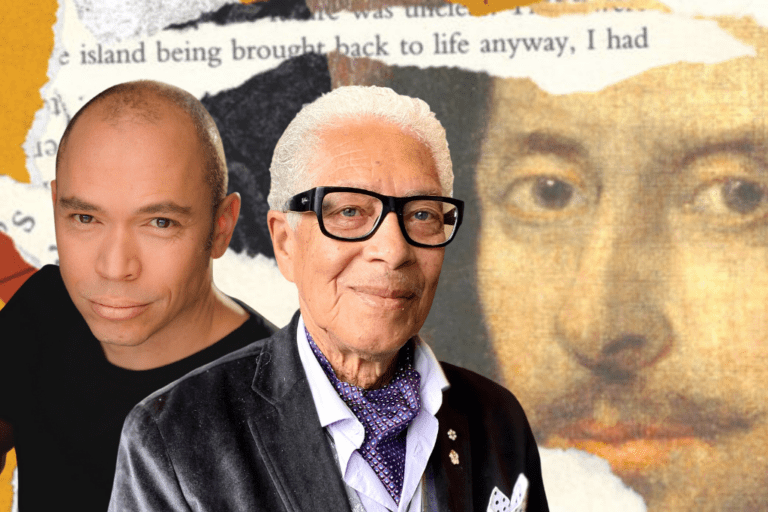

Spotlight: Alan Dilworth

Alan Dilworth is on a journey. An educator who became an actor who became a writer who became a director who became an artistic director, he articulates his relationship to theatre as one of continual discovery.

While such a description might evoke restlessness, this is not the vibe he gives off nor what his close colleagues say is notable about him. Rather, Dilworth is known for his calmness, openness, and capacity to listen. “I am caught off guard, always,” says his frequent collaborator, designer Lorenzo Savoini. “For Alan, listening is like an action, whereas for a lot of people listening is waiting your turn for what you want to say.”

Dilworth is currently in rehearsal for his first production as artistic director of Toronto’s Necessary Angel Theatre Company. The Events, by Scottish playwright David Grieg, was partly inspired by the 2011 mass shootings in Norway and involves two actors (Raven Dauda and Kevin Walker) and a different community choir every night. For The New York Times’ Ben Brantley, reviewing the 2015 New York Theatre Workshop production of The Events, that latter element evoked “Greek tragedy, in which choruses of common humanity echoed and annotated the words of afflicted heroes.”

Little surprise then, that this play spoke to Dilworth: not only does it reflect the internationalism that is a hallmark of his theatrical work (and which drew him to Necessary Angel), but it also demonstrates his ongoing engagement with classic tragedies.

“Richard Rose said to me once about my play, The Unforgetting,” recalls Dilworth. “He said, ‘you know, maybe you don’t know this, but I think you’re working on Greek tragedy all the time. That’s where you’re living’.” Dilworth tells me this during a lengthy conversation at the Little Portugal restaurant Wallflower, which he chose as our meeting spot because it’s one of his theatrical crucibles: he and his wife, the actor Maev Beaty, lived in the building in the early naughts and workshopped plays together in a ground-floor open space, which is now the restaurant itself. I don’t prescribe a particular focus for our conversation and it ranges wide, all the way back to Dilworth’s undergraduate years at UBC where he earned a BA in international relations and drove an orange camper van up to northern BC in the summertime to plant trees.

Dilworth tells me this during a lengthy conversation at the Little Portugal restaurant Wallflower, which he chose as our meeting spot because it’s one of his theatrical crucibles: he and his wife, the actor Maev Beaty, lived in the building in the early naughts and workshopped plays together in a ground-floor open space, which is now the restaurant itself. I don’t prescribe a particular focus for our conversation and it ranges wide, all the way back to Dilworth’s undergraduate years at UBC where he earned a BA in international relations and drove an orange camper van up to northern BC in the summertime to plant trees.

He differentiates himself from many of his collaborators in that theatre was not always part of his narrative, and at 49 he’s also a bit older than theatre artists with whom he’s closely associated, including Beaty, Savoini, Andrew Kushnir, and Erin Shields (“I’m six years older than you think I am,” says Dilworth).

During his UBC years, he spent a pivotal summer in Indonesia working for the World University Services of Canada: he did research into political theatre, and was inspired by a school principal he met in his Yogyakarta neighbourhood: “I really admired what he was doing in terms of his impact in his community.” Returning to Toronto (he’s originally from Mississauga), Dilworth earned a B.Ed. at York and became a full-time grade two teacher, commuting from a shared house in Cabbagetown to Bolton.

