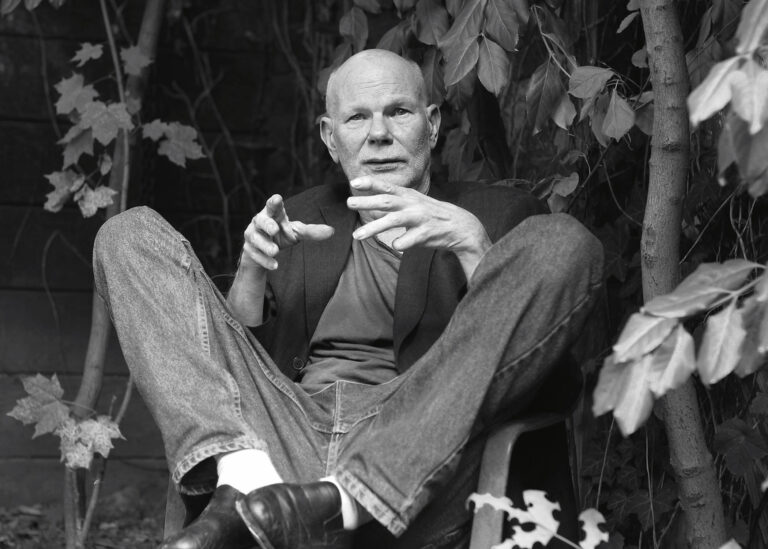

A Glimpse Behind the Moon with Anosh Irani

Anosh Irani likes to write about restaurants. His debut novel The Cripple and His Talismans had a call back to The Lucky Moon, a neighbourhood eatery where he hung out as a teenager. His 2018 play The Men in White, which premiered at Factory Theatre, is partially set in a Vancouver Indian joint. And his latest work, Behind The Moon — which just premiered at Toronto’s Tarragon Theatre — unfolds in a Toronto Mughlai eatery.

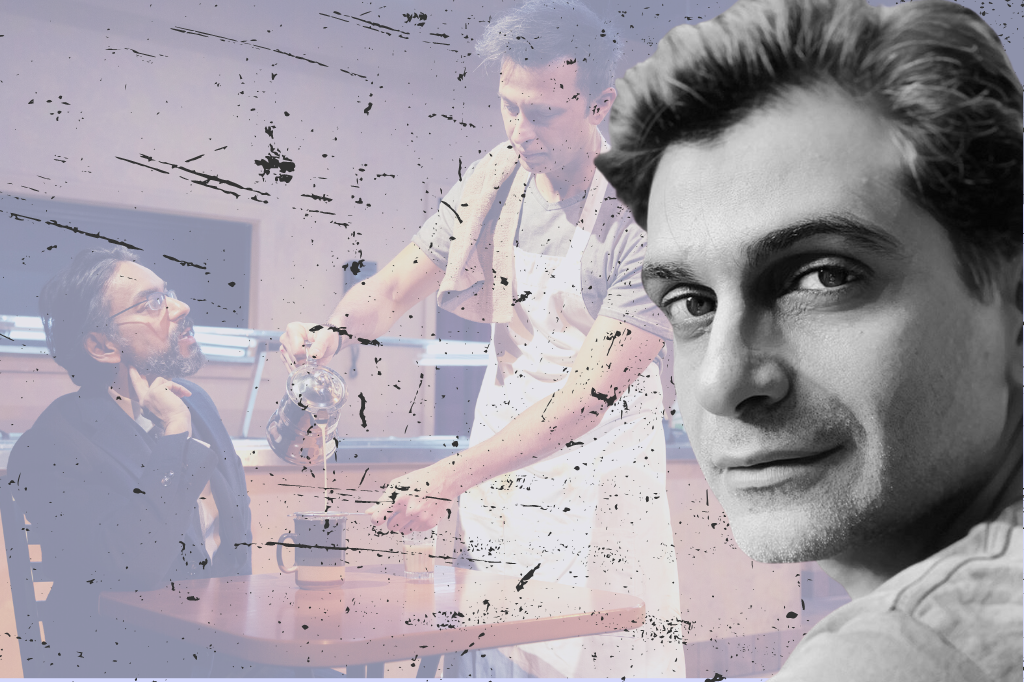

The Vancouver-based artist’s new piece follows Ayub (Ali Kazmi), an illegal immigrant from India working as a cook under the watchful eye of his boss Qadir Bhai (Vik Sahay). One night after closing, a cabbie named Jalal (Husein Madhavji) arrives, pleading for food. What unfolds is a story of faith, loss, and brotherhood, told through the lens of three very different Indo-Canadian life experiences.

