All the Little Worlds: Reflections on Directing with Martha Henry, Diana Leblanc, and Marti Maraden – Part 2

“So, you’re going to submit this article to Philip [Riccio, publisher and co-founder of Intermission Magazine]?” Diana Leblanc asks. There had been a wine and cheese break in my conversation with Diana, Marti Maraden, and Martha Henry, and Diana brought us back on track.

“Yes,” I say. “Eventually. When it’s something.”

I tell them that a couple of years earlier Intermission had asked me to write a piece about actor Tom Rooney. At the time, he was in rehearsals for Tartuffe at the Stratford Festival, and I imagined that his process and experiences working on that play would be at the centre of my conversation with him. I thought I was going to write about Tartuffe. And then, when we met, all we talked about was Hamlet, and so the piece became about Hamlet. “I loved that I had an assumption about what I was going to write about,” I tell them. “That I had this whole plan, and then immediately had to let go of it because it wasn’t what he was interested in talking about, or what we had in common to talk about.”

Meeting with Diana, Martha, and Marti, I had no plan. Or so I thought. I realised right out of the gate speaking with each of them that I had, in fact, already begun writing a story in my head. When I mentioned to Marti in an earlier conversation that I think of the three of them as the “first generation” of female directors in Canada, she quickly pointed me to several women who had come first. When I asked Martha if she felt it was harder for female directors to say “I don’t know” in a rehearsal room, she said, “I say that all the time.” I loved that once again I’d had a plan that was immediately thrown out the window.

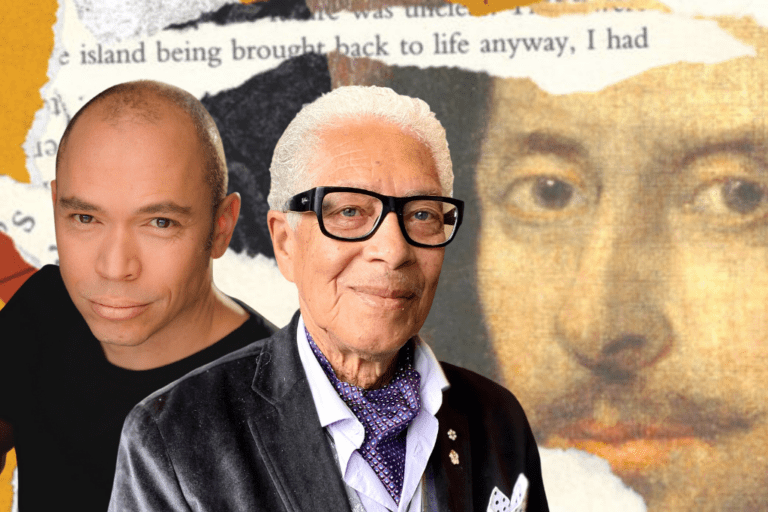

Marti Maraden. Photo by Mike McPhaden.

“And that’s an interesting topic for this,” Martha says and begins telling us about her first experience as a director.

MARTHA HENRY: When I was teaching—it’s interesting how many of us started being put in positions of being teachers when we weren’t teachers, and we knew we weren’t—the first time I was asked to teach was at the National Theatre School. The idea was to do one classical scene and one modern scene with the same actors so they would begin to understand that when they were doing a classical piece, they didn’t fall into “classical mode.” That the process still was the same, to find characters. The curriculum was all laid out. It involved reading about fifteen plays, and working with this class of the National Theatre School, which was Kate Trotter and… it wasn’t Seana yet, but it was—

DIANA LEBLANC: No it was—

MH: —It was the year before Seana. And we read… I had to do all this prep and read all of these plays and I knew I was going to have to block them. And usually you don’t have to do that unless you’re a director and I wasn’t a director, so I worked everything out on paper and I knew who was going to move where and when and on what line.

[laughter]

MH: And we started, and we read all the plays. I was shaking so much that I had a cup of coffee in my hand—we had those desks that had that side panel—and I would start to lift up my coffee cup, and my hand was shaking so much I knew I couldn’t get it to my lips. So I would immediately pretend to be just wildly interested in something—

[laughter]

MH: —that had just occurred on the page—

DL: —So you could put your cup down!

