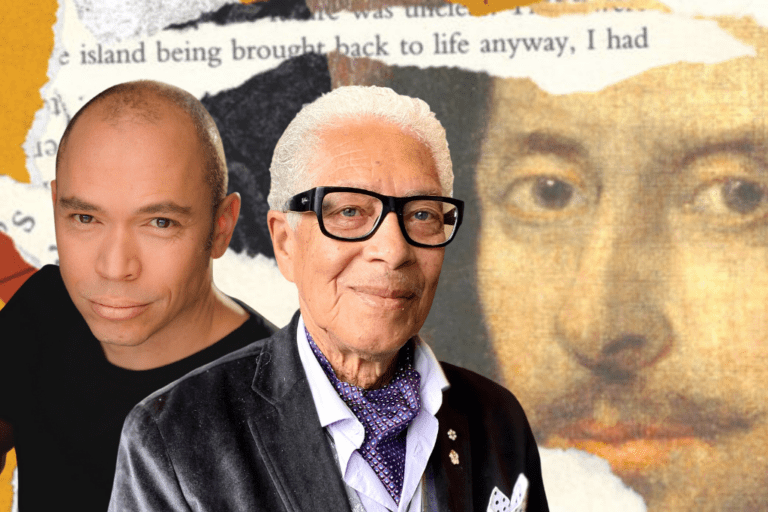

Spotlight: Soheil Parsa

In a life already full of fascinating chapters, Soheil Parsa has turned another page. Early this summer, Parsa stepped down as co-artistic director of Modern Times, the theatre company he co-founded three decades ago with Peter Farbridge. The “dream” now for Parsa, as he characterizes it, is to work as a freelance director, liberated from fundraising and administrative responsibilities.

Toronto’s Factory Theatre has already taken up the opportunity to employ this six-time Dora Award winner: he’ll be directing Wildfire by David Paquet (translated by Leanna Brodie) as the final show in Factory’s 2021-22 season. It will likely come as a surprise to many who admire his work that this will be Parsa’s first time directing a fully staged production in Toronto for a company other than Modern Times. Earlier this year, he directed The Parliament of the Birds for Soulpepper Theatre, as part of its Around the World in 80 Plays audio series. 2021 has also afforded Parsa two major recognitions: the Barbara Hamilton Memorial Award from TAPA, and an honourary membership from CATR/SQET.

“It is great news that Soheil is available to be hired,” said theatre scholar and dramaturg Ric Knowles, who has collaborated on a number of productions with Parsa, in an interview. “I imagine people all over the country scrambling to hire him, because he is one of the country’s best directors.”

He doesn’t think that he knows. He doesn’t go in with that attitude that he’s God and he knows.

This transition seemed a welcome moment to celebrate Parsa’s contribution to Toronto and Canadian theatre, and to ask him to talk about where he’s heading. That contribution includes both a distinctive approach to stage directing, and the mentorship and leadership he has provided for other immigrant and non-white theatre artists on the Toronto scene (he himself is originally from Iran). Running through Parsa’s work is a deep commitment to collaboration, a resistance to being pigeonholed as a culturally specific artist, and a lifelong passion for creative exploration: “I’ve never stopped investigating,” said Parsa in a two-hour-long interview in May.

“As much as I love many directors that I have worked with, Soheil is unique,” said his frequent collaborator and friend Beatriz Pizano in an interview. “He’s a beautiful human being on top of that. So respectful, so caring, and so humble… he’s doesn’t think that he knows. He doesn’t go in with that attitude that he’s God and he knows.”

When Pizano moved to Toronto from Vancouver in the early 1990s, she had difficulty getting stage work because she speaks English with a Colombian accent. Parsa was the first theatre director to cast her, helping propel her into an award-winning career as performer, playwright, director, and artistic director of Aluna Theatre. “He casts the person regardless of diversity… he chooses the person that is right for the role,” said Pizano. The two are currently working together again: Parsa is directing Pizano in the title role of Federico Garcia Lorca’s The House of Bernarda Alba, a co-production between Aluna and Modern Times scheduled for a March-April 2022 run (it’s the first time Parsa is working as a freelance director for Modern Times).

When Parsa and I met, our conversation quickly turned to his early interest in theatre, fed by a visit to the Shiraz Art Festival in 1970 with his older brother, where he saw Peter Brook’s Orghast and Argentina-born director Victor Garcia’s production of Jean Genet’s The Maids. The work in Shiraz “was absolutely the highest standard,” said Parsa. “The avant-garde movement of the West was very important.”

His undergraduate theatre education at Tehran University was also very international. He and his classmates became familiar with plays by Samuel Beckett, Arthur Miller, and Lorca along with traditional and modern Persian forms and artists. “We have a great tradition of translation in Iran,” said Parsa. A key figure for him during those years was playwright, theatre director, filmmaker, and educator Bahram Beyza’ie, who sparked in Parsa a particular interest in Japanese and Chinese theatre traditions. Parsa has gone on to direct a number of Beyza’ie’s works in English translation for Modern Times, including Aurash, The Death of the King, The Eighth Journey of Sinbad, and The Four Cases.

