Urjo Kareda was metal as hell

A million years ago, I was hiding out on an organic farm at Esalen in Big Sur, California, smoking too much pot.

This was before the internet, possibly before the sun itself was born. One day there was a pink slip on a message board from Urjo that read simply and urgently, “come home.”

When I was six my mother had ostensibly kidnapped me from Toronto, or what rich people call, “going to Esalen,” or “leaving for five years to Northern California to work on oneself.” My playwright father was broke, brokenhearted, and enraged at her for doing this to him. In response — like a pair of keys my mother had forgotten to return — she flung me across the border, illegally.

Please let me acknowledge my immense privilege in this scenario. Was I crossing the border at six, seven, eight years old with drugs in my underpants illegally? Yes, I was. But was I also as white as a Pottery Barn couch (Taupe? Eggshell? What the fuck is going on at Pottery Barn?)? Yes, I was.

While visiting my father back in Toronto, I told him I wanted to be a performer like Betty Boop — he forbade it. He said that we’d drive all over Toronto distributing headshots. Eventually I understood that I must be a playwright — that acting was a mental illness. Never mind he himself was a playwright who was always “ducking out” for weeks at a time to institutionalize himself, or what I learned to call, “daddy’s writing retreats in the nutter on the government’s dime.” What’s the point of universal health care if you can’t get a bed in the psych ward to clear your mind?

For five years I crossed the border illegally every six months in a long, drawn-out custody battle, until when I was eight, my father died of what people at Esalen call “unexpressed rage,” and what people in Canada call “cancer.”

And then we were home — Toronto. The trailers, drug dealers, crystals, and bong water loosely sloshed around in Big Sur were a thing of the past. I was rolling through The Six with my woes. I had slept on the streets of Toronto some nights during high school, because my mother would drive me away with her sometimes terrifying behaviour, writing angsty letters to Leonard Cohen from the Coffee Time at Bloor and Ossington.

You’re probably wondering, “where’s Urjo?.” Backstory matters. So does refraining from whining. I’m doing my best.

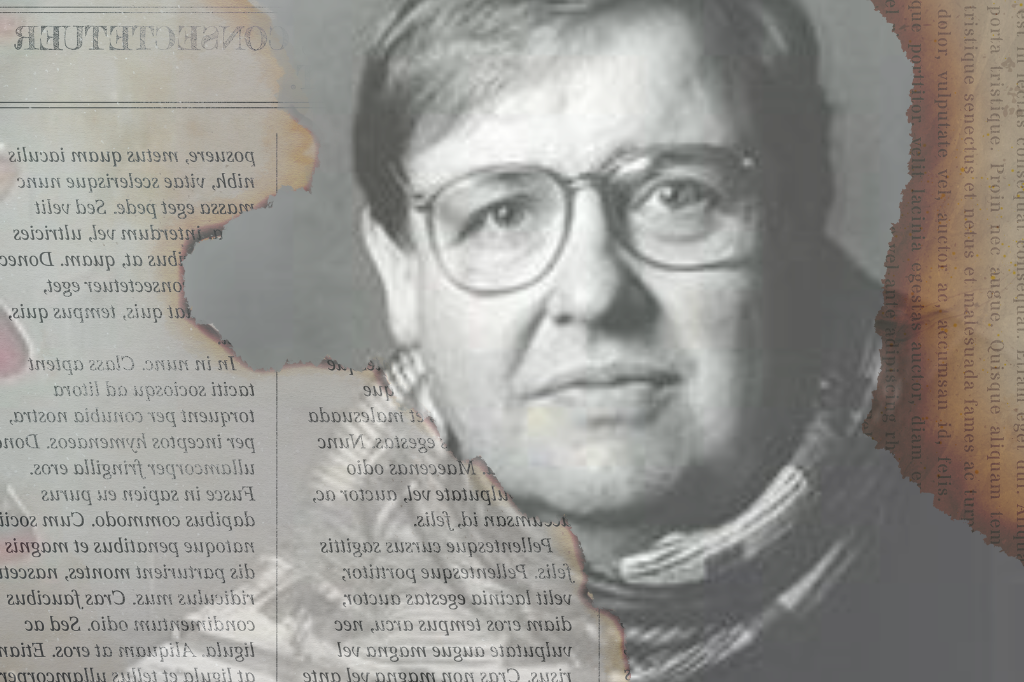

Even in dreams Urjo’s presence is intimidating.

Upon (barely) graduating high school, I was beginning to feel slightly untethered as I folded turtlenecks at Jacob in the Eaton Centre. While Christmas muzak destroyed my mind, I started to write a play about a second-generation Canadian playwright who folded turtlenecks at Jacob in the Eaton Center while Christmas muzak destroyed her mind. When this play won a writing competition I’d applied for the prize was a staged reading. At the reading I met Urjo.

