Remember to Breathe

Standing, feet hip-width apart, I gently released the base of my skull forward off the top of my spine, curling my chin down and under. As the top of my head slowly descended toward the floor, a powerful wave of heat rushed through me and my whole body shook as a massive lump arrived in my throat. I was doing my first spinal roll-down in my first voice class in the grad program at York University. Despite the fact that I had gleefully signed up to do an MFA in Acting as well as a diploma in Voice & Speech, in that moment I wanted to run screaming out of the studio, never to return. It was that or kick the shit out of something. Instead, as I glided downward through my thoracic vertebrae, I suddenly froze in fear and choked back tears as my teacher asked me what I was noticing. I expressed terror at rolling through my lumbar spine, where I’d had a discectomy less than two years before. He gently urged me on, guiding me to “skip” the lumbar vertebrae that had undergone surgery, until I was hanging forward at the hip sockets, the top of my head just a few inches from the floor. My hamstrings quivered with the desire to sprint me out of the room, but instead of fleeing I chose to stay connected to the experience I was having. Within seconds of bringing my awareness to the sensations I was feeling, my abdominal muscles gave over to gravity for the first time in who knows how long. My diaphragm released toward my pelvic floor, drawing a huge breath into my body, and a wave of sound rushed past the lump in my throat as I exhaled and sobbed.

What kept me in that class, and each one that followed over twenty more months of grad school, was the care my teacher took with me during that first vulnerable roll-down, a need to go deeper in my acting work, and the fact that I’d moved across the country to go to grad school and wasn’t going to let fear trump my desire for transformation. But perhaps the biggest thing that spurred me forward was my curiosity about that first free breath my body involuntarily drew in and the uninhibited sound that followed.

Allowing breath to flow freely, liberated from mind or body contraction, is deeply challenging. But for the purposes of acting and public speaking it’s a necessity. When an actor’s breath isn’t in flow, neither is their voice, the text they’re speaking, their thoughts, intuitive impulses, or playfulness—all of which are present in great acting. More often than not, when an actor is holding their breath it is because they are experiencing an involuntary response to perceived danger, commonly referred to as fight-flight-freeze response. Sometimes that response is mild (e.g. when an actor auditions for an artistic director who has worked with them before and who loves them) or massive (when an actor is auditioning for the lead in a TV series and the semi-important LA director whom they have never met before is in the room). Either way, fight-flight-freeze response is something all actors experience at some point, to greater or lesser degrees. Voice practice is one way that an actor can begin to be in relationship with that response.

I say “be in relationship with” because in the twenty-plus years I’ve been teaching, acting, and directing I have not worked with one actor who doesn’t experience fight-flight-freeze response. I have devoted more and more of my work to helping actors come to terms with this occupational hazard, introducing them to a practice that helps them work with their particular performance anxieties rather than pretending they’re not there. As fight-flight-freeze response is an unconscious response of the sympathetic nervous system, it’s something an actor has to negotiate on an ongoing basis, because it never goes away. In my own case, I can honestly say that even after the many years I’ve been doing my own voice practice and teaching it to others, I’m just as neurotic as I was when I got on this path. The difference now is that I’m able to dance with anxious impulses and feed them into my work.

