The Night Sizwe Banzi Was Born

South Africa, 1972.

The government has driven all organizations who believe in a multi-racial, democratic South Africa underground. Political groups representing every non- or multi-racial alliance are banned. The Natal and Indian Congresses (two leading Black organizations), the Pan-African Congress, and the African National Congress have all been banned by the nationalist government. Their leaders, Robert Sobukwe and Nelson Mandela, are serving the 12th year of their life sentences. The apartheid government seems to have prevailed. It’s a police state. A strange silence has fallen over the nation.

In Grahamstown, a conservative English-speaking town in a shallow valley in the Eastern Cape, police vans prowl the Black township. The Security Police have set up roadblocks as they search for the leader of a new political movement — Steve Biko, founder of the Black Consciousness Movement (BCM) — and his followers in the Black People’s Convention.

Down in the Great Hall of Rhodes University, a group of anti-apartheid students are prepping the space for an unnamed mystery play, the opening event in their annual arts and science week.

Athol Fugard, South Africa’s most revered playwright, has been operating as a writer, actor, and director under the constant threat of banning and censorship. He’s working with a collective of Black collaborators, the Serpent Players, who have been banned from performing in their home city, Port Elizabeth, an hour and a half away. Rumour is the mystery play is their latest work, and they’ll be performing it for the first time at the university. But my organizing group, Aquarius, the cultural wing of the National Union of South African Students, has been told not to say a word.

No publicity. No tickets. The law prohibits Blacks and whites from performing where money is exchanged.

About a hundred students and lecturers walk into the Great Hall to find chairs and cushions arranged beneath and in front of the stage, on the bare wooden floor. The Hall is plunged into darkness.

Don McLennan, an English lecturer and a longtime friend of Athol Fugard, walks to the front of the audience.

“Welcome,” he says. “Tonight we are gathered for a special play. First, would the Security Officials Branch please identify themselves?”

A man in a raincoat towards the back shuffles, standing uncomfortably. Every political gathering is under observation, so we are used to those like him.

“The doors please.”

Three student guards lock the back doors and stand sentry outside. A raid is quite possible. It’s happened before to the Serpent Players, and other cultural groups. The siren, the flashing lights, the hushed conversations, the arrest forms, the argument, the shutdown.

“Without further ado: Athol Fugard, John Kani, and Winston Ntshona present Sizwe Banzi is Dead.”

Two figures shuffle in. The lights come up.