He approached me and right away shook my hand. “I was a fan of your father’s work. You should follow in his footsteps,” he said. I wanted to scream “No, I’m a street kid. I’m a Bug Sur loser, a failed Betty Boop.” When he shook my hand, I felt my father’s hand through his hand, and a kind of spiritual transmission that said, “it’s okay to stay with us in Toronto.”

I immediately went back to Big Sur. A year later Urjo found me hiding out on an organic farm in Esalen and left a pink slip on a bulletin board that read “come home.” I was 19 when I was invited to join the playwrights unit at the Tarragon in Toronto.

When I arrived on day one at the unit — a table full of female playwrights, with Urjo and Andy McKim at the helm — I quit pot cold turkey. On day three of my recovery, I told them all how my father had visited me in a dream that seemed more like a metaphysical hang than any dream I’d ever had. I finally got to hug my father one last time. He made me promise not to pursue acting and instead reach for the highest height I could as a writer.

Urjo guided me through the unit with a steady hand. But I still couldn’t help complaining to him about how hard the work was. How could I possibly do it and not end up in the nutter like my dad? Every playwright is chasing the same toonies and loonies. You have to pray for philanthropy! He laughed and said, “it’s impossible.”

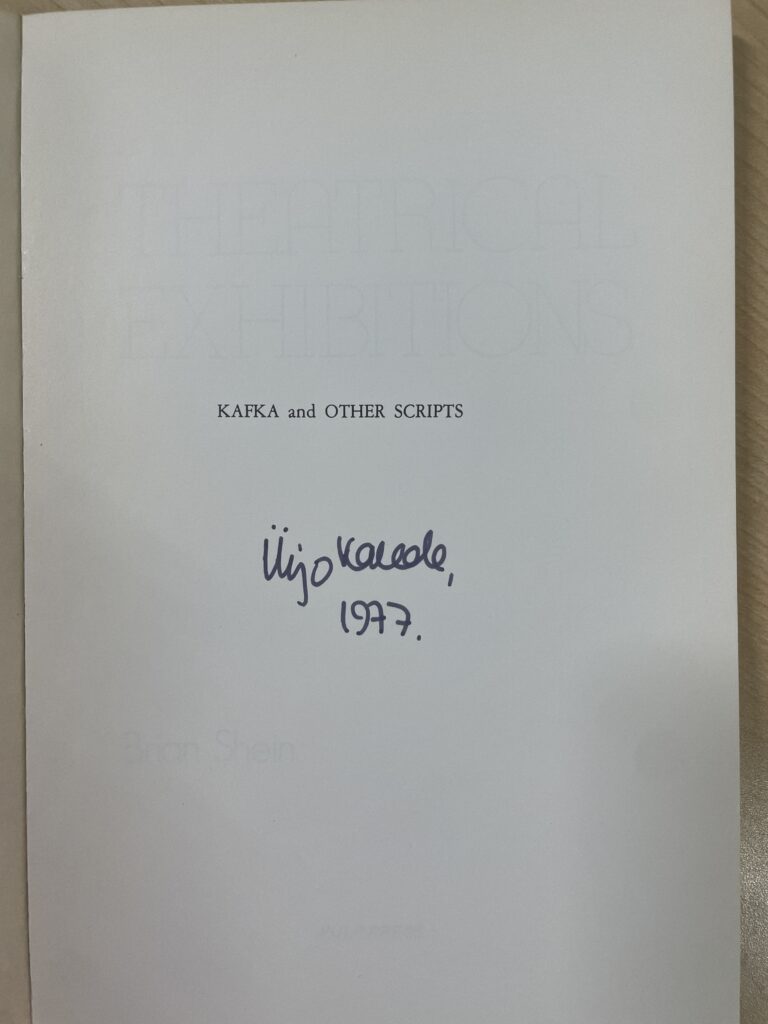

How could this giant of Canadian theatre be so gentle, disarming, terrifying? The terror of course being that he could see through my bullshit. There was a sign outside his small office door that read, “no whining.” A beginner playwright who had disagreed with his notes had written him a letter which read, “Fuck you, Mr. Kareda.” Inside his office the letter was framed. Also inside his office I discovered Urjo’s personal copy of my father’s book of plays.

A year or so after the unit ended, Urjo died. Two nights after that, he visited me in a dream. In the dream we were hilariously in the waiting room of his dentist’s office, where my billing made perfect sense to me. He probably had to cancel his last supper with Margaret Atwood in order to slip in a quick goodbye with a baby playwright before his last teeth cleaning.

In the dream I told him about the ancient Celtic phrase for “soul friend,” Anam Cara — a friend who understands forgives and completely loves you. He had not only claimed my father but he’d also claimed me as a soul friend, and he was mine.

I say nothing. Even in dreams his presence is intimidating.

Comments