He says he loved that work, and at the same time his interest in theatre was growing through an engagement with the work of the Drama in Education pioneer Dorothy Heathcote and the OISE profs whose work had been deeply influenced by her: David Booth, Larry Swarz, and Debbie Nyman. “It really sparked something in me,” says Dilworth, “these collective engagements around an issue and creating story around it.” He sees a connection between this and his interest in the classics: “It’s almost like Greek tragedy in a way, like it was community coming together to try to tell these stories about an issue.”

He says he loved that work, and at the same time his interest in theatre was growing through an engagement with the work of the Drama in Education pioneer Dorothy Heathcote and the OISE profs whose work had been deeply influenced by her: David Booth, Larry Swarz, and Debbie Nyman. “It really sparked something in me,” says Dilworth, “these collective engagements around an issue and creating story around it.” He sees a connection between this and his interest in the classics: “It’s almost like Greek tragedy in a way, like it was community coming together to try to tell these stories about an issue.”

This many years later, he can track the influence of this engagement with Drama in Education on his approach to directing: “It’s providing contexts and processes to follow impulses, explore, and make space for [fellow artists’] curiosity to co-create. I feel that this has never left; it’s how I understand a rehearsal room at its best.” He is quick to note, though, that this “doesn’t mean that there’s not a vision at play… leadership is a many-faceted thing.”

Leadership: another big theme in Alan Dilworth’s career.

But before we get to that, we need to double back to 1999, when Dilworth followed his burgeoning interest in theatre into the first Soulpepper training company, where he reconnected with Beaty (they had first met on a U of T graduate student’s production of King Lear, which Dilworth says was “terrible… I can’t remember the director’s name and I wouldn’t even say it if I did.” Many people quit but he and Beaty didn’t: “We somehow looked at each other and said, ‘yeah, this is all brutal, but we can handle this’”).

Walking away from the offer of a permanent teaching job into the summer-long Soulpepper training was a big decision: “I felt like I was compelled to do it. I felt like maybe I was destroying my life,” says Dilworth. But at Soulpepper he started to absorb the concept of a career in theatre. “I witnessed some of those artists like Diego [Matamoros] and Oliver Dennis and Nancy [Palk], and I went ‘oh my gosh, there is life happening’… at least it’s possible.”

Walking away from the offer of a permanent teaching job into the summer-long Soulpepper training was a big decision: “I felt like I was compelled to do it. I felt like maybe I was destroying my life,” says Dilworth. But at Soulpepper he started to absorb the concept of a career in theatre. “I witnessed some of those artists like Diego [Matamoros] and Oliver Dennis and Nancy [Palk], and I went ‘oh my gosh, there is life happening’… at least it’s possible.”

Soon after finishing at Soulpepper, Dilworth and Beaty went to Calgary to work on a production, fell in love, and returned a couple. Then followed the Little Portugal years, during which they ran the indie company Belltower Theatre with Patrick Robinson while Dilworth side-hustled as a supply teacher and Beaty as a restaurant server. They started making shows for indie contexts including SummerWorks and felt like “we had all the time in the world on our hands,” says Dilworth. He and Beaty underline how formative those years were, and how lucky: “Right now, I know so many young people who I see working so many jobs,” says Dilworth. “I don’t know how they’re practicing what they do.”

“It was OK to do one waitressing job and still pay for our lives,” says Beaty, when I ask her to elaborate on her and Dilworth’s early careers in Toronto.

It was at this point that Dilworth started to write and direct plays – Ma Jolie, about Picasso, and The Unforgetting, which won the 2004 SummerWorks Jury Prize. “I met [Alan] as an actor,” says Beaty. “A very good and hilarious actor; he probably doesn’t want me to say that… I watched this writer come out of this actor, then I saw him become a director… It’s like a Russian doll, to watch someone unfold themselves.”