MH: —and I could put my cup down. And I did this throughout the whole of whatever it was—I guess it was a week—when we were reading these plays. And finally we got to actually staging the scenes and I got out my pieces of paper with everything I had written down and I would say, “You come in from there and you come in from there and you come in from there,” and they would all do that. And then I would open my mouth to say, “And then you go there,” but by the time I looked up, they’d already gone somewhere.

CHRISTINE HORNE: Right.

MH: And I would look and think, “Oh, yes, well, that’s better!” And then we’d get to the next place and I’d start to say, “And then you two go there and there,” and I would look up and somebody would usually have done something already so then I had to say, “Oh, okay, well then why don’t you go around there and come there,” and by the time we finished blocking it, the blocking was… I guess somewhere in the territory that I had originally devised, but basically it was different. It was theirs. So then I would say, “Okay, well, go through that again.” And I would look at it and go, “That’s much better than what I had imagined.”

[laughter]

MH: And so as we then went through the scenes I began to see it was good that I had done the homework, that was essential, but that having done it I could feel confident in the fact that they might have other ideas–

MARTI MARADEN: Exactly.

MH: —and be able to go in different directions. And by the time we finished that whole process I had just loved it. And I realised that I could block a scene. I’d been on stage all my life, I knew the difference between stage right and stage left—

[laughter]

MH: —I knew how to block a scene. And I didn’t even know that I knew that. And so, that to me was a huge revelation.

Like Martha, Diana got her start in directing by being asked to work with students at NTS. She chose to work on scenes from Canadian plays and loved it. The school then invited her to direct a production of Waiting for the Parade, her student actors including Susan Coyne and Paula Wing. She assisted Martha at The Grand, and Robin Phillips “tolerated her presence” at Stratford during the first year of the Young Company. She began directing in earnest in her fifties, working at The Grand, Théâtre français de Toronto, Tarragon, Centaur, and Stratford, among others. Prior to our conversation, when I asked if she thought she was the first female director some actors or designers had ever worked with, she said she’d never considered it. But when she looked back, she can see how some actors, both male and female, bumped up against having a “woman boss.”

Martha never thought she would be a director. As far as experience had taught her, directors were men. There were a few female directors that she was aware of, but it wasn’t the norm. Then Robin Phillips “told her” she would be directing her then-husband, Douglas Rain, in Brief Lives (she suspects because no one else wanted to try directing Douglas). Because he was a curler, she used the image of her job, being that of sweeping the ice, so that Douglas could throw the rock. This image has served her as a director ever since. Directing jobs at The Grand and Tarragon followed, and Martha felt she always had to get over the initial hurdle of colleagues accustomed to only working with a male director. Technicians made fun of her if she asked what they felt was a stupid question, or ignored her if the question was smart. If she proposed an emotional choice to an actor (if she felt a character might break down at a particular point, for example), they felt she just wanted them to cry because she was a woman. She thinks that at the time, having a female director in the room “felt like having your mother in the room, which is quite different than having your father there.”

Martha Henry. Photo by Mike McPhaden.

While in her early years as an actor at Stratford Marti created a show with Nicholas Pennell, which they toured around during the off-season. Their tour included teaching, and when Marti feared she didn’t know how to teach, Nicholas told her, “You’ll know more than they do.” She fell in love with teaching and taught more classes in Toronto between Festival seasons. People started suggesting that she should direct, so she began by co-directing with Eric Steiner at Equity Showcase, and then assisting (and co-directing again) with Christopher Newton at The Shaw Festival. By the mid-eighties, Marti was working as a director. She recalls certain male directors joking that she was “taking all the work away” from them—but by and large, she felt supported, particularly by some male artistic directors who helped her start in a significant way.

MM: I believe I told you this story, but there was one act of teaching or directing of Martha’s that predates her story from NTS, because Pam Rogers and I in my first year here [in Stratford] in 1974–

DL: Pam Rogers?

MM: Yes, remember Pam?

DL: Of course.

MM: And she and I went to Martha and said, “We have small roles but we want to work on something Shakespearean. Will you work with us?”

CH: Oh my gosh.

