How Vivek Shraya Keeps Getting Her Groove Back

“I remember watching the movie The Bodyguard, and hearing Whitney Houston’s voice as a kid and being like, what is this voice?” The awe in Vivek Shraya’s voice still bursts through, though she’s reflecting on an experience from decades ago. “That opened me up to pop music more broadly.”

Pop music might not be what Shraya, a Calgary-based powerhouse of Canadian arts, is primarily known for. But a fascination with pop culture and music is what drew her into the scene. Though she’s mostly spoken about as a writer—having published popular books like her poetry collection Even This Page is White, queer fable She of the Mountains, and the widely-acclaimed single-essay book I’m Afraid of Men—her interest in music has been channeled into multiple projects. The 2018 album Angry from the musical duo, Too Attached, she formed with her brother was praised by the CBC as “one of Canada’s most inclusive, galvanizing, and radical albums”; her album Part-Time Woman with the Queer Songbook Orchestra was long-listed for the Polaris Prize.

Recently, Shraya has been thinking up ways to integrate these different aspects of her creative career. In her upcoming novel The Subtweet, music becomes central, as the novel focuses on the trials and tribulations of being brown and female musicians in the contemporary industry. It also features an accompanying soundtrack, with all the songs written and performed by Shraya. Simultaneously, she’s finally making her first foray into theatre, after circling tentatively around it for many years, with a solo-production feature integrating music, memoir, and fiction: How to Fail as a Popstar, a Canadian Stage-commissioned world premiere.