He returned to York to study for an MFA in directing (2007-09), an opportunity to turn his autodidactic approach into “something more formal,” he says. He read a lot of plays and encountered some new practices and practitioners – perhaps most importantly, the work of the iconoclastic English playwright Edward Bond. Reading Bond’s Lear, Dilworth says “I couldn’t believe that someone was saying the kinds of things that rang so true to me about the brutality of force, law and order, and justice and injustice. It was just so raw, and I felt less alone.” He built a strong working relationship with the writer (who is now 85), and in 2012 with Beaty organized an Edward Bond Festival in Toronto. He says that Bond’s work has deeply affected the way he works with playwrights. “He said to me, ‘you know, so often, I see plays of mine produced where a director thinks they’re fixing a problem. And the problem is that they’re actually not looking at the thing.’ If you enter it, a room opens up and the whole play changes, you know?” From Bond, Dilworth says he learned to respect the specific ways in which writers express themselves rather than expecting them to “fit a form.”

He says that Bond’s work has deeply affected the way he works with playwrights. “He said to me, ‘you know, so often, I see plays of mine produced where a director thinks they’re fixing a problem. And the problem is that they’re actually not looking at the thing.’ If you enter it, a room opens up and the whole play changes, you know?” From Bond, Dilworth says he learned to respect the specific ways in which writers express themselves rather than expecting them to “fit a form.”

So the York MFA was a success, then? “I got exactly what I wanted out of it, and I came out of there on fire.” Soon after came productions of Shields’s If We Were Birds (based on the Greek myth of Tereus, Philomela, and Procne), which went from SummerWorks to Tarragon to Shields earning the 2011 Governor General’s Award for drama; and the multiple-award-winning documentary collaboration with playwright Kushnir for Project: Humanity, The Middle Place. He and Beaty started the indie company Sheep No Wool and began to get gigs at major theatres including the Globe Theatre in Regina, Tarragon, Canadian Stage, and Soulpepper.

Dilworth’s first Soulpepper directing assignment was also his first time working with designer Savoini, on an adaptation of Schnitzler’s La Ronde by Jason Sherman in 2013. This was the beginning of what Savoini characterises as “an exciting working relationship… a shared aesthetic, an interest in what interesting theatre is.” As the daisy-chain scenes of La Ronde played out, Savoini’s set “devolved or came apart,” the designer says, “as scenes would start to expose the backstage theatre world.”

Early in our conversation I asked Dilworth if he feels called to leadership. He returns to this theme when he talks about his relationship with Soulpepper – first as co-associate artistic director from 2016, and then, suddenly in early 2018, as acting artistic director after founding artistic director Albert Schultz resigned following accusations of serial sexual misconduct and predation (legal actions against Schultz by four female actors were subsequently resolved out of court).

I suggest that accepting the invitation from the Soulpepper board to lead the company must have been intimidating. “Everything gave me pause,” he says, but yet he felt “compelled” to step in. “I felt that with my personality and background, I knew that I could hold some space… and I would work hard to make space for other people holding space too.” He ended up spending a year in the acting artistic director role, during which time the theatre (led also by interim executive directors Kevin Garland and Lisa Hamel) remained open; made its way through legal action (Soulpepper was named in the four actors’ suits as well as Schultz); delivered its scheduled programming (with a few cuts and amendments); curated, programmed, and began to deliver 17 subsequent months of work; and hired new executive and artistic directors. Soulpepper’s 2019 box office revenue was the theatre’s highest since 2016.

I suggest that accepting the invitation from the Soulpepper board to lead the company must have been intimidating. “Everything gave me pause,” he says, but yet he felt “compelled” to step in. “I felt that with my personality and background, I knew that I could hold some space… and I would work hard to make space for other people holding space too.” He ended up spending a year in the acting artistic director role, during which time the theatre (led also by interim executive directors Kevin Garland and Lisa Hamel) remained open; made its way through legal action (Soulpepper was named in the four actors’ suits as well as Schultz); delivered its scheduled programming (with a few cuts and amendments); curated, programmed, and began to deliver 17 subsequent months of work; and hired new executive and artistic directors. Soulpepper’s 2019 box office revenue was the theatre’s highest since 2016.

Dilworth says he’s still coming down from that experience, which he describes as “a time of intense stretching, at times tearing. I remember it as a time of intense change, intense rapid change… knowing from the beginning that it was going to be filled with compromises, absolutely rife.”

Beaty saw something emerge in Dilworth during that difficult time: “You can know someone for 20 years and be their biggest fan. It’s like you know every inch of an apartment building, and then you discover this penthouse suite… the elevator which goes up to Alan as leader.” Savoini credits Dilworth for helping rebuild Soulpepper’s work culture. “He just has a particular interest in taking care of the soulfulness in the room, the spirit in the room… he understood how important it was for a very damaged and hurt ecosystem to find a way to breathe and heal.”