The Iranian Revolution of the late 1970s changed everything, and had particular implications for Parsa and his family, who are of the Bahá’í faith. While Parsa himself was and is not actively engaged in this tradition, he was not a supporter of the Revolution. Things became “complicated” for him in university when the powers that be became aware of his faith background. “They said to me, if I wanted to continue my work as a theatre artist, I would need to convert to Islam… my parents started to get into trouble. They were arrested for a short period. And I realized that I couldn’t stay in that country anymore.”

Parsa and his wife – then a medical student, and pregnant – were expelled from Tehran University. Parsa sold their possessions, paid a smuggler to get him across the border to Pakistan, and met up with his wife in Dubai; they ended up in India as refugees of the United Nations, with their son as a babe in arms. They were given three choices of countries in which to settle; not being fans of U.S. foreign policy and finding Australia too far away, they decided on Canada, and arrived here as landed immigrants (who are now called permanent residents) in 1984.

Having arrived with very little English and with hopes of pursuing a theatre career in Canada, Parsa enrolled in the theatre program at York University to better learn the language. He understands himself to be one of the first people from the Middle East to enroll in theatre school in Canada.

Parsa spoke with admiration and affection about a number of his York professors, in particular the late Anatol Schlosser: “God bless him, he was amazing… He was teaching a non-European theatre course and he encouraged me to take it.” Schlosser urged Parsa to bring his knowledge of Persian theatre into the course. “He was very curious about my work.”

I thought, I have to create opportunities for myself.

With some other of the York faculty, there were problems: “I don’t want to say it was prejudice, that they were against me. I think they just didn’t want to deal with me. They were very naïve as well.” He ruffled some feathers when, in his second year, he staged an extracurricular production of Brecht’s A Man’s A Man – his first foray into directing. While he was happy with the production as a creative exploration, and through it made his first connection with Farbridge, who acted in the show, Parsa acknowledges that “it was not a good decision to do it, because I sucked the energy of the department and that is not right… the teachers got pretty upset.”

A specific critique of Parsa’s production offered by a faculty member had to do with the acting style. “The professor said he enjoyed the show, but he said that here at York, we’re teaching realism and naturalism to prepare students for Shaw and Stratford.” Parsa found this hard to square with the fact that York (as had Tehran University) taught Brook’s The Empty Space and Jerzy Grotowski’s Towards a Poor Theatre as core texts, which are hardly manifesti for naturalist and realist theatre. “I found a lot of contradictions there,” said Parsa.

On his graduation day, a professor called Parsa into his office. “He said, I’ve been following your work,” Parsa recalled. “He said, ‘you’re a very interesting person, I think you’re very knowledgeable. But I’m sorry, Soheil, there is not going to be a future for you in this country. I hope the Iranian regime changes one day, and you can go back and become head of the National Theatre of Iran’.”

Parsa was bemused but undaunted, because the Brecht production had made him realize that he loved directing, and Canada was now his home. “That’s how the idea of founding Modern Times happened. It was exactly because I knew there would be no possibilities for me, nobody would hire me… in 1989 when I graduated from York, I was one of a handful of racialized artists in Toronto… I thought, I have to create opportunities for myself.”

And so he did. In the years that followed, Parsa and Farbridge built up the company, and Parsa developed his approach to stage direction. Those familiar with his work know that he has a distinctive and compelling aesthetic which does not fit into the realist/naturalist paradigm that continues to dominate English-Canadian theatre: relatively bare stages with a few key pieces of scenography; a deep integration of sound, lighting, and movement into the mise-en-scène; and an approach to performance in which actors use their whole bodies as well as voices to communicate meaning, and through which there is a clear sense of collective purpose and understanding.

While he wouldn’t necessarily describe himself as a minimalist, Parsa feels that an emphasis on elaborate sets and costumes, such as he observed back in Iran and in the work of some major Canadian companies, gets in the way for him: “Where is the story? I would love to see the actors, the human beings.” He accepts that for some actors this can be challenging. “Many actors say to me ‘Soheil, your production is scary… when I work with you, there is no place to hide’…. I know actors love props and want to have something to play with. But… you don’t need to play with your handkerchief or with your pen in your hand; this is distracting.”

Pizano initially struggled when working with Parsa on their first production together, The Daughters of Scheherazade – not necessarily with exposure, but with not knowing initially how all of the elements of the production would come together.

