Backwards and Forwards

“Queer is to dream, desire, and create new possibilities, most especially the possibilities that we’ve been systemically told are not possible. For this reason, queer is a noun, a verb, and an adjective — one that describes anti-normative aesthetics and ideologies.”

–Amber Dawn

One of my favourite books on theatre is Backwards and Forwards by David Ball. It’s a play-reading manual that asks you to look, step by step, at every moment in Hamlet and unveil what drives Hamlet forward, all the way to the end. Every action is made of two events that trigger another event, thus moving the plot forward. In this way of reading, theatre becomes a precise formula. The well-made play reigns supreme, and anything that isn’t “well-made,” so to speak, is not a play.

Mr. Ball loves to condescend the reader and lament the theft of his stamp collection. I find it comforting to have this old man tell me exactly how to create theatre—it suddenly seems easy. “Child’s play!” I chuckle to myself, lining up event after event, driving my plot forward. “Wow! I just LOVE writing! I’m not crying at all!” I say, writing glorious draft after glorious draft. Or at least, this is how Backwards and Forwards makes me feel my life should be, while in reality I’m crying in the bath at 6 p.m. on a Tuesday, wondering how the hell I roped myself into spending so much time staring at the ceiling, and not, in fact, writing.

I like thinking that everything can be “backwards and forwards,” but a lot of the time, when I’m writing, it just feels like a whole lot of backwards.

I am a queer playwright. Beyond my sexual identity and those of my characters, queerness permeates my work on a political level. I seek to work against hierarchies and methods of oppression that have been so ingrained in our creative culture. I’m always looking for the possibilities that we thought weren’t possible.

My work is about shining a light on what frightens me. Is it scary? Is it uncomfortable? Would I rather not talk to my grandfather about it? Then it is definitely going into a play. The thing is—a lot of what disturbs me in my life is subtle, and insidious. My work grapples with my own internalized misogyny. It looks at my unconscious racism. It deals with victim-silencing. It confronts the quiet forms of abuse that are pervasive in our communities. My creative process in itself acts as an unlearning: I am taking the time to challenge a system built on racial oppression, the naturalization of poverty, and misogyny. I am trying to create characters who are also going through that struggle. I don’t sit down and think to myself, well gee Rhiannon, how am I going to attack the patriarchy today? Or, if I do think that to myself occasionally, my characters definitely don’t. I create through the process of listening. I move backwards and that takes a very, very long time.

This unlearning, this questioning, is not only time-consuming, but very difficult to do when you don’t have any resources. In September of last year, I bought a grilled cheese sandwich and effectively bankrupted myself. The grilled cheese sandwich cost $4.50, leaving me with -$0.90 in my chequing account. I was working part-time so that I could write, but was also unable to write because I was constantly thinking about how close I was to having literally no money. My show Miranda & Dave Begin Again got into the Montreal Fringe Festival and I didn’t eat snacks for two months so I could afford the entry fee. I couldn’t pay to see shows because I was trying to create one. I value my artistic time immensely, but the anxiety of constantly being broke is a huge, scary burden. It drains all of your energies, creative and otherwise. It’s hard to unlearn systemic oppression while you’re spending all your free time patching together scraps of work to survive.

Now, a year later, I’m able to talk about my process clearly because I’ve spent the last eight months being supported by Nightswimming Theatre as a part of their 5×25 initiative for creators born in 1995. For me, 5×25 is a radical reimagining of what I can create in the theatre—what theatre is, and where interdisciplinarity comes into play. With this criteria, the possibilities become endless.

I’m a twenty-one-year-old working and living in Montreal, Quebec. (5×25 is open to anyone, anywhere in Canada. I get the good bagels, spiral staircases and low cost of living in Montreal, plus the second-hand glamour of working in Toronto.) When I applied for 5×25, I was in the process of dropping out of school at Concordia University. In my time in school, I discovered that I’m an unfortunate academic: I want to follow all of the rules perfectly, but I absolutely hate being told what to do (again, see my obsession with Backwards and Forwards). After a poetry professor bluntly asked me what the fuck I was doing at Concordia if I wanted to be a playwright (her words, not mine), I decided to drop out. My desire to excel was in constant competition with my desire for creative freedom.

