Sir John, Shawn, Richard, and Me

I had applied myself enthusiastically to the audition process, booked the gig, taken a deep breath of satisfaction… and proceeded to lose sleep. Odd, really, because in most cases getting a good part in a strong play with accomplished collaborators was all I needed to feel secure in the integrity of my job as an actor.

But I was to play Canada’s first prime minster, Sir John A. Macdonald, arguably the most popular and most polarizing politician in Canadian history. The idea of shouldering the mantle of Macdonald’s legacy on stage was giving me the jitters.

As professional freelancers, we actors are most often hired as interpretive artists, and while the aesthetic and political aspects of a production may be important markers for our belief in that work, these factors are not usually at the forefront of our creativity or responsibility. Within the given system, we are not exactly mercenary as cultural workers, but we are certainly open to seizing opportunity.

That said, I started to wonder about my personal responsibility—as an actor and citizen—in portraying the preeminent “Father of Confederation” today, and to do so not only during this year of our controversial Canada 150 “celebration,” but also in the National Arts Centre’s new $110.5 million renovated Ottawa building. Most saliently, I struggled with what it meant to tackle this role in the face of the continuing and still barely addressed legacy of Macdonald’s active contribution to cultural genocide (which, effectively, was population decimation): the military suppression of the Red River uprising, the hanging of Louis Riel and eight other Aboriginal leaders, the starvation of the Plains Cree, the establishment of Indian reserves, and the laying of groundwork for the Residential School system.

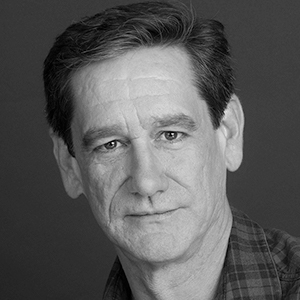

Martin Julien in the NAC’s production of Sir John A.: Acts of a Gentrified Ojibway Rebellion. Photo by director Jim Millan

The play in question is Sir John A.: Acts of a Gentrified Ojibway Rebellion, written by Drew Hayden Taylor. Certainly, Taylor had written the part of Sir John A. from a substantive, informed, and legitimate position as both accomplished playwright and Indigenous writer. But the integrity of his work isn’t something I can simply hide behind as a white actor. I must find a way to actively embody that integrity through my exploration and presentation of the dramatic character.

If I believe in the writing and the characterization, then my first responsibility is to apply my skill and technique towards the (re)presentational fulfillment of the playwright’s work. But, really: might there be a greater responsibility to myself, my collaborators, my audience, and my country when I display my voice and body as if they were Macdonald’s?

I’m not the first actor to play Sir John A. in recent years, and I knew two people who could help me with my questions. Since I was losing sleep, caffeine was in order. Richard Clarkin and Shawn Doyle agreed to meet me at Jimmy’s Coffee on Ossington in Toronto.

the idea of shouldering the mantle of Macdonald’s legacy on stage was giving me the jitters

The place is full of books. Reference works, old encyclopaedias, how-to manuals. And, strangely, a copy of Old World, New World: The Story of Britain and America by historian Kathleen Burk, which was right by my elbow where I sat down, as well as a giant eight-by-twelve foot map of the Dominion of Canada in 1882, installed on the wall behind me. Either these were signs of an auspicious beginning to our planned conversation about colonialism and representation, or they were merely relics of a traditionalist history, mounted and shelved as props for the more freewheeling displays of smartphone and Americano intersectionality that surrounded me.

Richard arrived shortly after me. The night before, he had played an outrageously gleeful and besotted Macdonald in Michael Hollingsworth’s Confederation Part 1: Confederation & Riel for VideoCabaret at Soulpepper; tonight he would essay the man again in Confederation Part 2: Scandal & Rebellion. For all that, he seemed refreshed and in a generous mood. Good! I was feeling somewhat sheepish about my insistence on holding this palaver with two busy friends. I was an actor hired to play a part—what was I so anxious about?

Richard Clarkin as John A. Macdonald (centre) in VideoCabaret’s Confederation Part II: Scandal & Rebellion at Soulpepper (2017). Photo by Michael Cooper

Shawn appeared right on Richard’s heels. It had been seven years since Shawn’s intensely rooted Macdonald performance was first broadcast on CBC television in the movie John A.: Birth of a Country. I bet the last thing he wanted to do was talk about Macdonald in 2017. Turns out I was right.

“Oh, I just got so sick of it,” Shawn said, as he settled in. “The idea of me saying anything about John A. is not at all interesting.”

“Did you overdose on it, playing the part?” I asked.

“It’s all in the Indigenous perspective for me now. [But back then] I had taken on a role. I had done research, which was clearly limited. I absconded my responsibility in a way. I just feel that I let it down,” said Shawn, before adding: “I’ve really gotten educated since.”

“There’s still not a lot out there for research,” Richard added. “I relied heavily on the Richard Gwyn biographies.”

Shawn and I both knew Gwyn’s mammoth 1200-page two-volume biography of Macdonald: The Man Who Made Us (2007) and Nation Maker (2011). In fact, the CBC film was based on Gwyn’s first volume. The second volume, unfinished at the time of Shawn’s primary research on the role, goes into great detail regarding Macdonald’s dire actions towards Indigenous people, but only recently has the importance of this woeful history been given a greater hearing.

“You can find a lot more dissenting opinion now, I think, with Canada 150 happening,” Richard pointed out. “But it’s still not mainstream.”

