A Kind of Painful Abundance: Andrea Donaldson Talks Big Scars and Big Love in Pinter’s Betrayal

There are some lines in the play that agitate contemporary sensibilities,” says director Andrea Donaldson of Betrayal, the upcoming production of which marks her Soulpepper directorial debut. “But it’s fun to think of these lines through a contemporary lens, and through a feminist lens I can’t help but bring.” Written by celebrated English playwright Harold Pinter, Betrayal revolves around an affluent London couple, detailing the extra marital affair between Emma and her husband Robert’s best friend Jerry.

Typically known for directing contemporary feminist works, Donaldson insists the interplay of love and betrayal keep this work as relevant today as it was four decades ago. “The play begins in 1977 and ends in 1968, so it leads us a-chronologically back through time. Pinter set it in the time he was writing it. I wanted to keep it within that time. There’s something really fun about it existing in this separate space from us, and embracing playing in a different era, in the location of London. It feels like it kind of operates in this little bubble that we get to observe that we are separate from.”

Jordan Pettle, Ryan Hollyman, and Virgilia Griffith in Betrayal. Photo by Dahlia Katz.

At the time of Betrayal’s penning, polyamory and extramarital affairs were not topics that had permeated within the zeitgeist as they have today. To describe the work as being ahead of its time is no misnomer, but Donaldson clarifies, “Because of our contemporary perspective, that might come into play, but I don’t think of this as an open marriage. There is something that’s really fascinating for me in terms of the character of Emma, who is written as a woman who is quite actively seeking out this relationship with her husband’s best friend. It does feel ahead of its time in the sense of writing a female character that is in touch with her own female agency. That’s come up for me, Virgilia Griffith (Emma) and all of the team in conversation; we have a male playwright writing this play in the 70s, about this relationship that takes place in the 60s and 70s. So in acknowledging the era that it’s set in, we’re embracing the kind of social mores of that time, and that includes a specific perspective on what a male-female hetero relationship is.”

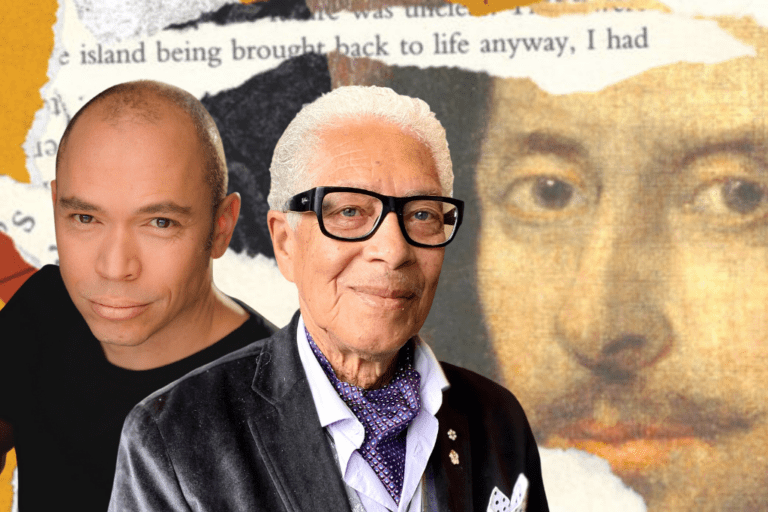

Power and class play huge parts in Betrayal, and even more so in this particular production. Emma is played by a black woman (Griffith) and Jerry is played by Jordan Pettle, a Jewish man. The portrayal of interracial relationships was very rare at the time, and though the original text hasn’t been modified to address the new dynamics introduced by the ethnicities of the lead actors, the theme of both characters being outsiders rings ever true.

“This couple who is sort of a power couple, and who situate themselves with all the poise and sophistication of their literary world; she runs a gallery by the end of the 70s in the play. They seem from the outside to live by the rules, but they have this ‘us against the world’ logic.”

The rebel mindset is something Donaldson is familiar with: “I famously only direct women playwrights,” she laughs.