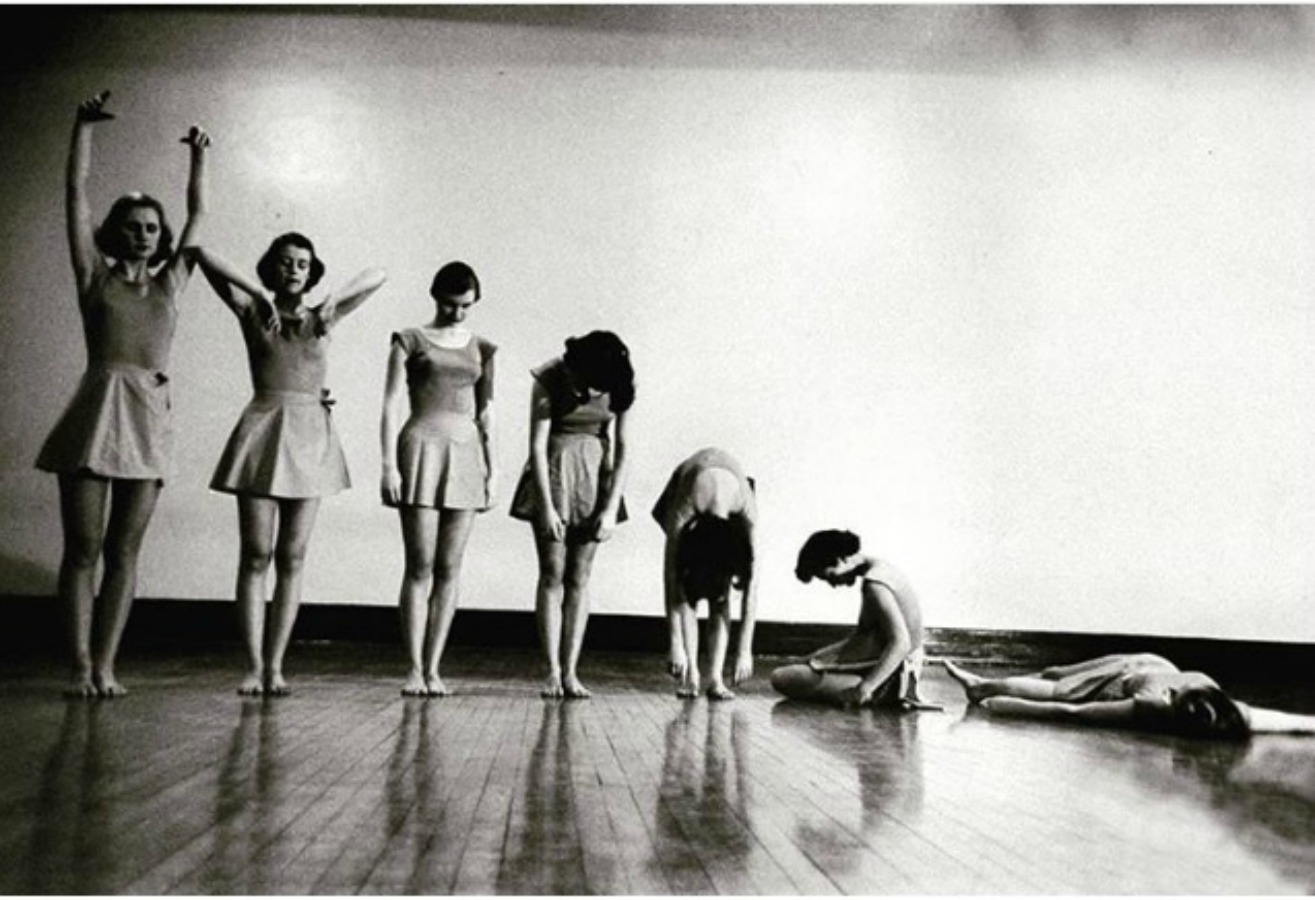

“Peephole into Voice Class,” photo by Fred Penner

Recently I read a book called Buddha’s Brain, which deepened my understanding of fight-flight-freeze response and affirmed that the increased awareness that arises from doing an ongoing, daily voice practice can help an actor manage it skillfully. Written by psychologist Rick Hanson and neurologist Rick Mendius M.D., the book refers to a phenomenon called “negativity bias,” which is, in a nutshell, the propensity for our brains to be on the alert for danger at all times. An evolutionary response from our caveman/cavewoman days, negativity bias grew out of a need to be able to assess and react to any possible threat that may be looming. Given this—that a degree of hyper-vigilance is at play in human beings at all times—performers have it twice as bad as their fear response kicks into overdrive on a regular basis.

Actors feel a tremendous sense of risk when putting themselves in front of people they feel are quietly judging them. Whether it’s in the presence of a casting director, acting teacher, agent, or director, actors are required to do two things that are high on the list of human stressors: job interviews and public speaking. Both of these stressors involve dealing with fears around potential criticism, being compared to others, losing jobs in the past, and even the fear of appearing anxious. But going to acting class, taking a meeting with an agent, auditioning… These are all critical elements of an actor’s life. Actors love acting, so why doesn’t the love of acting outweigh the anxieties that come with the job?

When an actor receives news that they have an audition, two reactions usually occur: “YAY!” and “FUCK!” “YAY!” because it may have been a while since an audition came down the pipe, and “FUCK!” because audition = job interview, and now the pressure is on. I’ve observed actors behave at an audition (or in a scene study class or an on-camera class or a movement class or a voice class) as if a mama bear with its cub is in the room. Sometimes the camera itself can ignite flight-fight-freeze response. (I don’t think it’s a coincidence that we call the lens of a camera a barrel, which is exactly what that long bit on a gun is called. But I digress…) Given the brain’s negativity bias, “FUCK!” frequently wins out over “YAY!” and actors don’t start breathing freely until an audition or a performance is over—once the perceived danger they felt they were in has passed.

Until an actor is able to observe their spinning mind, they will be at the mercy of their anxieties. If an actor thinks they’re not “right” for a part, that the casting director/teacher/actor/director they’re working with doesn’t like them, or that they’re a fraud (amongst many other possible thoughts that get triggered in a performer), then fight-flight-freeze response is sure to result. Thoughts like these are connected to the future (an outcome) and the past (previous experiences). If, however, these thoughts can be seen for what they are—empty—then no problem. They’ll come and go like clouds passing through a clear sky, and the body, breath, and voice will remain open, playful, and expressive.

