To Train, or Not to Train: Exploring Stratford’s Birmingham Conservatory

It’s hard to find anyone living in Canada who hasn’t at least heard of the Stratford Festival. As the largest classical repertory theatre in North America, the internationally recognized festival offers more than a dozen shows every year across four venues. But incredible staged Shakespeare productions aren’t the only artistic opportunities the festival offers.

For more than twenty years, artists across the country have looked to the Birmingham Conservatory, Stratford’s artist incubator, for opportunities to develop their craft and refine their classical technique. But despite more than two decades spent training early and mid-career artists, the conservatory remains under the radar of many theatre-makers and audience-members.

Chanakya Mukherjee considers himself lucky in this regard: it was his teachers at the University of Calgary who directed him towards the conservatory. Having moved to Alberta from India after high school, he quickly learned that many Canadian theatre actors consider the Stratford Festival to be the pinnacle of classical performance opportunities.

“My teachers saw my ambition [in classical theatre],” he said in an interview. “We didn’t really discuss the conservatory in classes, per se, but in individual interviews, my professors kept saying, ‘hey, maybe this is something you want to look into.”

But knowing about the program isn’t the same as understanding exactly what it offers. Mukherjee moved to Toronto in 2016 and spent a year working in theatre across the city before auditioning for the Birmingham Conservatory in 2017. At the time, he had a very specific, though admittedly inaccurate, idea of what the conservatory offered.

“I saw [the conservatory] as a way for me to get my foot into the big machine that is Stratford,” he said. “And I guess, in some ways, that was a misunderstanding on my part — it’s not that the Birmingham Conservatory is training you to be a Stratford actor. Sure, there are benefits of being accepted that are specific to Stratford: I’m more aware of the work culture here, the specific demands of the different spaces. The Tom Patterson Theatre, as it is right now, is one of the most unique theatres that I’ve worked in. Both it and the Festival Theatre require specific activation of your instrument, which you can work on through the program. But what I’m learning right now is giving me the confidence to take this newly gained knowledge anywhere in the world and flourish.”

Although he didn’t make it into the conservatory after his first audition, Mukherjee is currently one of the nine members of the 2022/23 cohort. Now halfway through the program, he’s already made his Stratford debut in the 2022 productions of Richard III and All’s Well that Ends Well, two of the classical offerings from the past season. And as he admits, the timing was perfect.

“I got this opportunity exactly when I should have,” he confessed. “If I was here in 2017, I wouldn’t have had the breadth of experience I had when I got here. It’s important not to rush into the program. As with any professional development, you want to have some professional context outside of the program itself. You need to have some sort of understanding of what are your interests as an artist: even an inkling is perfect. If you have curiosities, you have questions, you’re starting to think, ‘okay, I think this is what I like.’ As life progresses, perhaps your opinions will change. So, gain experience, see what you might want to research that [Stratford] can provide.”

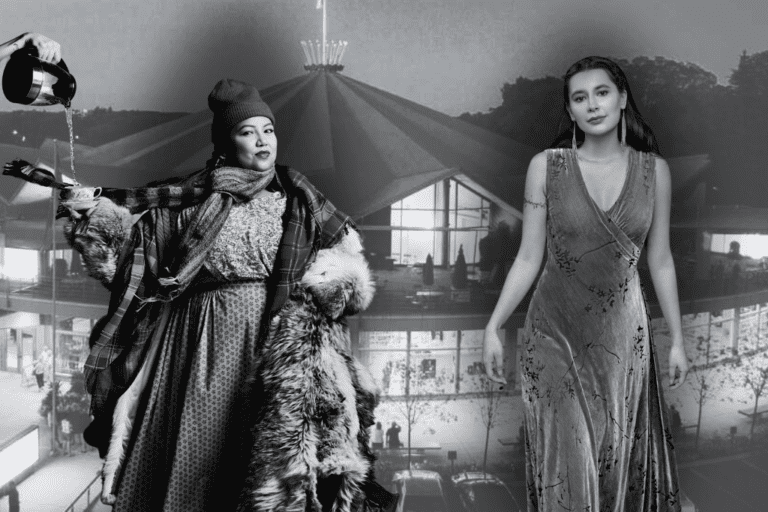

Andrea Rankin, a 2019 participant in the conservatory, agreed. She recently completed her fourth season with the Stratford Festival, where she played Ophelia in their acclaimed production of Hamlet.

“In this industry, we always think we’re running out of time: you do have time. You don’t have to rush into the training if you haven’t rediscovered that curiosity.”

And for Rankin, it was the festival itself that piqued her curiosity in the Birmingham Conservatory. She was born and raised in Edmonton to Toronto-born parents, so although she spent her childhood in Alberta, she was always well aware of the Stratford Festival. After completing her BFA in acting at the University of Alberta, Rankin moved to Toronto with her eye on the Stratford stage, among many others. Her festival debut came in 2018, when she played Anne Brontë in the world-premiere of Jordi Mand’s Brontë, as well as roles in The Comedy of Errors and Paradise Lost. Staff at the festival encouraged her to audition for the program, and, describing herself as a lifelong student, she decided to go for it.