The thing is, I still felt like a sham—I was experiencing full-on creative puberty. It’s like when you’re twelve and three quarters and dead-set on being a “cool teen” but when you turn thirteen, you realize that you’re just a slightly older twelve-year-old. You’re like, “I’m a teen!!!” but everyone knows that you’re not really a teen until you’re like twenty-five. I was going to drop out of school to pursue my career as a “cool playwright,” but that also felt like a lie. My parents were nervous, I was nervous, and every time I said the word “playwright” my mouth started to taste all ashy, like false, flakey dreams. In the words of an aggressive cab driver I had a couple of weeks ago, “Everyone knows that only old gay men are playwrights.” I couldn’t be telling the truth.

If you’re a ’95 baby, you’re probably not even emerging in the eyes of institutional gatekeepers. Maybe you’re crowning… Maybe you’re stuck in the womb holding on for dear artistic life. The point is, there are tons of other artists out there with you. They all remember being frighteningly green and uncertain about their artistic credibility. I’m not the only person who has felt like a fraud. Even Governor General’s Award–winning playwright and kick-ass feminist Erin Shields said she first felt like a writer “When Denise Clarke told me (and everyone else at the One Yellow Rabbit intensive in 2001) that we weren’t impostors. That we were artists. I was like, really?! Fuck yah!… A transformative moment I think about often.”

When I applied to 5×25 last November, I had written and performed in a twenty-minute play that was as foetal as my creative process. I had done the Artist Mentorship Program with Black Theatre Workshop. Aside from that, I didn’t have much to show. But I made a conscious choice (with the help of a bit of wine) to push my imposter syndrome aside. I dubbed myself “baby playwright.” (It was in my Twitter bio and everything.) While I didn’t have a body of work to back me up, I did have a plethora of terrifying ideas.

My initial application idea was a whole show about blood—something about free-bleeding while screaming at the audience and riding a stationary bike. The plan was to line up my periods with the lunar cycles and ritually perform the show on the full moon. I would like to say that this is 100 percent a joke, but in the summer of 2015 it was a definite possibility. I’m letting you in on this so that when my show is somewhere, one day, together we can see how far a year of thought can take a concept.