I caught up with the celebrated scribe to chat about literary formats, strange characters, and achieving immortality through writing.

Chris Dupuis: What was your starting point for Behind The Moon?

Anosh Irani: My plays have strange trajectories in terms of how they evolve. My 2019 play, Buffoon, began as a commission in 2005. I’d wanted to write a circus play; it was originally called Manja’s Circus and had a cast of seven. It turned out fine and I was even offered a production by a theatre company, but something told me to wait. It was the clown in the play. He demanded his own show. He walked out of the play. That’s how I realized it was a solo. Fifteen years later, it ended up on stage as a one-person show.

With Behind the Moon, one of the characters from The Men in White kept haunting me. Ayub is a version of that character and I was extremely interested in his inner life: Why did he come to Canada? Who did he leave behind? Does he sleep well at night? What does he dream of? I wrote a short story about him (also called Behind the Moon), which was published in the Los Angeles Review of Books. The deeper I dug, the more [Ayub] revealed himself. Until, eventually, he showed up on stage, cleaning the glass counter of the restaurant he works in. If characters refuse to leave me, I just follow them. And listen.

You’ve written plays, novels, and short stories. Do you know the final form something will take when you start? Or is it something you figure out through the process?

Some stories arrive in a particular form and they’re never anything else. Buffoon started out as a circus play and became a one-man show. But it was always for the stage. On the other hand, The Matka King (Irani’s first play, written in 2003) began as a short story called “Bullet No.1.” But after the story ended, the main character continued to speak, and he was doing so in front of an audience. I realized he was dictating a monologue for the stage.

Most of your works have been set in Mumbai, your hometown, or Vancouver, where you currently live. This is the first thing you’ve written that unfolds in Toronto. Why did you want to write about a place where you’ve never lived?

The first reason was the weather. Ayub’s isolation gets more intense due to the extreme cold. He doesn’t understand it. It paralyzes him emotionally. I wanted this man who comes from Bombay, where it’s sunny all the time, to experience cold, dark winters, emotional winters, just physical ones.

The second reason is there was this Indian restaurant in Toronto where I used to eat. It’s exactly the kind of place where Ayub works. I would sit and make notes, and I just envisioned him there, lost, staring into the distance.

What’s the difference between writing a character for the page versus the stage?

It’s actually not that different. I always try to understand the inner lives of the characters before I worry about plot. Novels have tremendous interiority; they’re a means of reflection and meditation. Plays, on the other hand, demand that one moves in a trajectory. There’s a sense of doom that the characters are moving towards. At least, that’s the way it feels when I write.

In an interview you did a few years ago, you mentioned that you’re excited by the strangeness of certain characters, meaning you don’t understand their motivations. Are the characters in Behind the Moon strange?

Yes, absolutely. If I understand them perfectly, there’s no discovery. No investigation. I need to dig and dig, until I uncover something, some meaning behind their actions and words. With Behind The Moon, they’re strange in that they’re wounded in different ways.

Anosh translates as “Immortal.” Is there a connection for you between writing and immortality?

I have no interest in immortality. I really don’t care if my work gets read after I’m dead. What matters to me is the moment. In this moment, can I find some truth? Can I move the audience? Can I dent their consciousness in some way? If my work stands the test of time, so be it. If not, I won’t be here anyway.

Anosh Irani’s Behind the Moon, directed by Richard Rose, runs at Tarragon Theatre February 21 – March 19, 2023.

Comments