“The late, great Ian Watson once told me, ‘sometimes it’s worth having an experience so you can explore different perspectives and figure out which ones are most useful to you,’” she recounted. “And I think that’s so important, as an artist. You need to have your own perspective, but you also need to want to explore the perspectives of others. Trust that the people who work there have an array of diverse perspectives for a reason; meet that with an openness and curiosity for other people and their experiences.”

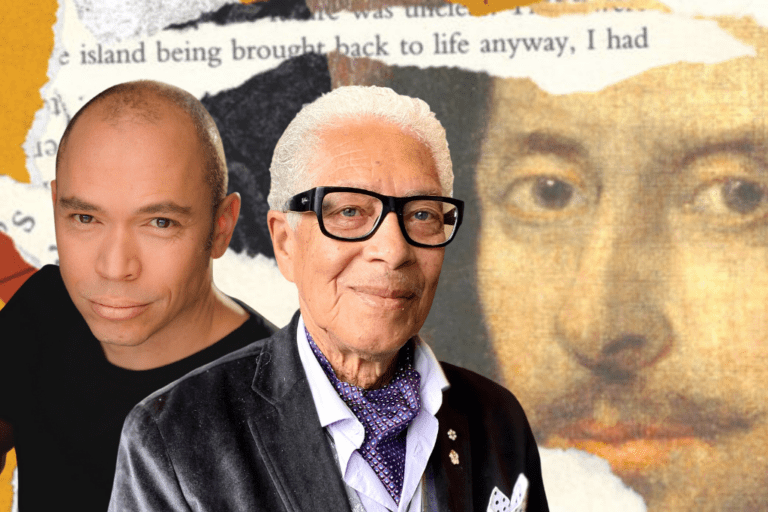

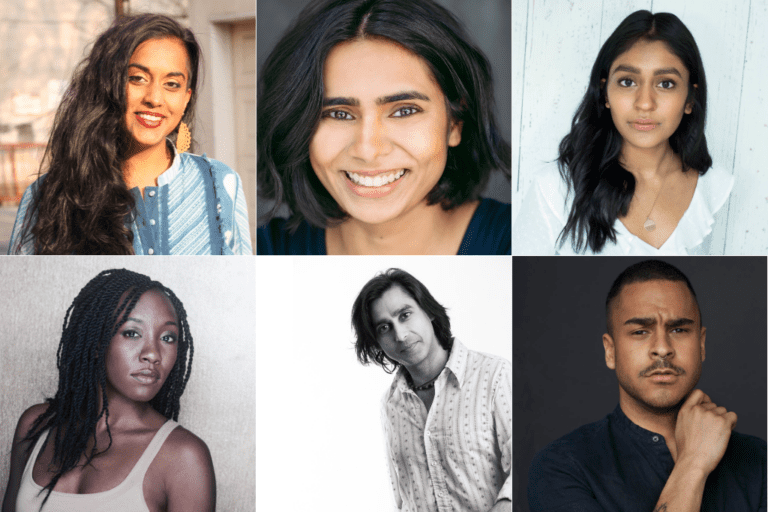

It was the Stratford Festival’s artistic director at the time, Richard Monette, and master teacher Michael Mawson, who founded the program as a conservatory for classical training in 1999. While the Birmingham Conservatory has changed significantly over the past twenty years, the base goal of the program remains the same: to provide Canadian artists with top-tier training. Nowadays, the program accepts up to eight actors and two directors, coaches, designers, or multidisciplinary artists into each cohort. Intended for artists with two to five years of professional experience, the conservatory is aptly named. The Festival views the program as an opportunity for actors to nurture and grow their toolbelt, and for those in the non-acting stream to deepen their understanding of voice, movement, and text work while receiving mentorship from a professional in their field. Rather than providing foundational training, their focus is on providing working, professional artists with the space and resources they need to develop their craft.

André Sills, a lauded Toronto-based actor and director, was part of the Birmingham Conservatory in 2005, when it was still helmed by one of its first directors, David Latham. He initially auditioned for what was then a one-year opportunity in 2004, straight out of his acting program at George Brown College. Ultimately, he spent that year performing in various sizes and scales of Shakespeare’s works on Toronto stages.

“There was Othello at Hart House, and Macbeth at Theatre by the Bay,” he recalled. “Oh, and of course Much Ado About Nothing in Hyde Park. It was a busy year, I’m very lucky.”

Despite having a lengthy resume of classical roles at a fairly young age, Sills wasn’t interested in the program simply for the Elizabethan opportunities.

