The spectacle of suffering: Toronto theatre’s addiction to trauma porn

Trauma is everywhere in Toronto — on the streets, subway, and stage — and maybe that’s why I’m so bored by it.

Turn off your morning alarm, and your phone will immediately feed you a list of atrocities that occurred overnight. Step outside, and you’re immersed in the bleak, unforgiving hellscape of an under-resourced metropolis. It’s only natural, if not easier, to walk head down, feet forward through the suffering that surrounds you.

But aesthetic distance dissolves that friction, and now, maybe it’s OK to look. Maybe it’s worse if we don’t.

So forgive me if I’m uninterested in being tear-jerked off by yet another one-act play that sheds a light on the violence, oppression, or complicated family dynamics of [insert marginalized group here]. I don’t need my disadvantages brought to light.

I want them dealt with.

Good intentions have been pent up since lockdown. Depictions of brutality were captured, fabricated, and circulated faster than they could be understood. Black Lives Matter became a global movement, provoking artistic leaders and organizations to unpack their feelings of helplessness and show solidarity through action.

If we’re so drawn to the spectacle of suffering, why has it begun to feel so mundane?

Now that HR policies have been updated and reading lists have been curated, it’s time for theatres to speak truth to power.

But the truth isn’t always what grabs people. It’s emotion. It’s the catharsis of losing yourself in the misery of others while nothing in your own life has to change. It’s the repressed pleasure of patting yourself on the back for listening to someone explain their daily disadvantages, or maybe giving them the microphone.

Somewhere along the line, we conflated allyship with engagement. And in the rush for representation, trauma became the primary frame of reference for people to understand and sympathize with the ~marginalized~ experience.

Not joy. Not comedy. Not intellect. Always pain.

Also known as “trauma porn”, what distinguishes this phenomenon from a story about trauma is when trauma is approached as an event rather than an experience. Trauma porn is not a category of sexual pleasure, but instead, refers to an alternate definition of pornography that means: “to arouse quick intense emotional response through sensationalized portrayal or activity.”

The depiction of trauma is meant to speak for itself, especially if the story has nothing else to say about it. Violence is simply actualized rather than addressed.

How often does police brutality need to be reenacted for people to understand it shouldn’t happen, but does? How many plays about residential schools need to be produced in order for Indigenous artists to be recognized for their craft? Is there no room for queerness in programming unrelated to coming out, coming of age, or the AIDS crisis?

That is the underbelly of trauma porn’s gratuitous nature. With increasing exposure, injustice is now understood as inevitable, reinforcing complicity in the face of cruelty. Worst of all, we become unmoved when seeing certain bodies experience pain — because we expect them to.

In turn, this voyeuristic approach to doing the work — the commitment and undertaking of social progress — keeps artistic organizations and audience members from engaging any further than they’re used to. Oppression gets to be programmed instead of dismantled. Rarely is the audience meaningfully implicated in the narrative, their spectatorship distinguishing themselves from the presented villainy.

Trauma porn doesn’t start and end with racism, but racism-themed plays are a recurring programming trend across the city. Yet for the most part, theatre in Toronto doesn’t handle white supremacy any differently from how we experience it in the everyday world. Plays about racism serve less as a disruption and more as a balanced diet of morally-aligned entertainment.

It’s clear who those stories are being told for. But let’s not underestimate older, white audience members so quickly! Many of them like to be challenged. Many of them are hungry for something refreshing. Others will shake their fists — but their loss of patronage may be a risk worth taking.

If companies are still looking to diversify their audiences, it’s not enough simply to produce works by or about the demographics we want to include. We have to tell the stories those people will want to hear. We have to learn how to connect with racialized artists and audiences outside of their encounters with whiteness.

So if companies are still looking to diversify their audiences, it’s not enough simply to produce works by or about the demographics we want to include. We have to tell the stories those people will want to hear. We have to learn how to connect with racialized artists and audiences outside of their encounters with whiteness.

Besides, I’m sure white people are tired of being told they’re complicit in racism, just as much as I’m tired of telling them.

By now, trauma porn onstage feels less like a cheap thrill and more like sex for the sake of procreation. But if we’re so drawn to the spectacle of suffering, why has it begun to feel so mundane?

To an extent, we’re desensitized to disaster. The sheer amount of information we encounter daily weakens our capacity to meaningfully absorb any of it, motivating reactivity without reflection. Images of cruelty no longer serve as evidence, but content. A picture of a body is no longer a body or a person; it is now a site of ideology.