One way an actor can instantly reconnect to the present moment is to bring awareness to breath and the physical sensations that accompany it. When an actor learns how to direct their mind to the rise and fall of, say, their belly, or the inflation and deflation of their back ribs, their awareness lands on whatever phase of the inhale/exhale cycle that’s occurring in that place at that moment. They don’t land in the breath that just passed or one that’s coming in the future—they’re with sensations that are of the present. If they can rest in awareness as they observe their breath arriving and leaving, mind and body begin to calm, breath begins to naturally deepen, and the actor returns to the here-and-now.

Learning this practice starts with bringing awareness to one single breath. From that first breath, possibility is born. Breath is the vehicle of sound after all, and words are merely sounds full of vowels and consonants, that, put in a certain order and articulated a certain way, become sentences and stories and poems and songs. Furthermore, the vibration of sound carries emotional content, need, and purpose. If an actor’s acting partner is their target in a scene, it follows then that an inhale dropping in is like the drawing of a bow and sentences containing action/need/intention are the arrows that fly across to the acting partner. When the arrows land, the acting partner will feel them and react accordingly, sending back arrows of their own. As playing starts to flow in this way, it’s sure that the breath/voice are flowing too, and the mind is directed where it needs to be. At this point there is a kind of fearlessness that enters an actor and an increased capacity to take risks—so much so that it can seem they’re improvising scripted, rehearsed material. Fears of “getting it right” go out the window and the actor experiences their true authentic self inside the material they’re playing with, not the terrified, tight, no-fun version.

Many years after that transformative breath/sound experience in my first grad school voice class (a couple decades into my work as an acting/voice teacher), I began training an accomplished ballet dancer. She was making the transition from dance to acting and came to me on the recommendation of a colleague of hers. After our first class together, I could see that contained within the long, restrained line of her body was a huge heart, powerful emotional force, and a big, free voice. On class two or three, after doing a check-in (scanning breath/mind/body/emotional state) and a physical/sounding exploration, I walked over to her and asked if I could place my hand on her belly. Hers was a body that was used to decades of teachers’ hands being placed on it and I could feel her belly tighten in anticipation of being “corrected.” I told her that the presence of my hand held no expectation, but was simply a surface against which she could feel her belly moving (or not moving, as the case may be) and invited her to bring her awareness and curiosity to the area below my hand, which was taut and held. She did. Then I invited her to see if she could soften the area and allow (rather than force) a breath to drop into it. After so many years of being rewarded as a ballet dancer for pulling her tummy in and up, my request ignited feelings in her of fear, shame, and anger. Vulnerable and threatened, she tightened her belly even more, holding her breath as tears came to her eyes. But soon her curiosity won out over her fear. Observing (rather than reacting to) the many complicated feelings rising in her being, she slowly, delicately allowed her abdominal muscles to release their grip and a big, round breath dropped into her belly just below her navel. Then the tears REALLY started—and with them flowed the sounds of grief, relief, and joy.

With that first uninhibited inhale/exhale cycle, this actor/dancer began to negotiate and work with fight-flight-freeze response. It was a powerful moment for her, and set her on a path of daily practice that she is still on. Experiencing that first breath was not easy for her—and the truth is it’s not easy for any actor, regardless of their background. For trapped in the muscular contraction of breath are unspoken thoughts and feelings, physical pain, and suffering, and the many personal stories that make up an actor’s life; stories that resonate with the lives of the characters they play. Being with the enormity of one’s inner life can be overwhelming the first time, but, as with all things, the feelings don’t last forever. Over time, with each breath, sensations and emotional responses become more familiar and can be put directly onto voice, words, and text with a sense of ease and purpose.

Starting an intimate relationship with one’s breath and fight-flight-fear response is a major commitment and not for the faint of heart. It requires a tremendous amount of courage to observe the breath/body/mind as it is. Not everyone is up for the journey and the truth is there are a lot of really fine actors who’ve never stepped foot into a voice class who do just fine negotiating performance anxiety and have successful careers. Turning to the breath when one is lost is just one way. The reason I am devoted to and encourage this particular practice is because until an actor has shuffled off this mortal coil, the breath is always there. An actor doesn’t need any equipment to direct their awareness to breath, and the practice can be done anywhere: in a subway, standing at the kitchen sink, waiting in line at the bank, playing with a child, ordering a coffee, sitting in an audition waiting room… The possibilities for practice are endless, and once embraced, the practice itself becomes the teacher.

Comments