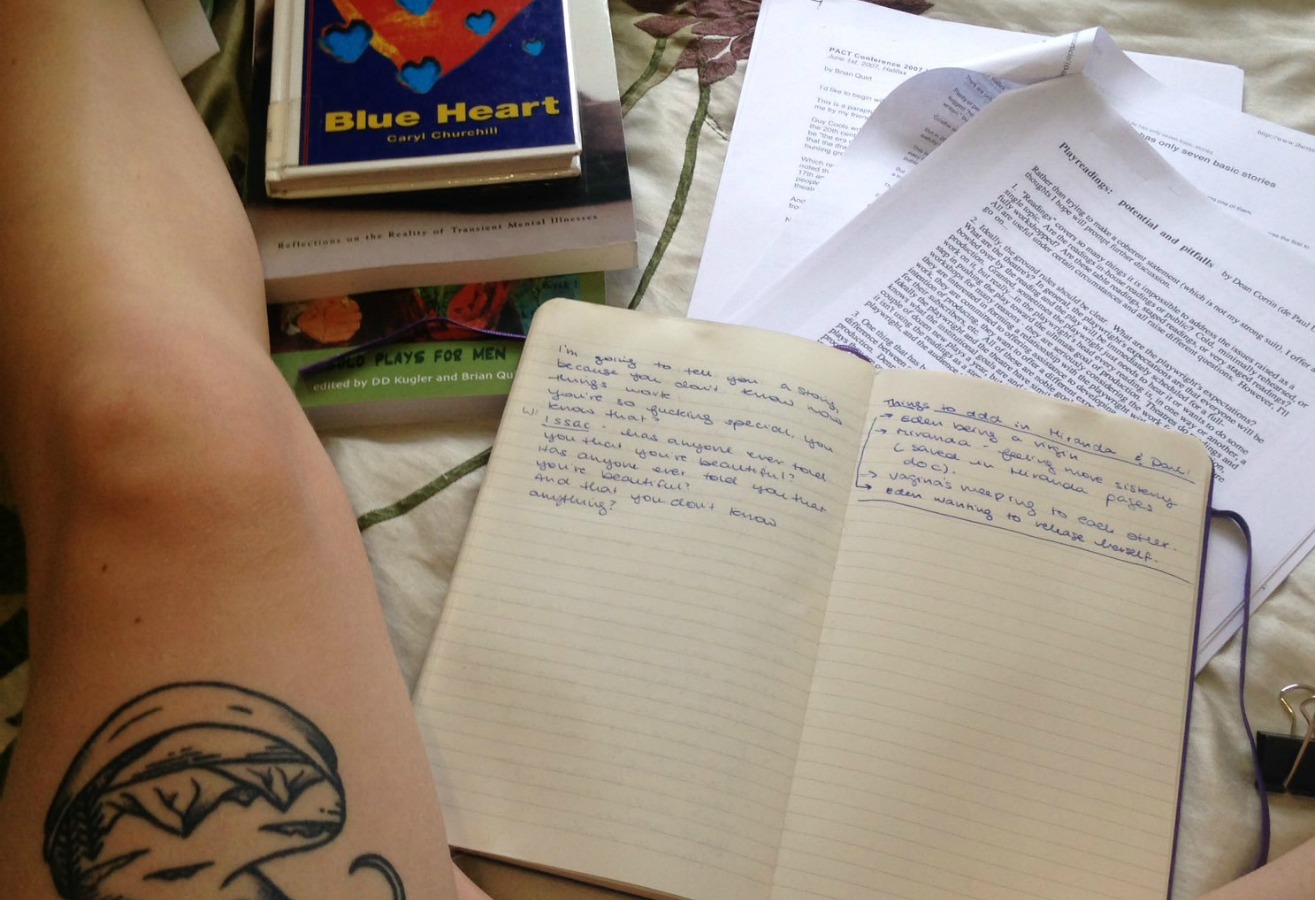

Now Wasp, my play in development with Nightswimming, has completely changed. Even in just the last few weeks, the entire thing has shifted. Isaac is an auto mechanic. Jayne is mysteriously pregnant. Wasp is fighting for her body’s autonomy. They arrive at midnight on the winter solstice in the ruins of an old church. They’re there to perform an abortion.

At this point, I’ve cut out the bicycles, I’ve cut out the free-bleeding, I’ve cut out the moon—though while writing this I’ve decided to add it back in because, heck, I love the moon. (The moon is high on the evening of the winter solstice.)

Even though my ideas are constantly shifting, what’s stuck with me through this process of discernment is the idea of ritual. How do we perform events over and over in our lives? What rituals have been handed down to us from our communities? What rituals do we no longer accept or need? All these are questions I’m exploring in Wasp. These questions are also the reason I am so drawn to the theatre—where else do we get to both perform and undo our culture’s rituals? I like Backwards and Forwards because it’s a guidebook on how to create a ritual that effectively tells the story of people like Hamlet. The thing is, I’m not interested in Hamlet. I’m interested in Ophelia, who gets murdered offstage by the well-made play. Her story doesn’t fit in the roadmap. How do I use the well-made play structure as a tool in feminist theatre? How do I subvert it? How do I create something new and exciting and POWERFUL if I always feel like I’m moving backwards and backwards against everything I have been taught in my twenty-one years on earth? These are my questions as I attempt to queer my creative process and the theatre I am putting out into the world.

5×25 is about looking for the possibilities that we, as young people, are told aren’t possible (because of lack of experience, because of lack of resources, because of lack of accessibility) and making it happen. I’m here to tell you that you’re not an impostor, that in fact, you’re an artist. You might be a very young and occasionally lost artist, but the resources are there. You don’t need a body of work behind you. You don’t need a resume. You don’t need approval from the gatekeepers of your artistic community. The work is waiting to be done.

Rhiannon Collett’s play There Are No Rats in Alberta is on February 23 – 24 as part of the Rhubarb Festival. For tickets or more information, click here.

Comments