“We had a year of workshops. I remember walking into the first workshop, and there was a sound designer, Richard Feren; Stephen Droege was the set and lights… these people were working with you in that room. There was a choreographer, Norma Araiza was with us, so we were being trained physically… it was starting to understand [Parsa’s] vocabulary in terms of the lights and sound. All these design elements are also characters on stage with you. It was magical. I was coming from a very method acting school at the time, and he was coming from the physical – which really is what Stanislavsky was saying his later years. We have these memories that we laugh about, the day I broke down, finally, maybe in the second month…. I started to understand what it was to find that emotional work also coming from the physical, that it was not all this mental work to approaching a character that I have always had.”

This practice of developing a piece over an extended period of time with all creatives present is central to Parsa’s way of working (though increasingly difficult to fund and support within the Canadian granting system). When I asked him about this approach to creative development, he brought up his production of Macbeth, which he developed over the span of a year, and focuses on the place of semiotics in his work – the way in which he imbues meaning in bodies and objects on stage.

Semiotics for me is about creating meanings, more meanings than you can do verbally.

“The whole idea was to put a Western piece like Macbeth stylistically in context of ta’ziyeh and see what happens,” said Parsa, referring to the outdoor passion plays that are a traditional form of performance in Iran. “It wasn’t like changing anything, changing the story. It was Shakespeare’s story there. But the way we told the story… the semiotics, I really explore that.” There were no swords nor blood in the production: “All the actors were identified by a scarf in a specific colour. Like, Macbeth was purple, and Banquo was green.” A character killed another character by snatching their scarf from them. The scene of the murder of Macduff’s family became a massacre in Parsa’s production, with some 80-100 scarves representing the dead. “Semiotics for me is about creating meanings, more meanings than you can do verbally; in a lot of realism and naturalism you rely on words… semiotics is where the non-verbal aspect of theatre comes in.”

When it came to his award-winning production of Lorca’s Blood Wedding, the central physical element was panes of glass. “Somebody asked me why, I have no idea. I can’t say why, it’s an intuition, an instinct.” He gave the idea to scenic designer Trevor Schwellnus: “I said, this is what I see, Trevor. I see glass, [panes of] glass from floor to ceiling.’… he said ‘Soheil, you’re not going to change your mind,’ because he loved it.”

“Later on, when I started intellectualizing,” Parsa continued, “I realized that in this world, there’s no privacy – in Spain, in those villages, people are seen all the time. Gradually, things start to make sense… you trust your intuition.” Parsa does extensive research leading up to the start of a creative process, “but I don’t take that analysis into the rehearsal hall. I’m with the actors on my feet. I don’t have a chair or a table. I’m walking, I have to be close to the actors, to talk to them.”

Knowles discovered for himself just how collaborative Parsa’s process is when he sat in on rehearsals of Modern Times’ 2009 production of Hallaj, initially as an observer. “I was hoping to write about him and asked if I could come in. I ended up getting a credit as a dramaturgical consultant because he wouldn’t let me shut up.”

Parsa’s openness to others’ input, combined with his interest in artists from across backgrounds and traditions, combine to make his work “genuinely intercultural,” said Knowles in an interview: “He’s got Asian Canadians. He’s got folks like Bea, Latinx Canadians. He’s got people from the Middle East, he’s got Black folks, he’s got settler Canadians, he’s got Indigenous folks. So every room brings different theatrical traditions with it, different epistemologies, all mixing and blending in the room, and he listens to everybody, and watches and pays attention, and then makes decisions that are informed by that.”

Parsa has long served as a support and sounding board for other immigrant and racialized artists who are starting out in Toronto and Canadian theatre, and he knows that his story has become an important part of the immigrant artist narrative: “Majdi [bou-Matar] was saying that when he came to this country… everybody said, ‘Well if Soheil managed to do it, than you can do it,’” referring to the Lebanase-Canadian theatre director and founder of MT Space in Waterloo.

What you say is important. But what is more important to me is how you say it. That’s why we do theatre.

He’s excited by how much Canadian theatre has evolved over the years, and about the number of racialized and minoritized artists who are now in leadership positions. He has some concerns, though: “I’m hesitant to say this, but my fear is that we go the other extreme…. when things get easy, I don’t like it…. when I was on juries at the Canada Council, I would always say, ‘please, please don’t support me just because I’m an immigrant. Support me if you think I’m an artist, if you think I have merit’…. I’m not very popular among some brown people when I say that one.”

In our conversation, Parsa also expressed some concern about a tendency towards projects driven by socio-political issues alone. “I see a lot of this right now …. you want to talk about colonialism? Absolutely, but in what way to you want to talk about it? Are you just talking about content? Why have you chosen theatre?” He sees this among racialized and non-racialized artists alike. “When people approach me as a mentor, I say, can we talk about content as the last thing? You want to talk about anything, OK. The only thing I can help you with as a theatre artist looking for advice is the theatrical language. What is your theatrical vocabulary?”

“What you say is important. But what is more important to me is how you say it. That’s why we do theatre.”

Comments