While said in jest, Donaldson’s directing credits demonstrate a certain truth. “Most of the work that I’ve been invested in during my career has been developing new plays, and very often developing female voices. As the artistic director for Nightwood Theatre, I have a real love and agenda for bringing voices to the stage that have been underrepresented and undervalued. So it’s not quite a vacation for me, whatever I work on I bring my perspective to. I can’t help but do that. It’s fun to be directing the words of someone who isn’t in the room. I can research them, but I can’t actually converse with them, or deliberate with them. I can’t ask them for a rewrite. With a new playwright, we’re working together to figure out what gaps need to be filled. With a playwright who is no longer with us, we take what they say as truth.”

Ryan Hollyman and Jordan Pettle in Betrayal. Photo by Dahlia Katz.

With nobody to mansplain the play’s feminist themes, it becomes clear why Donaldson would be drawn to the work, despite Pinter’s male point-of-view. “It fascinates me, in my research, that the playwrights Pinter looks to in his context, that he looks to as his masters and mentors; they’re all men. All of them. There’s not a single female playwright—of course—that’s listed. It’s interesting to be looking at a play that is so steeped in a tradition of maleness. There are some lines in the play that agitate contemporary sensibilities. But it’s fun to think of these lines through a contemporary lens, and through a feminist lens I can’t help but bring.”

Typically, the roles of “wife” and “lover” function to serve the male characters in a story. Emma remains central to this story, and is not a victim of her relationships. “She’s actually at the core of all the decision-making about them. She’s remarkably ruthless in a way that is really rare in female depictions, certainly by a man.”

The play also acts as a puzzle. “We’re talking about people who are betraying each other, so there’s a lot of lies that come out. As a creative team, we need to build up a firm understanding of what’s true and what’s false, and when people knew what they knew, because that’s part of the betrayal. It forces us to be clear in our bones about where some of the lies began to happen, and what people know in each scene, and then put it back together chronologically. For example, we had to figure out how to go from a break up in one scene, to running into their lovers’ arms in the next scene three years ago when things were very blissful. From the actor’s perspective [it’s about] being able to—instead of building emotional scar tissue that happens throughout a play—undoing scar tissue to get back to the past, before things went sideways.”

Virgilia Griffith and Jordan Pettle in Betrayal. Photo by Dahlia Katz.

All this asks the questions; of the many, which betrayal is worse? There are numerous parallel betrayals happening, some of which certain characters don’t know until the very end of 1977 (chronologically the last year in the play). “I don’t think there’s necessarily an answer to this. In a certain moment I might feel a different way,” Donaldson says. “In one moment, I might feel that the friend betrayal was worse than marital betrayal. Or in fact that the betrayal of knowing something and not telling someone can be a bigger betrayal than sexual betrayal. By the end of the play there are some major rifts that happen, that I don’t know if we can ever come back from.”

Yet for a betrayal to mean anything, there needs to be some level of trust, and love that has been compromised. A pessimistic interpretation of these characters would be that none of them really love each other. But Donaldson disagrees: “I think there’s a very big love [amongst the characters]. In some stories about affairs that you see onstage, TV, or in movies, there’s this kind of cliché around why people have affairs. That there’s this certain kind of lack, and an affair is there to fill the void of something that is missing. Maybe for some people that’s true, and that’s why it is a cliché. That might be true for Robert and his wife that we never meet. But certainly, for Emma and Jerry, I don’t think that their sexual life has gone limp, or that they’re necessarily bored, I just think that they’re brilliant. I think that they’re kind of estranged geniuses that need more from life, and part of that is creating complications. Emma’s leading two entirely separate lives, except that their contingent upon each other. The relationship with Robert at a certain point can only exist if Jerry’s there on the other side, and vice versa. So I don’t think it’s necessarily a kind of lack, I think it’s a desire for a certain kind of painful abundance.”

Virgilia Griffith and Ryan Hollyman in Betrayal. Photo by Dahlia Katz.

With Betrayal and her Soulpepper directorial debut around the corner, Donaldson concedes that the transition to a larger platform from indie theatre often comes with added pressure and expectations—all of which can run the risk of restricting the creative process. But Donaldson’s experience has been different. “In terms of feeling bound by anything, I don’t, to be honest. As an artist you have to trust that when you’re hired by anyone, or brought on to collaborate with anyone, that what they’re hiring you for is your ethics, your integrity, and your vision. As artists, by virtue of how everybody works, we’re always going between small budgets and big budgets. I feel really grateful to have the technical power of this place behind the choices I’m making, it’s great to be working with some of the very best. As an indie artist you’re doing that too, it’s just a little scrappier.”

Comments