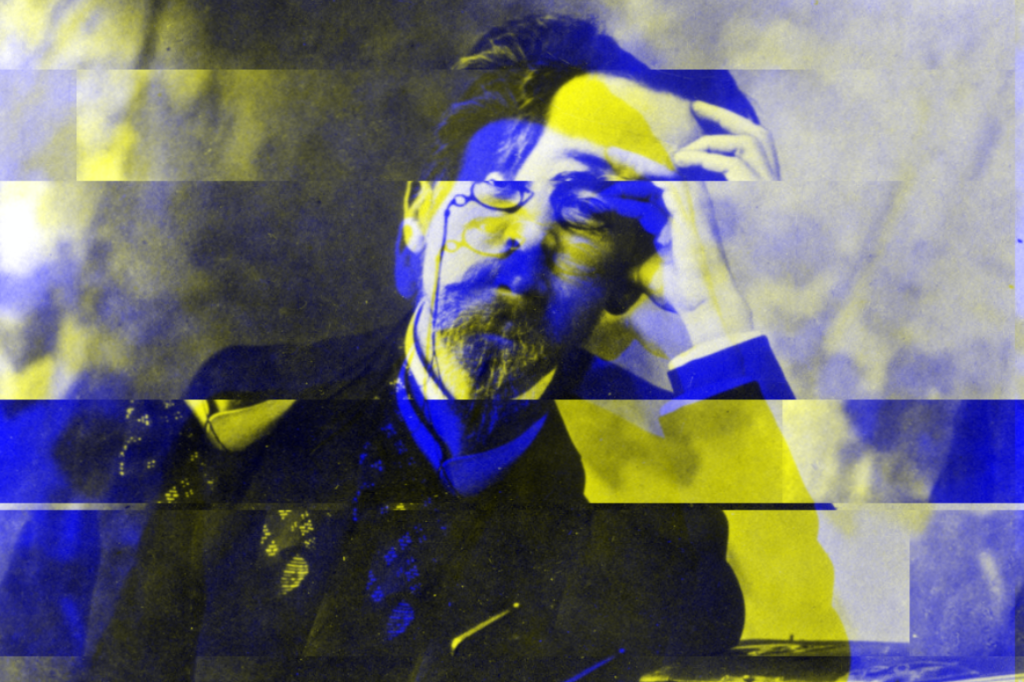

Why Is Canadian Theatre So Russian Right Now?

Content warning: this essay discusses collective trauma.

Why is Canadian theatre so Russian right now?

By the end of this season, Chekhov will have had at least four productions in Toronto. In the fall, Michel Tremblay paid tribute to the writer in Cher Tchekov at the National Arts Centre. I saw Bulgakov’s Le roman de monsieur de Molière staged at Théâtre du Nouveau Monde in November (an adaptation which, in quite the flight of fancy, depicted the writer of The Master and Margarita as pro-Ukrainian). Buddies in Bad Times put a call out for submissions this February inviting artists to playfully “filter Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s unique style and perspectives through a 21st century queer lens.”

As a Ukrainian-Canadian, I’ve asked myself: why, now, of all times, are we doing so much Russian work? Are we staging it more than we were prior to the full-scale invasion of Ukraine one year ago? And if not more, why isn’t it less? The Russianness of our theatre this past year has been striking to me — almost as striking as the near-absence of Ukrainian stories on our stages in as many months, especially in Toronto.

I’m curating a Ukrainian play reading series for the Stratford Festival slated for September. I developed this idea with them as I struggled with how little our theatres seemed to be engaging with the genocidal war unfolding before everyone’s very eyes. I had initially chalked this up to whataboutism (“what’s happening in Ukraine is awful, but what about the other awful things in the world?”), which so often leads to sitting on one’s hands about everything. But then I came to see how academic institutions and theatres in the UK have rallied madly to commission and translate Ukrainian playwrights and get readings — even productions — on their feet. The Metropolitan Opera in New York dedicated the remainder of their 2022 season to “Ukraine, its brave leaders, citizens, and artists;” a New York theatre company has programmed one of my just-finished plays for an annual festival of theirs. Director and translator John Friedman’s highly successful Worldwide Ukrainian Play Readings initiative has had 74 affiliated theatre events in the States since March 2022, 47 in the UK, and 43 in Germany.

To date, Canada has had three.