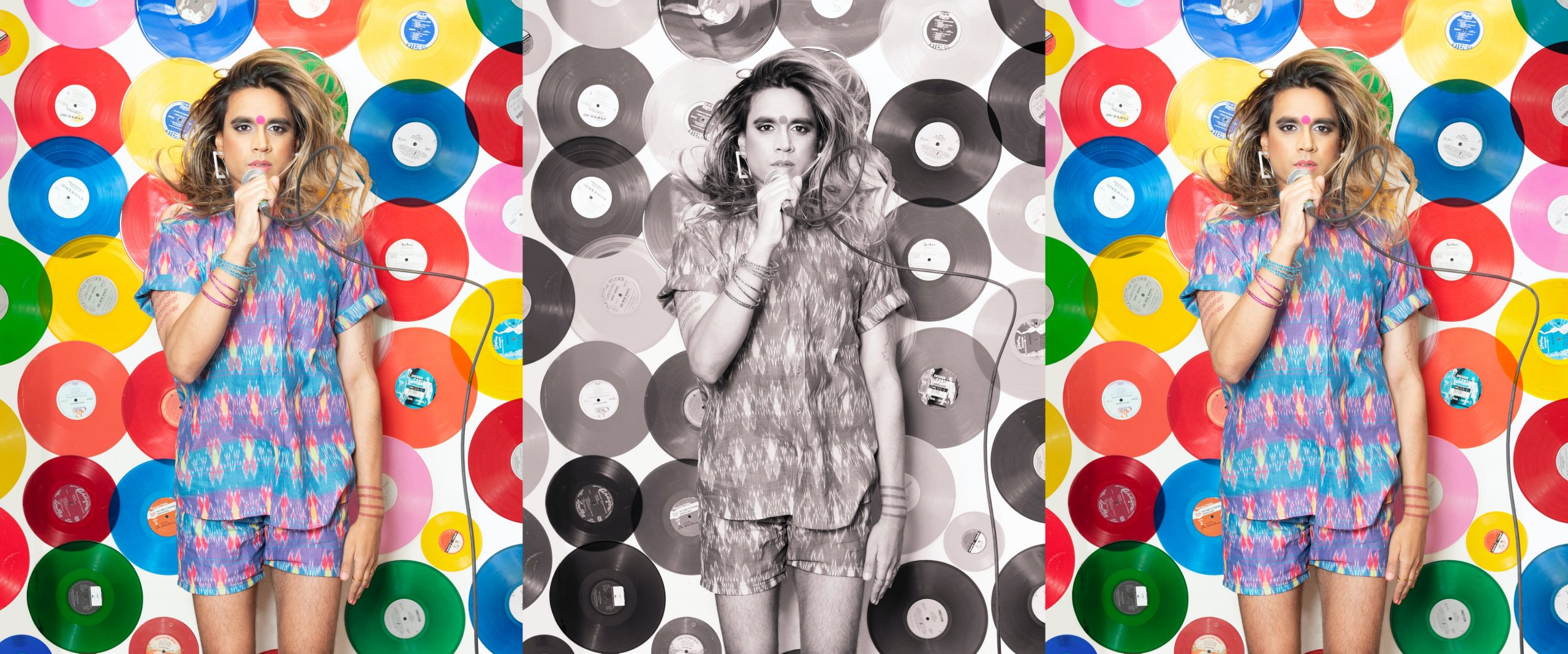

Photo of Vivek Shraya by Heather Saitz

What led Shraya to finally take the plunge? “A play called Express Yourself that ran in Toronto’s Summerworks Festival with Liz Peterson, that’s what I sort of saw as a calling to theatre,” she says of the impetus to break into the medium. “It was a play that includes a whole lot of the things that I do when I do a reading, typically from a book, but in a more theatrical context.”

Several years later, the idea for How to Fail as a Popstar came to her while studying music biographies for research on The Subtweet. She fell in love with the beautiful format of the genre and the quaint narrative structure that it follows—but realized that the creation of a music biography is contingent upon the grandiose success of the musician in question. “I was like, how would I tell a story of failure? How would I tell an anti-music biography narrative, or an anti-success story?”

Though cheeky and somewhat lighthearted, the idea carries a deeper criticism of our cultural climate at its heart. Shraya believes that in our current social and economic climate, we put a lot of emphasis and attention towards success narratives. For her, How to Fail as a Popstar is an opportunity to honour her failure for its own sake, and to invite those that see it to do the same with their own failures—an exploration that’s not contingent on seeing the failure as a stepping-stone to new success.

The conceptualization of Shraya as a failed artist doesn’t come naturally. She’s an energized, intelligent artist with a long and varied career. She broke into mainstream success in 2018 with I’m Afraid of Men, which was listed as one of the best books of the year by Apple and the Globe and Mail, featured in Vanity Fair, referred to as essential by Bustle, and was a finalist for the Lambda Literary Award. And writing stories and songs aren’t the only tricks she has up her bedazzled sleeves—she’s also created two political photo series, Trisha and Trauma Clown; a short animation about community called Reviving the Roost; and teaches at the University of Calgary.

“Vivek is one of the most clear-eyed visionary artists that I’ve worked with… You get the sense in speaking with her that whatever project she has dreamt up will see the light of day,” says Shaun Brodie of the Queer Songbook Orchestra. Others who have worked with Shraya in the past have a similar opinion of her clarity of mind and dynamism. “Vivek comes to a project with a real sense of what she wants,” says Zachary Ayotte, the photographer who worked with her on Trauma Clown and She of the Mountains.

Vivek featured in the M.A.C. Originals campaign, 2019

Even Brendan Healy, artistic director of Canadian Stage and director for How to Fail as a Popstar, has trouble connecting the dots between Shraya and failure: “I was struck by how completely open and adaptable Vivek is. She is endlessly adventurous and committed to being good at everything that she does.”

But the tendencies we might have to cast artists and celebrities into simplified, unnuanced roles is an issue. Though the inclination to think of celebrities in reductive ways that either idolize or demonize them has been going on since the inception of consumable media, Shraya thinks it has been accelerated by how we as a culture engage with social medias. She notes that, because her social media posts often feature a glamourized and enthusiastic version of herself, people tend to see her as an optimistic, happy-go-lucky woman. “But you actually just don’t know what’s going on inside. I think we need to be conscious of that more broadly,” Shraya says.

How to Fail as a Popstar is partly her trying to break from the role of accomplished trans artist she’s been cast in—to own the complex and contradictory nature of who she is as a person and artist. That reclamation involves attempting to integrate her failings, a job that might not be as cathartic or liberating as it may seem to an outsider.