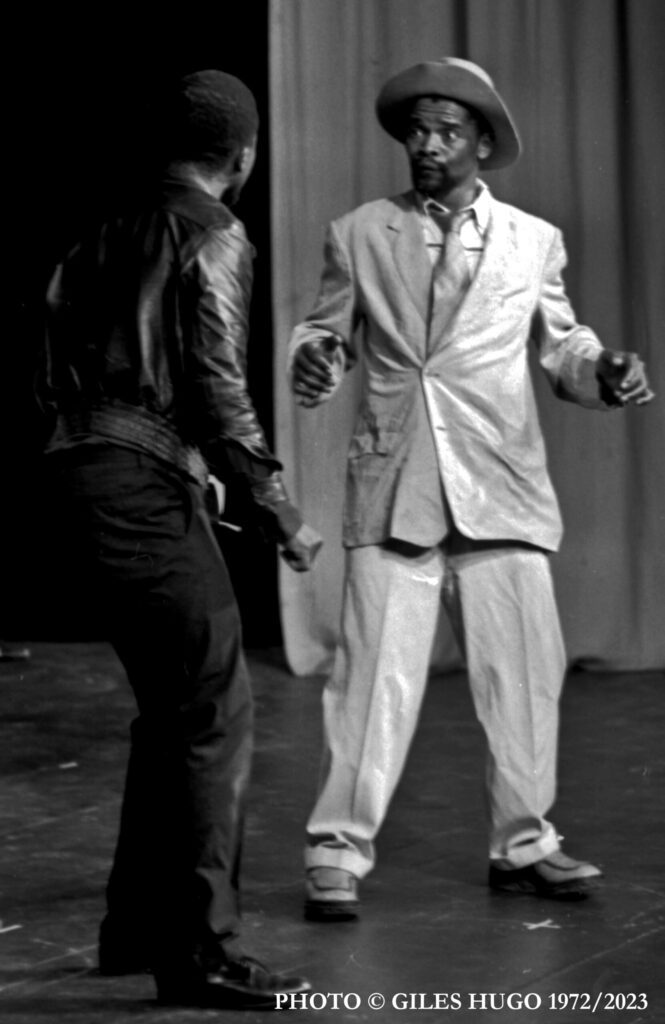

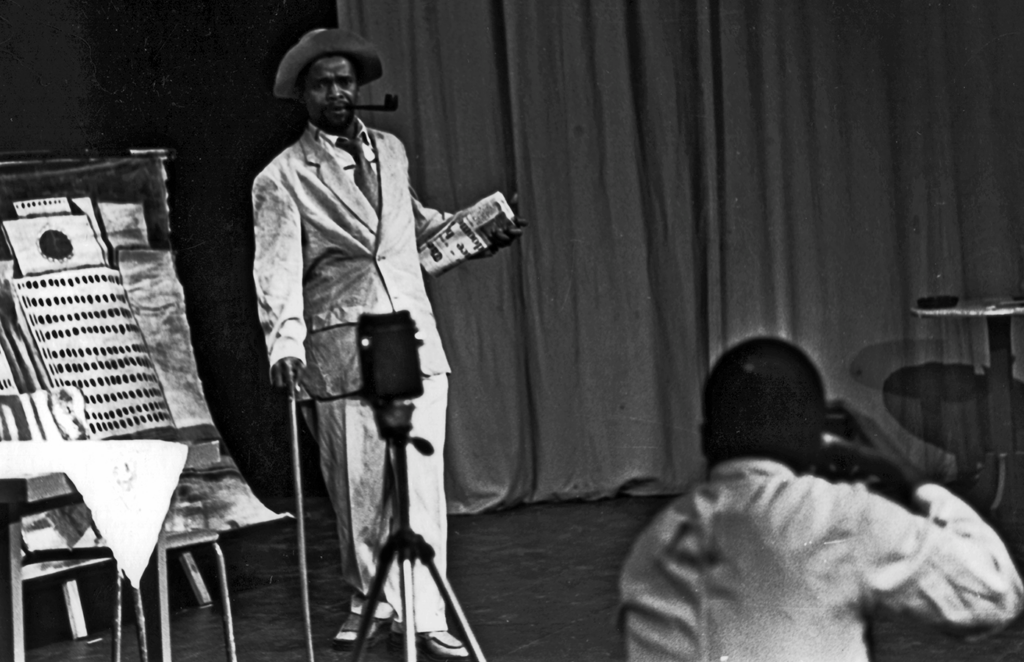

We are in Styles’ photo studio, the opening scene of Sizwe. The owner, a kinetic John Kani, welcomes a customer, the tentative Sizwe Banzi, played by Winston Ntshona.

Thence follows one hour of the most electrifying theatre any of us has ever seen.

The content, the story of men whose lives were circumscribed by the “dompas” — the pass book, the millstone around the necks of 17 million Blacks in a land where 3 million whites, myself among them, moved freely — was an education and a radicalization.

The fact that many of us were unfamiliar with the torturous oppression of this document says much about why dictatorships last longer than they should: why comfort for an elite prolongs the oppression years after it has exhausted itself.

Now at the age of 72, I can look back and say it was the most politically incendiary piece of art I have ever seen.

It must have felt similar in Czechoslovakia when Vaclav Havel produced The Memorandum. In Chile, Dorfman plays under Pinochet. In China, in Russia, Iran: anywhere and everywhere, oppression, repression, racism, injustice, autocracy, and dictatorship rules, yet there is something intravenous about underground political theatre. Until the early seventies, it beat the newspapers, radio (no television in paranoid South Africa), movies, rallies, speeches, and books to the punch, hitting hard at the suffocating details of daily injustice, especially for the disenfranchised Black majority at that time.

Because we were articulate, well-read university students, we did know of the pass system, if only vaguely. But we had little idea of what it was like to live within it every day, every year.

All of our families were complicit because we couldn’t hire Black domestic servants or farm labourers unless their pass book was “in order.” How many times had I seen hopeful jobseekers line up at our back fence, all showing their passes, tapping them as if to say, “I am human; I have Prime Minister Vorster’s permission to live in this part of South Africa, I can take this job you may or may not have. Please, please give me this job,” while waving the dompas, the wrinkled treasured booklet. “Only with this can I feed my children.”

If anything illustrated the imprisonment of apartheid, to me, it was this torn and frayed booklet.

Kani, who was the Olivier, the Brando, of the oppressed, was explosive that night, a bomb ticking before our eyes. In the play, he ignited a frustrated admission from the more docile Ntshona:

“What’s wrong with me?

I’ve got eyes to see. I’ve got ears. I’ve got a head to think good things. Am I not a human being? Look at me, my friend. … Take this book. Take this book and tell me what it says about me, boet. Does this book say I am a man, boet?

Does this domboek say I am a human being, boet?

This domboek my friend. Wherever you go it says domboek.

You go to church to sing good hymns. You’ve got to carry a domboek.

You go to town to buy food for your family. You must have a domboek.

In your own house with your children this domboek must be in your pocket.

Even when you die in hospital this domboek must be there.”

The hardware of oppression, by the book.

Forty years is a long time. I can’t help but wonder: how accurate is my memory of that night?

Facebook can occasionally be a wonderful thing. I put a message on an alumni group page called Old Rhodians Knocking on Heaven’s Door, asking if anyone remembered the performance that night in Grahamstown, the first ever performance of Sizwe Banzi is Dead.

Dozens replied from South Africa, America, and Europe, now scattered far and wide.

“Brilliant play”

“Extraordinary theatrical experience”

“A very clandestine event”

The exact details of the pass system in ’70s apartheid South Africa may not be relevant to the lives of urban Canadians today. But the message Sizwe Banzi carries, the voltage of that message, is as relevant as ever: Sizwe Banzi was like a report from the frontlines of apartheid. It was also a universal story of how people behave, and bond, and scheme, under an oppression so all-smothering.

What is the power of theatre to ignite political action?

That small group of us in South Africa left the Great Hall that night doubly resolved to do what we could to reverse 300 years of the most tenacious racial discrimination in history. Sizwe Banzi, along with the BCM, the African National Congress, international revulsion, Steven van Zandt and his protest group Artists United Against Apartheid, arms and economic boycotts, would all bring apartheid down.

It would still take 20 more years before Nelson Mandela walked free.

But for us, it was the best that theatre can do.

One cannot help thinking of LGBTQIA+ people in Africa, women in Iran — victims of discrimination everywhere — while watching this play. And how a Sizwe Banzi for each of them would help transcend boundaries and raise global awareness.

And what it forged in me: a determination to wear this thing down until it collapsed under the weight of its own contradictions and inhumanity.

Sizwe Banzi Is Dead runs at Soulpepper Theatre May 25 to June 18. Tickets are available here.

Special thanks to South African playwright and theatre historian Anthony Akerman, whose research and support was very helpful with the original production and this article.

Comments