Canada boasts the second largest Ukrainian diaspora in the world — second only to Russia, in fact. Why hasn’t this diaspora been met by our theatre scene in what is arguably its greatest moment of need?

I’ve been having conversations with fellow artistic directors about what may be going on and whether or not something should be done about it. I personally don’t think that it’s the theatre’s imperative to address all the injustices and redress all the harms in the world — in fact, I could argue that this is in no way theatre’s responsibility. That said, I believe that it’s in theatre’s essence to engage with the Now. It’s what plays do in the liveness of the theatre, us gathering in shared space and time.

Canada boasts the second largest Ukrainian diaspora in the world — second only to Russia, in fact. Why hasn’t this diaspora been met by our theatre scene in what is arguably its greatest moment of need?

My recently workshopped play The Division opens with:

Plays when performed, happen in the Now. Inescapably so. And although the piece you’re about to watch plays with time, it never wrenches itself from the Now. It simply can’t. It bears acknowledging that part of the Now we find ourselves in includes an illegal and unprovoked full-scale invasion of a sovereign state by its neighbour.

I ask this sincerely: is the genocide in Ukraine less a part of our Now than in places like England and the U.S.? If that’s true, how do we feel about that? Do we want to change that?

In a number of substantive ways, Chekhov speaks to our Now. His dramatization of longing and the passage of time may be precisely what many post-lockdown, pandemic-emerging artists and publics want to sit with. The vast inner worlds of his characters, walled up with their existential thoughts and dis-ease, may feel utterly current.

But when it comes to the words and worlds of Russian writers, the Now holds more. Ukrainians are worth listening to on this matter.

The Drama Theatre in the Ukrainian city of Mariupol that was infamously bombed in March 2022 — the one that had thousands of civilians taking shelter within it and the word CHILDREN scrawled in massive letters on its front lawns to alert warplanes — is now encased in construction fencing put up by the Russian occupiers. The enormous barrier is being used to obscure the demolition of a theatre which, according to Ukrainian authorities, contains the bodies of at least three hundred of those who died in the air bombardment. Some estimate the death toll closer to 600. A number of those bodies belonged to theatre people who took refuge at their former place of work and play.

But this fence is doing more than masking a war crime. Because the Russians have covered it in massive banners depicting Pushkin, Tolstoy, and Gogol. These writers aren’t around to endorse the genocide, but they’re part of its narrative nonetheless. And the narrative of Now.

The Russianness of our theatre this past year has been striking to me — almost as striking as the near-absence of Ukrainian stories on our stages in as many months, especially in Toronto.

I know that we don’t want Russian literary figures to get dragged into this thing. And I’m starting to think that in Canada we don’t see how they can be. I’ve come to wonder if we’ve actually ceased to think of artists like Chekhov and Dostoyevsky as Russian writers. We just think of them as ours.

David Mamet holds no shortage of problematic political views, but among them is one we appear to embody without question. It surfaces in the intro to his published adaption of The Cherry Orchard:

Why do we cherish the play? Because it is about the struggle between the Old Values of the Russian Aristocracy and their loosening grasp on power? I think not…The enduring draw of The Cherry Orchard is not that it is set in a dying Czarist Russia or that it has rich folks and poor folks. We are drawn to the play because it speaks to our subconscious – which is what a play should do.

We have deemed the cultural context and dimensions of Chekhov as not terribly relevant. Chekhov has become a man of no country. Or perhaps, more generously, of all countries. And so his plays are not Russia and Russians: they are action, character, metaphor. Something of this appeals to the artist in me, art as borderless.

But the me of the last year knows especially well that this placelessness is false.

What I’ve come to experience — this will not be news to folks in the theatre sector — is that metaphors play out differently depending on the body you’re in, the relationships you’re a part of, and the communities you’re engaged with. For some of us, Chekhov is inextricably a Russian writer no matter how much folks wish otherwise. And Russia can never be just a metaphor when it’s a place, people and culture in the Now bent on subsuming another. While we may delight in how something speaks to our subconscious, are we failing to be conscious?

When it comes to what we’re putting on our stages, I crave a conversation. In a recent phone call with an esteemed colleague, I was asked: “can you tell me about the harm of staging Russian work right now?”

It’s a good question.