After getting the chance to begin workshopping the play in front of an audience, Shraya began to realize just how difficult of a task it was that she’d set out for herself. Being able to get up on a stage and speak at length about a difficult part of your life seems like something that can only be done after radical reconciliation; but to the contrary, Shraya confesses that she hasn’t really reconciled her failure as a popstar. “Towards the end I find it very, very emotional to push through. I have to deep-breathe through the whole thing,” she admits, speaking to how difficult and even humiliating the play feels at times.

Vivek’s teenage bedroom, Edmonton, age 18

Despite the pain and difficulty the play causes her, she still believes in what it allows her to do—to honour, grieve and mourn her failure. Performing this play gives her space to stand face to face against something that she doesn’t think will ever be reconciled, but which still requires acknowledgment.

Though this is her first foray into theatre, it’s not necessarily held apart from the remainder of her oeuvre. Zachary Ayotte notes that, “In spite of working across a variety of mediums, she is building something cohesive and complicated.” The disparity of Shraya’s work often winds through a set of similar themes and ideas. Fans of hers will notice a coherency of feeling between her projects.

“My mom is somebody who comes up a lot in my work; she’s kind of the hero in my life and my art,” Shraya notes about the things that guide her creative processes. Her mom comes up most explicitly in the photo series Trisha, where Vivek recreates old photos of her mom, posing in her place. It’s named after what her parents would have called Vivek if she had been assigned female at birth.

Though she isn’t involved with any religion, and doesn’t necessarily believe, Shraya also acknowledges that the spiritual, and a belief in something bigger, is an idea that resurfaces in her work a lot. “I grew up in a religious organization with a guru, and the kind of Hinduism I grew up in allowed for my gender creativity to not be seen as abnormal, because of the ways that Hindu gods transgress North American ideas of masculinity,” she says. Most viscerally, Hinduism is confronted in her book She of the Mountains, which fictionalizes the story of her youth by interweaving it with a story of the deities Parvati, Shiva, and Ganesh.

It’s also undeniable that much of Shraya’s work is very political, illuminating and confronting difficult social realities like racism, sexism, misogyny, and homophobia. Shraya made this artistic choice because of a sense of responsibility she claims she feels, to use the platform she’s been given to increase awareness, alter perspectives, and attempt to reach community members who might feel misunderstood or isolated.

An early gig, Edmonton, age 20

How to Fail as a Popstar continues along the paths Shraya has been constructing with her previous projects, integrating similar ideas and themes; the difference with theatre, she claims, is the length of the work. This play is 75 minutes long—a substantial difference when comparied to watching her read poems for a quarter of an hour, or an animation for a few minutes. She’s interested in what it means for an audience to stay immersed in a particular narrative for that length of them. And figuring out how to adjust to this medium was a bit of a challenge for her.

Pivoting to performing in a theatrical context, from teaching in Calgary and writing non-fiction, took a bit of recalibration, Shraya professes. Something that director Brendan Healy said to her stuck with her throughout the process—the old ‘show, don’t tell’ adage. “Often what makes theatre the most compelling are the things that aren’t said on stage,” she asserts; “trying to get the audience to think about what you’re saying without saying it.”

Often, the kind of works from trans and racialized artists that are compelling are those grounded in vulnerability and pain. There are pressures from creative industries and audiences for us to continue to recreate these narratives for an audience that’s transfixed by our pain. Shraya delved into this idea with her photo series Trauma Clown, in which, made up like a clown, she poses for the various traumatic roles that audiences have come to clamour for from her.

A year after that project, the idea of performing a play that opens up wounds for audiences yet again might sound contradictory. But Shraya insists there’s an internal logic to it. “It’s about the artists having the right to choose what we’re making, as opposed to industry telling us what to make; it goes back to who’s telling the story and why,” she points out. Followers of her work might be reminded of Death Threat, a graphic novel she created with Toronto artist Ness Lee in 2017. The book was a creative and depthful look at a traumatic experience she had with a transphobe who sent her malicious messages; but she had control over the creation of it, and wrote it because she wanted to and voluntarily chose to. She argues that How to Fail as a Popstar is a similar experience.

On route to a gig, Toronto, age 23

As an artist who’s a transgender woman, there are specific, gendered pressures for her to create work that expounds vulnerable and painful narratives involving transition and transness. Those searching for such a story won’t find it in How to Fail as a Popstar. “There’s deliberately no mention of transition; for some people this will be the first time that they, to their knowledge, are encountering a trans person onstage, and I find that people get very distracted by that kind of thing,” Shraya explains.

