Truth, Reconciliation, and Zahgidiwin/Love

As an emerging playwright of Indigenous descent, there’s a pressure for me to be a spokesperson for and a gatekeeper of an ancient civilization I am only beginning to understand. It’s important to clarify that I do not speak on behalf of anybody or any group of bodies.

Growing up in a half-Anishinaabe, half-Slovene family in Winnipeg, Manitoba—“the most racist city in Canada”—was a lot of fun, if you’re the kind of person who finds prejudice a blast. Moving to New York City for graduate school, I had my first taste of blissful ethnic invisibility, and I loved it. I spent countless late nights wandering the city alone, never fearing for my safety in any racially motivated way.

In Winnipeg, for some of us, walking alone at night is a lot like walking through a theme park funhouse: You just never know what door that knife-yielding clown is going to pop out from. And because it’s rare that a day passes without hearing of another missing and murdered Indigenous woman, that sense of fear never quite dissipates.

I’ve been working on strengthening my understanding of Indigenous history and tradition for a long time in order to more successfully tackle these issues through writing in respectful and responsible ways.

I began to learn Anishinaabemowin. I incorporate six of the Seven Scared Teachings into my daily life (humility got cut, I blame Instagram). I watch North of 60. I am distracted by the overwhelming handsomeness of 90s Tom Jackson. I make bannock. I smudge, and smudge, and smudge some more.

Still, I have my doubts. How do I respectfully write about genocide and explore intergenerational trauma? Especially when I’m so flippin’ mad about it? Angry emoji! Poop emoji!

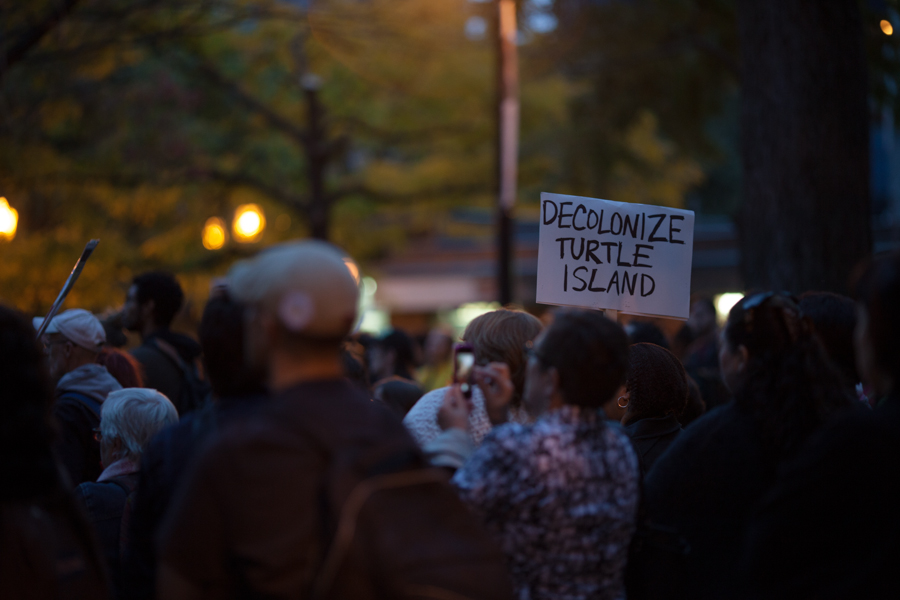

During a fit of rage on Christmas day, I lay on the floor of my grandmother’s house and wrote Zahgidiwin/Love, a decolonial comedy about loss—of language, of love, of culture, of land, of knowledge—in the era of truth and reconciliation. Through interwoven storylines across time and space, the play follows a young Indigenous woman as she fights for her freedom in a world of colonialism and patriarchal rule.

Despite the serious subject matter, I wanted this play to be a comedy. One of my greatest (or only, depending on who you talk to) strengths as a writer is my sharp wit indicative of a generation that grew up yelling at people on the internet. I believe it is a vital tool in storytelling and art as we begin to decolonize and rebuild as individuals and a nation.

The truth always makes for a better story than fiction, and I think there’s a lot of difficult truths on this path to reconciliation. How do we ask people to take responsibility for the actions of their ancestors without placing blame? With intergenerational trauma as part of the foundation of our daily lives, how do we ask for intergenerational accountability without making our friends feel so guilty they stop inviting us out for sushi? What exactly did we lose, and how exactly do we get it back? And when we get it back, how do we reconcile everything we knew, everything we lost, everything we’ve been taught, and everything we will learn going forward?

I don’t have the answers, but I think asking the questions in the right way is important. For me, that right way is often comedic… because I still want to get invited out for sushi.

Comments