Savoini credits Dilworth for helping rebuild Soulpepper’s work culture. “He just has a particular interest in taking care of the soulfulness in the room, the spirit in the room… he understood how important it was for a very damaged and hurt ecosystem to find a way to breathe and heal.”

Dilworth introduced at Soulpepper what he calls the “stillness room” – a 15-minute voluntary, shared practice where members of the company could come into a space to sit in silence, sometimes at the top of a rehearsal, sometimes at lunchtime. While this reflects his longtime interest in Zen Buddhism and his own commitment to a meditation practice, he says that the stillness room did not require any particular commitments: “There’s no Buddhism, there’s no prayer – or there can be. There can be any of that, whatever it is, but there’s just going to be silence and stillness for 15 minutes.” It’s a practice he extended into his work at the Stratford Festival (where he directed all three installments of Kate Hennig’s Queenmaker Trilogy) and is still using now, in rehearsals for The Events.

Recalling that year, both Dilworth and Savoini bring up their production of Idomeneus, Roland Schimmelpfennig’s contemporary retelling of the end of the Trojan War. The play—about a community devastated by loss, struggling to find a way to narrate its experience—oddly mirrored what was happening at Soulpepper at the time. Dilworth had brought the play to the company and his production was scheduled to open only two months after he’d taken over as acting artistic director. Directing it at that point was “madness because of my workload” but he nonetheless pushed forward rather than handing off the project to someone else: “it was very important to tell that story, for our time and also in the middle of the crisis. It was an investigation of power, told with such complexity.”

Recalling that year, both Dilworth and Savoini bring up their production of Idomeneus, Roland Schimmelpfennig’s contemporary retelling of the end of the Trojan War. The play—about a community devastated by loss, struggling to find a way to narrate its experience—oddly mirrored what was happening at Soulpepper at the time. Dilworth had brought the play to the company and his production was scheduled to open only two months after he’d taken over as acting artistic director. Directing it at that point was “madness because of my workload” but he nonetheless pushed forward rather than handing off the project to someone else: “it was very important to tell that story, for our time and also in the middle of the crisis. It was an investigation of power, told with such complexity.”

“It was surreal to be working on that play,” says Savoini. “Every day you’d hear words differently. It’d be amplified by the fact that those particular people were saying those particular words… there was a complex reverberation that would leave you a bit dumbfounded.” Schimmelpfennig’s embrace of ambiguity was part of what made the experience uncanny: “It’s a much more complex, grey narrative than maybe some would want to lead us to believe,” says Savoini. He and Dilworth had already planned an abstracted design, with the action played on black gravel against a stained concrete back wall, and the actors wearing contemporary grey clothing covered in white stains, and vertical bars of lighting hanging from the ceiling. The results (I can attest) were striking and unsettling.

“I think about them all the time,” Dilworth says of the people in and around Soulpepper he came in contact with during that year. “I dream about them all the time.”

Now he’s running Necessary Angel, a job he’s been eyeing for some time – he applied for the artistic director job in 2013 and lost out to Jennifer Tarver, which may not have been the worst thing. “I don’t think I would have been ready, given what’s required of the job,” he says. The company’s commitment to a combination of international and Canadian work and the fact that it’s “artist-led… striving to serve visions, artistic visions” of all sorts is what makes it so attractive to him, as does the fact – particularly at the moment – that leading it does not involve running a building. Even in the rush to get everything sorted out for his first season, Dilworth says it feels “breathable… I feel like I’m in the right place at the right time… I feel really lucky, and alive, and inspired.” The emotions Beaty expresses are “relief and excitement.” She says that “more space has opened up for curiosity” for Dilworth. “He can listen a little bit more clearly to himself and his impulses.”

Savioni too sees this as a new phase for Dilworth: “There is a place you get to when you develop a kind of distinctive confidence, or confidence with your instincts.”

Dauda, who first worked with Dilworth on Minotaur at Young People’s Theatre (Greek myth, again!), says that she’s never met anyone who’s so “worldly – he knows so much about so many things – and is still so much in a place of learning, of being open to what everyone brings to the table… he creates an environment where everyone is open.”

It makes “perfect sense” to Beaty that Dilworth is running this company at this point. “I have watched the moment meet the man time and time again.” And that takes work. “I have seen the daily efforts he puts into himself to remain open – open to love, curiosity, lessons. That takes more effort than a lot of us have the courage to do.”

Comments