I could respond macroscopically, and say Russian cultural imperialism is a thing, and if we aspire to be an artform that’s part of a greater decolonizing project, then we have to examine all forms of dominant culture, all forms of subjugation and erasure, and respond according to our values. Russian culture casts a shadow from which other cultures cannot emerge without a collective effort. At this time, when our liberal international order is collapsing at the hands of a tyrant and Ukrainians and Ukrainian culture are being systematically eradicated, engagement with Russian voices is consequential. Even the voices of Russia’s past.

But I want to answer the question of harm from a more personal place. A place harder for me to square.

In the past year, I’ve been living with a constant, low-grade grief and varying levels of anxiety. More than ever before in my life. Grief and anxiety are fairly common, as it turns out — and many friends and colleagues of all backgrounds have been able to relate, commiserate, apply some balm. Some have given me some cedar to burn.

But there’s one thing I grapple with on a daily basis, a thing I’m profoundly ashamed of, that prior to February 24, 2022 was not a steady psycho-emotional companion of mine: hatred. I am an artist who carries hatred. And I work tremendously hard to tuck it away and metabolize it, day after day. I channel it into activism. Into writing. Into anything.

I know why it’s there and why it keeps coming back. It only takes a Telegram message from a friend: “three days without water already,” and a photo of him drawing water from a creek. “For technical use.”

I ask what he means by this. “To take a ‘bath’ and to flush the toilet. Line for drinkable water too long.”

It only takes a line or two in The New York Times: “Russia has relocated 6,000 Ukrainian children to camps…children as young as four months old are being held in ‘integration programs’ designed to Russify them.”

There it is.

At this time, when our liberal order is collapsing at the hands of a tyrant and Ukrainians and Ukrainian culture are being systematically eradicated, engagement with Russian voices is consequential. Even the voices of Russia’s past.

But what does this have to do with the programming of a Chekhov? Objectively: absolutely nothing. But I have to work hard to separate the matters, and the madness of it. I have to remind myself that a theatre in Canada blithely programming a Russian writer as before is not putting up a fence bannered in Russian Greatness to obscure and rationalize war crimes. The conflation is irrational; even unfair. But is it understandable? Am I having a human response? Or a monstrous one? And is it useful, if nothing else, to make it known?

When we program and explore Russian stories — for as much as we can call them ours, they are not in fact detachable from either a Russian origin or a contemporary imperialist enterprise — I’d like to know we’ve considered the myriad casualties of genocidal violence, which is to include the folks who live really nearby, the neighbourhoods and communities our theatres seek to reflect or at least relate to. For what it’s worth: since the start of 2022, more than 158,000 Ukrainian nationals have come to Canada to join an existing diasporic community of over 1.36 million.

I will articulate in no uncertain terms: I don’t want us to cancel Russian culture. I don’t think we can, actually — it would amount to cancelling deep parts of ourselves and our artform. But there are alternatives. As put in an interview with Ukrainian filmmaker Oleksiy Radynski: “Russian culture deserves a punishment more severe than a boycott. It deserves a deconstruction.”

It deserves a conversation.

For me, this is not only about taking the time and energy to scrutinize our own penchant for Russian work and its privileged place in our Canadian canon. It’s not just about being mindful of what it means to platform so-called “good Russian” voices at this historic moment. It’s about getting to know that truly distant other: the Ukrainian. An other we may be inadvertently distancing all the more through the choices we’re making.

I don’t think it’s as simple as swapping out a Russian bit of programming with a Ukrainian one when artists and audiences here are in a long relationship with Russian work. But our most resourced companies can surely start developing a relationship with the Ukrainian story.

I realize that it’s not apples-to-apples. I don’t think it’s as simple as swapping out a Russian bit of programming with a Ukrainian one when artists and audiences here are in a long relationship with Russian work. But our most resourced companies can surely start developing a relationship with the Ukrainian story.

A number of theatres — particularly in Western Canada — are presenting Punctuate! Theatre’s First Métis Man of Odesa in the coming weeks. I find this reassuring. But beyond presenting a small indie company that took the initiative, what more is being done? What more can we do? I can’t help but feel what an opportunity there is in the Now, to show up in wartime, to capitalize on the intimacy and power of the theatre to shift proximity, enliven empathy, and play a role against cultural erasure.

And if you want to stage your Chekhov in addition to that wartime effort, go for it, but then dare to stake what seems to be your claim: “Chekhov is not a Russian writer. Not Russia Now. We’ve annexed him as an act of defiance, as a radical act on the cultural front of this war.”

And then see what conversation follows.

Comments