“First Nations issues were not the focus of the movie when we shot it,” says Shawn. “It was not the nature of that role, at that time, to go into any of that stuff. The perspective was pretty much on John A. as the hero—very sweeping and general and romantic.”

Shawn gave a tired grin and let out a sigh. I could see that he had grappled with the same question that I was wrestling with, with regard to the actor’s responsibility to a project; to its politics, style, and view on history.

“Michael Hollingsworth takes no prisoners with John A,” Richard piped in. “He doesn’t come out looking good in our production. And I don’t, in my interpretation of him, shy away from his darkness, his alcoholism, his passion for the country, but also, at the time, his wrongheaded idea of assimilating the Natives into the ‘civilized’ population, so to speak. And he was the architect of the horror that were the Residential Schools. Clearly. The research backs that up.”

I babbled on about my relationship to the research on the historical figure, taking pains to point out that playwright Taylor had drawn a very charismatic and humane portrait of the man that, although ultimately damning, did not lack for nuance in characterization.

“But don’t be afraid to play the villain that’s there, Martin!” Richard offered enthusiastically. “I’ve played a lot of dark parts—I know Shawn has too—and there is great joy for the actor in relishing the opportunity to occupy the shadows of the human psyche.”

“True, but…” I countered, “maybe it makes a difference when it’s is a real figure from history whose actions still have such an effect on the present day, whose legacy is still in active contention.”

Shawn Doyle in CBCs John A: Birth of a Country. Screen grab from film.

I had slipped my way into defending a position that Sir John A. was—if not exactly enlightened regarding what he called “the Indian problem”—then at least more knowledgeable about and interested in the First Nations than most of his contemporaries. “He had thought and cared about the ‘problem’ all along,” I said. “All of his policies and conclusions are deeply problematic now, but it’s not exactly something he didn’t think about…”

Shawn decided to jump in again. “I don’t know if you know, but I’m actually First Nations. I discovered it after I played John A. I got my First Nations status as Mi’kmaq. So that has obviously led to another light on this.”

I dug myself deeper. “He took an active interest in the Indian question, and knew Indians, and… defended them in court as a young lawyer, and… sang in a Mohawk choir, and…” Blah, blah, blah. “But it’s complex, right?”

Shawn heard me out. Then, softly and evenly, said, “But you don’t think—and I don’t know this, I’ve not read enough on it—but, you don’t think his interest in all that was as a result of it being a challenge to his… ‘vision’?”

Now it was my turn to listen. He went on: “For me, if you get into an active dialogue about Macdonald with an Indigenous person, that is an argument that would start major contention, and anger. The idea that John A. was positively interested in Indigenous or Native affairs would set anybody off… It’s not a history any of us can support anymore.”

This moment of exchange was the real crux of our long discussion. Because, in this supportive setting, I had actually acted out what my inchoate fears were with regard to this role. And, of course, it had everything to do with being an actor. A big part of my job was to take this marvellous and deeply flawed character that Taylor had written and advocate for him through rehearsal and on stage. Only with a certain level of personal identification and valorization could I bring the character to life.

Here I was, though, advocating for John A.’s position amongst friends in a coffee shop, and doing so with little consciousness of my intrinsic—if temporary—immersion in his self-congratulatory racist worldview. It wasn’t enough that I knew, abstractly, that Macdonald’s policies and actions were often abhorrent and indefensible—that knowledge needed to be leavened by the fact that, as an actor, I would find myself embracing the man’s own self-regard.

Here is why I was losing sleep. I would have to balance my awareness of the performative ambiguity that results when an actor plays a historically influential character, who is in some ways severely flawed and culpable. The balancing act was between my professional regard for the humanity painted by Taylor in his characterization of John A. and my knowledge of the very real transgressions and hollow justifications—equally outlined by Taylor—of the man himself.

there is great joy for the actor in relishing the opportunity to occupy the shadows of the human psyche

Perhaps it was clearer from the beginning for Richard in the notoriously theatrical version of the prime minister that VideoCab evokes in The History of the Village of the Small Huts cycle. It is, possibly, Richard’s confidence in this material—the playwright’s research, the company’s style, his experience with the genre—that gave his performance of John A. such élan and giddy buoyancy. And I realize that I might greater celebrate the confidence I have in Taylor’s work, my collaborators’ contributions, and the strength of the entire project.

It was only a few days later, after digesting the weaving arguments of our conversation, that my own potential for commitment was succinctly reflected back at me in a short email exchange with Shawn.

“I just think the fact that the play is being done, at this time, says so much,” Shawn assured me. “From the start, you told me you loved Drew’s play. You clearly had a very positive response that you can trust from reading the play that first time. Trust that.”

It has often been observed that we are not a country that much recognizes or indulges in its own history. I was grateful to track down Richard and Shawn, who have some intimate knowledge of what it’s like to embrace, through performance, such a dynamic yet troubling figure as John A., whose past actions continue to have real consequences.

Before we parted, my supportive duo of duelling Macdonalds encouraged me to reach out to my colleagues at the National Arts Centre and initiate a dialogue about who our audience is for this show, and what we want to share with them. Empowering advice, and one that we, as a creative team, have begun to address. The recent resolution by the Elementary Teachers’ Federation of Ontario to remove Macdonald’s name from public schools, while not universally applauded, is another clear sign that our collective conversation has also just begun.

Comments