There’s More Than One Way to Climb a Wall

“I think I want to try acting. Like, professionally. I’m just… I’m wondering if I can, because of my leg.”

This is the conversation I had with a drama teacher in my final year of high school. I had just seen Othello with my class at the Stratford Festival and my mind was abuzz with possibilities for my future, possibilities in this world I had just discovered. But darting around this excitement was a nagging reality: every body I had seen on stage—or on screen, for that matter—had a symmetry to it, a grace in its movement. I had neither of these qualities. My right leg is a prosthetic, specifically designed for a below-knee amputee.

I didn’t think acting was something people like me were meant to do. But I wanted it. Torn, I made a half-hearted attempt to go after my dream: I decided to audition for theatre school, but only in Montreal. By my logic, it was not far from Ottawa, where I grew up, and it has plenty of other great schools if this acting thing didn’t work out. In my final few months of high school I was accepted into the National Theatre School of Canada.

Following my acceptance, I sat down with a couple of administrators at NTS to discuss my needs as an amputee. Their question was straightforward: “Tell us what you need.”

My answer? “Not much.”

They were slightly skeptical about this response, and so was I. But I didn’t entirely know what my needs were. So I began my time at theatre school without having made any real preparations.

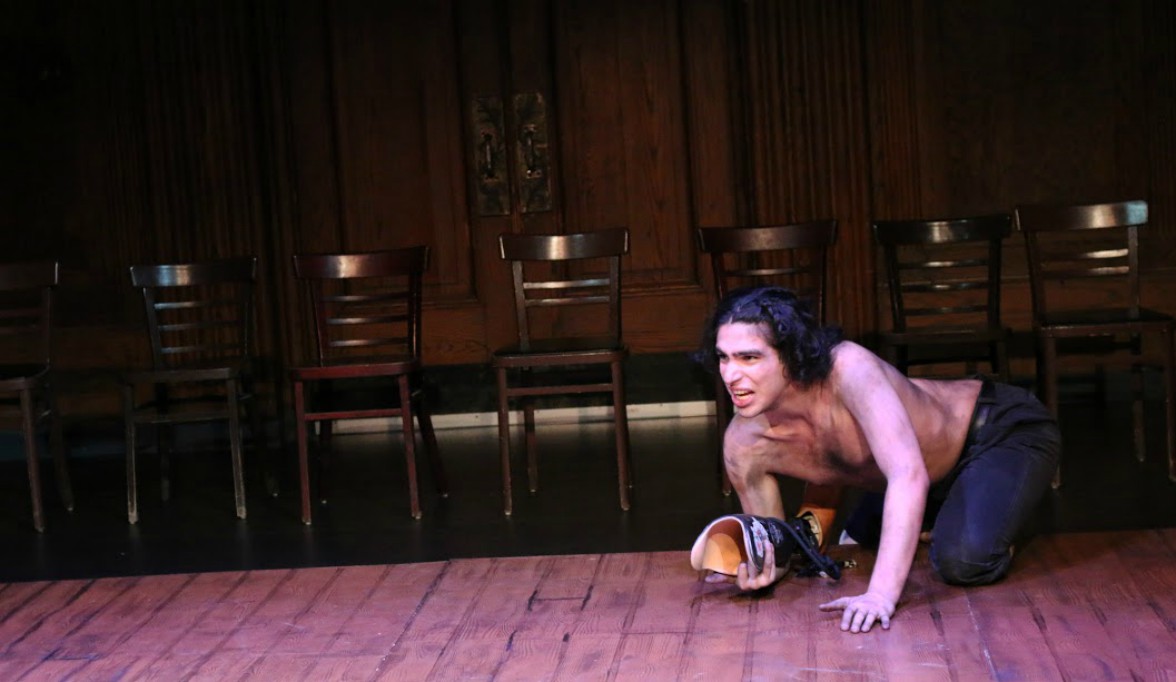

Photo by Maxime Côté

I adapted quickly to the social aspects of the school. I have always loved to use my leg as a party trick, and at NTS I put my prosthetic to good use. I’d pop it off and pretend it was a club, or I’d sit on it like a stool. Sometimes I’d even throw myself down the stairs and let it fall away—something fun to cause a freakout. When I was asked what had happened to me, I would reply with a tall tale about a serial killer or shark before kindly revealing the truth. “I was born missing a bone in my leg. So when I was a few weeks old the doctors amputated my leg below the knee.”

But during classes my prosthetic took on a different role, a kind of hurdle. In my first few movement classes, when we were told to work barefoot, I was incredibly scared of stepping on one of my classmates’ toes. I felt embarrassed and for the first few weeks would tread clumsily, keeping a short distance between me and everyone else. Eventually the frustration of literally staying behind everyone became too much, and I finally asked for help. My movement coach suggested that we have some tutorials and together we figured out ways to improve my coordination. Before long I was keeping up with my classmates.

A visible disability is likely the first thing people see and the first thing they ask about. Nearly every director I have worked with has asked me questions like, “Can you jump?” and “How about run?” Every time, I have responded with, “Tell me what you need me to do. Direct me. If I can’t do what you want I’ll tell you and then we can figure it out.” (Also: I can run and jump, yes.)

