entirely neutral entity to shreds and then organize the remains in a pattern of their choosing for personal gain, which is all race has ever been.

Near the end of the show, I need the audience to decide which of five keys opens a lock. Up until that point the audience has always existed through my power as a magician just as I, as a brown person, have always existed through their power as a white culture. Refusing to let them be a problem for me because I have always been a problem for them, I lead by example and leave the stage entirely, never to return. They must select the correct key and end the show without me, exist for themselves in ways that I never have in this industry. Flows of participation through which I speak.

Magic’s problems are theatre’s problems

The responses to this gesture and show were beautiful and heartbreaking. I was thanked by those who felt seen and labelled a racist-against-whites by those who felt exposed. There was disappointment, elation, indignation, and anxiety. If you’ve never thought twice about magic, I don’t blame you. It’s got issues to work through.

But magic’s problems are theatre’s problems because they are all this cis-heteropatriarchal, ableist, racist society’s problems. Know that there are those of us who are trying to wield magic like theatre and any other art form worthy of the name: to address these problems by holding a mirror up to this often shitty world in the hope that we change even one mind.

Witnessing these responses firsthand has galvanized me to share kicked in the end with anyone who will listen, reinforced my desire to open their minds and yours to the truth of my place in the canon of Canadian theatre and magic’s place in the pantheon of art. Principally, these amount to the same ask: to see the world we have inherited differently. For me, a magic show about race is just the beginning. Hopefully now that doesn’t seem so strange.

Comments