Shraya isn’t ashamed of being transgender, but she recognizes that cisgender audiences find it difficult to acknowledge transness without being fixated on it. And at this point in time, she yearns to tell different stories, stories without transness as the central focus. She points to Melina Matsoukas’ 2019 film Queen and Slim as a pop culture moment that grabbed her attention—in the film, transgender actress Indya Moore plays a character whose transness isn’t explicitly mentioned. “I think there’s so much pressure on trans people to represent our people and to be a voice. And I think that those things are so important, but it’s a burden in some ways,” she divulges.

Shraya recognizes that in some ways this is a problem with the arts industry in general, however. Though transgender people are starting to see some representation in mainstream media, things still need to change so that transgender artists can start to tell the stories they want to, as opposed to the same narratives we’re forced to tell, narratives that usually have transition or transphobia as their central focus.

In pushing to create art that has less of an explicit focus on herself as a transgender woman, Shraya may be starting to make gains, however slight. Her novel The Subtweet, being released in early 2020, is notable for its lack of explicit mention of transness; “I was really curious about that challenge of creating a novel with trans characters that isn’t about transness explicitly. The Subtweet for me in a lot of ways is a fantasy; I wanted to create something where the characters are trans and you either see it or you don’t, but the choice not to is your own,” she explains.

Photo of Vivek Shraya by Heather Saitz

In trying to diversify the stories that audiences will accept and receive from transgender people, Shraya believes that owning the specificity of who you are is one of the most important things one can do as a transgender person. Because of how we are often rendered invisible or silenced, a monolith of transgender experience has come into existence—owning the uniqueness of one’s own stories is a useful counter to this idea that all transgender people are a particular way.

Her work with Brendan Healy and Canadian Stage on How to Fail as a Popstar has been advantageous for her in taking back the specificity of her story. “One of the things I love about the play is that it doesn’t try to be universal, it’s actually quite specific to my experience,” Shraya happily recounts.

However, fans of her work who are interested to see where she follows these threads might have to be patient for a while. “I’ve had to retrain my brain a little bit because I’m realizing how much I’m a bit of a capitalist bunny, and I really bought into sort of ‘what’s next, what’s next,’ as opposed to really staying in the moment,” she admits. “I will say that I’m really loving theatre and I’d be curious what the experience would be like to play a role that isn’t based on me or coming from me. But overall, I’m really trying to sit in the experiences that theatre is giving and really enjoy it.”

How to Fail as a Popstar, a Canadian Stage-commissioned world premiere, runs February 18 to March 1 at the Berkeley Street Upstairs Theatre (26 Berkeley St.). For more information and tickets, click here.

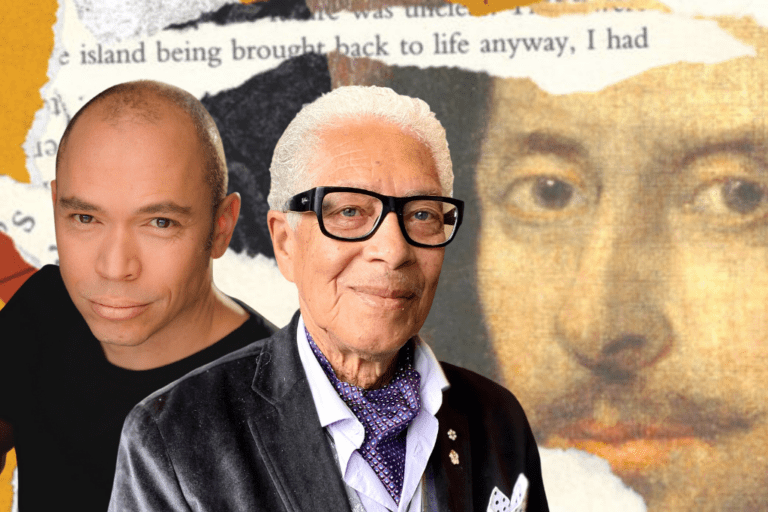

Photos courtesy of Canadian Stage and Vivek Shraya.

Comments