This became the unwitting theme of my working life, both inside and outside of NTS: “Let me tell you when I need an adjustment.” Whether it was changing how I walked up stairs on set, because the ones we had were too small for my prosthetic foot to climb on, or needing thicker pants, because the ones I was given were too thin and would get shredded by the hard plastic edges of my prosthetic during a fight scene, there was always something that needed to change to allow me more freedom on stage.

A visible disability is likely the first thing people see and the first thing they ask about.

In my second year, my classmates and I were preparing for a production of King Lear. When the casting was announced, I found myself faced with Edgar, the son of Gloucester, a hero of sorts. Early in the play, Edgar has to flee for his life, and he disguises himself as a madman/beggar named Poor Tom by stripping off his clothes. A few days before rehearsal began, my director came up to me and said, “Yousef, I want you to think about how you plan on handling Edgar’s transformation into Poor Tom.”

My first response to this was, “Oh, his nudity? Well the costume designer told me you wanted me in my underwear and I’m cool with that.”

“… Well, yes… but I just want to let you know that Edgar is a character you can play around a lot with. What’s important for Edgar is his transformation, so you should focus on that. Think on it and get back to me.”

So I had a quick think. I don’t know where this idea came from, or why it stuck itself in my mind, but the next day I approached my director and said, “I want to take off my prosthetic.”

He paused for a moment considering what I offered. I could tell he was intrigued and he pressed me for details. “Okay, that’s a good idea. Would you like to use crutches? A cane? A stick?”

“I want to crawl on the ground.”

He was enthusiastic about this. “Okay! Let’s give that a try.”

And so began a process I hadn’t considered before. I wasn’t working with my prosthetic as an afterthought—instead, it informed my work. Edgar’s title and wealth were no longer the only things that defined him, his physical identity was also in play. I wish I could say it was freeing from the beginning, but, like all big shifts, I was plagued with fear and doubt. What if the audience became uncomfortable, and not in a good way? What if this was a bad idea? Was I just a plain-old bad actor, using my leg as a proverbial and physical crutch?

Yousef, right, as Edgar in King Lear. Photo by Maxime Côté

As I dug into Edgar, I found an unpredictable side to him, as well as reason for my instinct to crawl on the cold wood tiles: Edgar learns of the plot against him while disguised as Poor Tom, and he also saves his father’s life while disguised. By stripping himself of everything that defines him, his leg along with his title, he reveals what he is truly capable of. Physically, onstage, I was at first limited in my movement. I clumsily used all my limbs to propel myself across the floor. But as rehearsals went on, I became more graceful. I was eventually able to use the unusual nature of my physicality to frighten my scene partners and support Edgar’s disguise. My approach to movement became unconventional. At one point in the script, Edgar is supposed to run off stage. But, being on my hands and knees, that wasn’t possible. I had to find another way to make a speedy getaway without my prosthetic, which turned out to be rising on my one leg and hopping really fast to make my exit.

I am not one for the idea that you can do anything you put your mind to; as far as I am concerned that feels too much like blissful ignorance. But beyond the obvious and extreme examples—say, me leaping ten feet in the air with no sort of mechanical assistance or training—I can’t list what I’m unable to do off the top of my head. No one can easily come up with a list of what they can’t do. People don’t want to focus on their limitations, and adaptation is always possible. If there is a wall, there is more than one way to climb it.

This concept came to the forefront of my consciousness during my performance as Edgar, and, rather than fade, grew as I began to seek out other artists with disabilities and was exposed to unconventional projects and performers.

Yousef as Edgar in King Lear. Photo by Maxime Côté

Yousef as Edgar in King Lear. Photo by Maxime Côté

I have seen performers of all different abilities create beautiful shapes dancing in wheelchairs and with other assistive devices. I have come across pictures of Prince Amponsah with a sword as a prosthetic arm; watched Jack Volpe perform a gut busting-stand up set in ASL. The commonality between these artists’ adjustments is their simplicity, which allowed each individual to focus on the story they were telling as opposed to struggle through movement or text.

It’s important for us to be given the space to consider the challenges of each performance before we begin. Sometimes all we need is a moment. A second to think, weigh the options. I recently got to try something entirely new in my practice. I performed a short piece with the spectacular Erin Ball, a double-leg amputee and circus artist specializing in aerial silks. She shared her knowledge with me, and together we took the time to experiment in rehearsal and developed a piece that ended with us firing confetti canons we had attached to our prosthetic legs.

Yousef with Erin Ball

No two bodies are the same, and adaptation can take many forms. The nature of it forces us to make bold choices onstage, keeping both audiences and ourselves engaged. Contrary to what some people think, people with disabilities are not a burden. Our voice is just as important, our bodies just as capable, our minds just as sharp. The way we work is radical, and the theatre is supposed to be a radical space.

After all my time at NTS, I still think about the response I got from my high school teacher, when I told him I wanted to act professionally.

“Yousef, you can act. The thing that should matter is the quality of your work. If you ever play Hamlet, you will be a Hamlet who happens to have one leg. And that doesn’t matter because you will never literally become Hamlet, no one does. Your job is to tell the story, so focus on that and you will succeed.”

Comments