MM: And you said, I think I remember correctly you said, “Well, I don’t really know…” and we said, “Oh please please please!” [laughs] And we did Olivia and Viola in that key scene of Act 1 Scene 5 of Twelfth Night, and we did Yelena and Sonia, I think, from Uncle Vanya.

MH: Oh, that’s right.

MM: And you did. You worked with us which was wonderful.

Diana Leblanc. Photo by Mike McPhaden.

I ask what it was like for them, working with each other in their different roles as an actor or director, or when one is the artistic director, hiring the other as an actor or director. Martha and Diana, in particular, have had a long history working together in their various capacities, and for both the professional relationship has always been overwhelmingly positive.

MH: I can’t think of any problems because we’ve known each other for so long. It just seemed that when I worked with Diana as a director, I trust her implicitly. Implicitly. And we have a wonderful rehearsal hall and a great time.

CH: And do you find that you’re very similar actors and similar directors? Does that help? What’s my question…. Do you find that you think in a similar way and does that help it to be an easy thing as you slip into different roles, that you can trust each other?

DL: I don’t know, you can talk to Marti, but I probably direct Martha less than other directors. Partly because I want to see where she’s going, and I want to be careful about saying something. I watch a lot. I’ve found that when I have been directed by Martha—I’ve never been directed by Marti—but I remember one production especially because I’m re-reading it: Blood Relations. I did things in that production that I would not do with anybody else. I knew that I was doing them partly because they were in Martha’s imagination, which is a pretty capacious one, and I would have to let them find themselves in my imagination. But I was willing to do that because that was somewhere I had never travelled and wanted to.

MH: And when we were doing Long Day’s Journey Into Night, Diana would say very little to me, but at one point I was sitting in this wicker chair and Diana came over to me and she said, “Just rock.” That was all she said. So I sat there and I rocked. And I realised as I was doing it, that that was the key to everything that happened up until then—and for quite a long time after that point—was that rocking. And I thought that was phenomenally brilliant, to give someone one direction like that without saying, “And this is what you’re thinking—”

CH: Yes.

MH: —“and this is what”—

CH: This is why you’re doing it.

MH: —“and this is why you’re doing it.” There was none of that. She just said, “Rock.” And the very activity of it gave me everything I needed to know.

MM: And you need different levels of help or different ways of being spoken to for any different role you play [to CH] as you know, and also the actors you’re working with. Everything changes every time you do it to some extent.

MH: [To MM] And you’re incredibly intuitive about that, too. Because I remember in both Trojan Women and All’s Well That Ends Well, what you seemed to do was to shape the area in which we were to perform. And then we would walk into an area that was created. And within that area, we could do things, but it was quite clear what the area was that we had to live inside.

MM: And don’t you find when you—thank you, thank you for saying that—when you are finished with a production, when you’ve got a good group of actors who are carrying it, and people who are contributing, and it may even be the designer who says something or a prop comes in or a composer may add an element or whatever it might be, and somehow at the end it all comes together, and that’s so exciting. For me, I will always love that moment where it coalesces. But there’s still always a moment where you think, “Oh my god, it’s just awful”—

DL: “Who directed this? Who directed this?”

[laughter]

Christine Horne. Photo by Mike McPhaden.

MM: But then I look at it, or I’ll go back and see a show after a while, and often will look at it and I cannot tell you whether it was Martha or me or that actor, if there’s a certain kind of uniqueness in a moment, who thought of it. I’ve lost complete track—

MH: Yeah.

MM: That is the best—

DL: I can always tell.

CH: Oh, you can?

MH: You can?

DL: Yeah. “I remember asking him to do that. It’s good.”

[laughter]

MM: Well, I’ll admit if it’s a particularly clever thing…

[laughter]

MM: All the worlds. We create little worlds, don’t we?

DL: It’s what we try to do, absolutely. And a universe that will… seduce people, who have come in after dinner or after lunch, who may or may not want to be there.

MM: Yes, exactly. And may be pleasantly surprised, if we’ve done a good job. One has to always hope. But it is, it’s so exciting to… I’ll know I should stop being a director the day I’m not interested in telling the story. I just love that, the idea of it still.

To be continued…

Comments