But that delineation isn’t quite as distinct in person. If trauma is inescapable, what is the value or purpose of its literal reenactment? Is gritty realism worth the risk of retraumatization? Sure, intimacy and fight coordination is a vital safeguard for the performers involved, but that care has yet to be sufficiently extended to the audience.

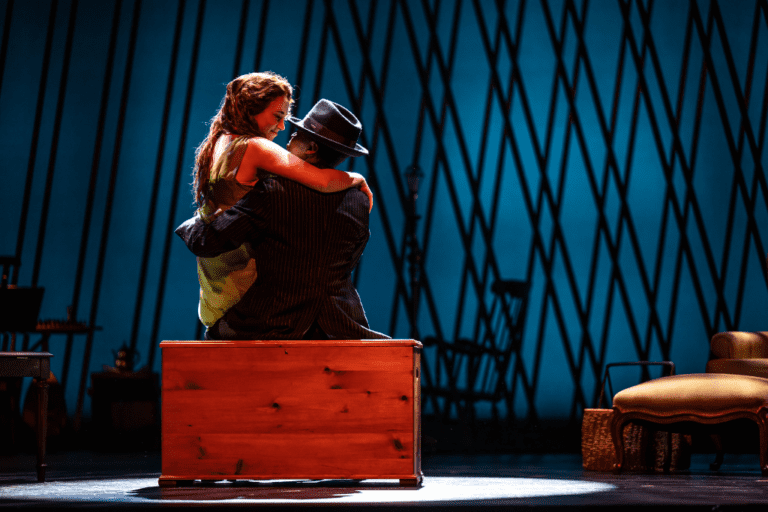

For instance, the 2023 co-production of Fall On Your Knees received specific criticism for its highly literal adaptation of the 1996 Canadian classic novel. Toronto Star critic Karen Fricker noted, “part of what makes the book so compelling is how much imagination, music, and love are woven into this story of transgression and taboo.” But the show’s inclination towards literary fidelity over theatricality struggled to situate the abuse and cruelty within the staged retelling.

More than ever, realism is conflated with quality. Appearance equals authenticity. Perhaps this is what fuels our cerebral, rather than experiential, approach to staging traumatic subject matter.

Yet the inherent nature of theatricality should make us question that decision! It’s the tangibly overt artifice of theatre that we often find ourselves comforted and unsettled by. We don’t always need to see violence to recognize how it feels.

Crow’s Theatre’s recent production of Dana H. is a textbook example of that at play. Compiled from interviews with the real Dana Higginbotham (writer Lucas Hnath’s mother), the audio track recounting the story of her kidnapping is entirely lip-synched by an actor (in this case, Jordan Baker) seated in a replica of the motel room in which she was held captive.

In Dana H., Baker becomes an uncanny puppet for Higginbotham, whose matter-of-fact delivery of every gruelling detail is a heartbreaking contrast to the extraordinary technical feat of Baker’s performance. It’s then exceptionally gut-wrenching to hear Higginbotham describe the day after she is brutally assaulted by her captor and not be able to attribute her voice to a body onstage.

In Crow’s mounting of Dana H., that moment was visually scored by a stagehand dressed as a cleaner, nonchalantly turning over the room as if the furniture was never broken and the sheets were never soaked in blood. As if the worst period of Higginbotham’s life never happened or mattered.

Yet this is not a play meant to garner sympathy or tears. Baker’s embodiment of Higginbotham compels the audience to focus on who the speaker is, rather than what happened to her. And it’s the impulse for abstraction baked in Hnath’s piece that inventively confronts whether or not we “only exhibit empathy when it feels emotionally convenient.”

I’m not suggesting that trauma should be forbidden onstage. But responsible practices for staging violence (for example, fight coordination, intimacy direction) cannot only be internal.

It’s high time we also get creative with what audience support can look like. Existing measures such as content warnings, resource databases, and active listeners may be available, but those resources often lack a personal connection from the artistic team or producing company. Without that essence of humanity, audience care can feel like a front-of-house checklist rather than a symptom of meaningful engagement.

We need to understand how to dress the wound and not just how to poke it. Artistic leaders should seriously reconsider both programming and staging trauma if they are not yet equipped to purposefully address the ramifications of staging trauma badly. I dream of a future where audience care can be treated as an access need rather than coddling.

Theatres in Toronto may currently have an addiction to trauma porn, but marginalized people deserve to be asked what brings them pleasure — not just their pain.

And hey, the first step to fixing a problem is admitting you have one in the first place.

Comments