“I wouldn’t say I entered the conservatory program because I wanted to work exclusively on classical texts for the rest of my career.” He laughed as he recounted, “I was always young and ambitious — I had very specific goals. By that time, I’d already played Othello, I’d played Macduff. I remember thinking that there were so many possibilities [at Stratford]. And I knew about the size and scale of the stages. The stage that I grew up on was at the church I went to as a child: it was a big church, probably about 2200 people. So crowds didn’t scare me: I kind of loved it. Seeing what the Festival Stage was like didn’t intimidate me, but the formation of it — that thrust — was new and exciting.”

Opportunities or not, the decision to audition for the program was not one Sills took lightly. Like Mukherjee, he believed that the Birmingham Conservatory would mean taking time off from his budding professional career.

“Coming into the program right out of school, within two years, I was worried that it was going to feel very much like I was being graded,” Sills said. “But it wasn’t. Yeah, at the time we were taking six months away from the city, from the hustle and grind of Toronto, but it was a different hustle and grind in Stratford. Not necessarily the hustle and grind of having to work your restaurant job then trying to find a way to film three self-tapes in the morning. Instead, you were training and performing with resources that might not typically be available to you, both financially and in terms of mentorship.

“That’s the exciting part, that at no point have I stopped being a professional,” Mukherjee agreed. “I’m still very much embedded in [the industry and the work]. I think that might have made me nervous, if my understanding of the program was that you have to exit and re-enter the profession.”

Although it would be easy to describe the program simply as a “paid training opportunity,” the benefits of for its participants go far beyond the financials. For Muhkerjee, the most valuable resource participants are provided are the mentors and leaders with whom they can collaborate.

“One of the most exciting parts about this particular iteration [of the program] is the circle of leadership and mentorships,” he noted. “There is a core circle, and then there are external artists, some of whom are performing in the festival, some of whom are not a part of the festival right now. Someone who has been instrumental for me in this process so far is [Conservatory associate artist] Raoul Bhaneja, and his insight into the work as a brown Canadian artist…These are the sort of mentors that have been provided to us, and they’ve been responsive to us. As we’re growing and researching, we can check in with people about where we are with our process and where we can continue to move forward.”

Today, the Birmingham Conservatory is a two-year program overseen by Janine Pearson, who has been the program’s director since 2021. She is the latest in an illustrious legacy of conservatory leaders, following Mawson (1999–2000), Latham (2001–2006), Martha Henry (2007–2016), and Stephen Ouimette (2016–2020). With each new program director, the program evolves, and each iteration becomes a reflection of its leader.

“Janine has been a [voice and text coach] here for a long time,” Mukherjee told me. “Her understanding of the craft, her experience of it has been centred around the voice, the breath, and the word, and how you cut through those elements to get the stories to people. Classical works present a good vehicle to try those things out… It’s sort of challenging yourself at a higher level to discover what your instrument is capable of.”

You do have time. You don’t have to rush into the training if you haven’t rediscovered that curiosity.

For each of these three actors, the Birmingham Conservatory has offered them a multitude of benefits, both in their personal and professional lives. As he heads into the 2023 season, Mukherjee has reflected on how the program offered him a surprising opportunity to reconnect with his heritage through an interdisciplinary solo exploration project from the first three weeks of his program called the Arrivals Legacy Project. He recommends that future applicants view the conservatory as an opportunity to tell their stories and find amplify their voices in a supported, open environment.

“If you see that you can bring some change into the organization, please apply. Maybe your vision for yourself is bringing the kinds of work that you don’t see on the stage here: know that it’s better to be here and making those connections, making way for these works than to be on the outside, you know, shaking your fists. That’s how we propel change. That’s what keeps it exciting for us artists.”

He reiterated that artists need not worry about taking time off from their careers to pursue the development opportunity.

“I can commiserate with any hesitancy to go back into any kind of training, especially after you spent four, three, or two years training. And now, you’re tacking on more? But in my mind, Birmingham is a unique opportunity because it is training within the context of being able to do the work.”

Rankin found that alongside the training and mentorships, the relationships and connections she formed in the conservatory and while living in Stratford have been life-chaning.

“I sometimes find it hard to separate my experiences in the conservatory from the four years I worked and lived in Stratford,” she admitted. “But those bonds I formed, and the relationships I fostered — especially with the women in the program — are something I’ll never forget. Having that support system was incredible.”

Rankin’s advice for prospective Birmingham participants is simple: don’t rush.

“If you’re looking to do the program, ask yourself why. It’s important that you have the chance to decide for yourself when the right is time. You might want to develop your own perspective and artistic voice, so if you need time to nurture that, take that time.”

After reflecting on the many artists he had the opportunity to work with through the program, Sills was all smiles. Pearson, Latham, Nancy Benjamin, Jane Gooderham, Suzanne Turnbull and the late Bernard Hopkins, among many others — he had fond stories and memories of each. But looking back at his time in the Birmingham Conservatory, he’s able to sum his experience up quite neatly.

“The program gave me the right seeds that I needed to water my artistry at the time.”

Comments