The Anger in Ernest and Ernestine is actually a play about love

Like Ernest and Ernestine’s relationship, their home is full of quirks.

Through a narrow door frame and down a bright red staircase lies their basement apartment. The fridge door is finicky, a cupboard refuses to close, and a giant furnace occupies the middle of the room.

“The apartment is a character in the story,” director Geoff McBride said in an interview with Intermission ahead of the Great Canadian Theatre Company’s upcoming production of The Anger in Ernest and Ernestine. In terms of colour palette inspirations and props, McBride said the show’s creative team is “embracing everything that’s like Tom and Jerry and The Flintstones.”

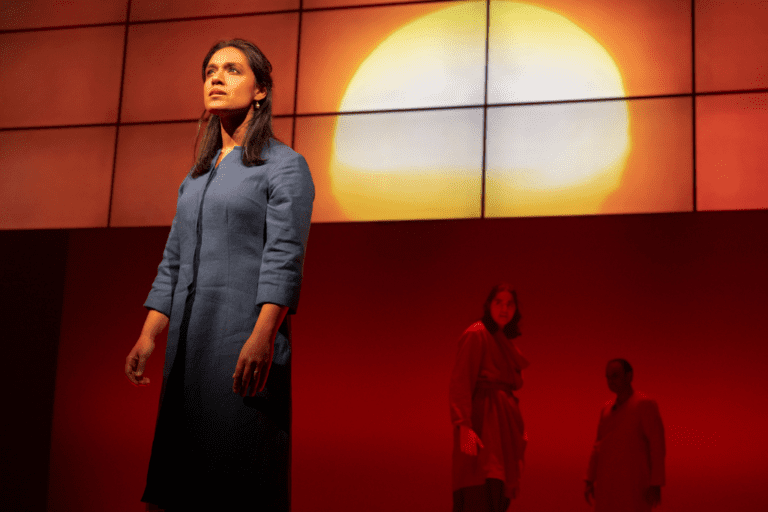

McBride added that Sarah Waghorn’s “very fun” set design is one of the elements of the play that embraces clowning, along with the production’s “superb performers,” Maryse Fernandes and Drew Moore. McBride says he wants audiences to celebrate a great feat of Canadian theatre by having a laugh, but he also hopes the show sparks conversations about audiences’ own lived experiences in relationships.

“You have to be able to not be haunted by who you were, and appreciate where you are now,” he explained. “[As artists], we remind people that they’re human. It’s not always pretty, and it’s not always perfect — sometimes it’s funny, and sometimes it’s sad.”

Emotional juxtaposition is at the crux of the play: “It’s called The Anger in Ernest and Ernestine,” said McBride, “but it is essentially a play about love.”

Originally written in 1987 by Canadian playwrights Robert Morgan, Martha Ross, and Leah Cherniak, The Anger in Ernest and Ernestine follows its namesake couple as they co-exist in their first apartment. Throughout the show, McBride explained, the duo’s imperfect home exposes friction between the characters as their marriage starts to crack.

“It’s all based around the exploration of how we express anger,” McBride said. “To me, the story is about these two people who come together, and discover that while they think they love each other, they don’t necessarily like each other.”

While I’m at GCTC, Fernandes and Moore rehearse a particular scene that involves a tape recorder playing The Yardbirds’ “Stroll On.” The couple quickly breaks out into a heated competition of who-can-out-perform-the-other-on-air-guitar. Competition and spite rumble beneath Ernest’s glares as Ernestine captivates the imaginary audience in the rehearsal room, not noticing the irritation emanating from her partner.

But despite the developing tensions between the onstage couple, McBride insists that the show is a comedy.

“We’re approaching physical comedy first and using that to inform the emotional journey of the characters,” he said.

However, McBride says he’s conscious of the challenges of adapting this nearly 40-year-old play for a contemporary audience.

“There was a school of thought in the ‘90s that men are from Mars and women are from Venus,” McBride said. “I feel some of that was imbued in the script. How we think about gender has changed. We’re trying to think, ‘Is this going to make sense to a contemporary audience?’”

Some adjustments McBride and the production team have explored include “external factors” that provoke Ernest to “act the way that he does,” McBride explained.

“It’s interesting — every time this play has been done, it’s been different,” he continued.

He recalls a first version of the script that ended with the couple aiming guns at one another. In another production over a decade later, he remembers that the guns were still present, but the language was changed. After discussing with playwrights Ross and Cherniak, it was decided amongst the artists that McBride’s version of The Anger in Ernest and Ernestine won’t have any guns at all.

“Attitudes about violence were very different back then,” McBride explained. “Now, introducing a gun in a domestic situation isn’t funny.

“We don’t have an opportunity to address something as critical and as serious as domestic abuse,” he continued. “We also don’t want to make light of it. It is not a joke. So that’s why the play has to be about love, and it has to be about misunderstanding.”

McBride added that this production’s ending emphasizes the characters’ mutual realization that they both lack the qualities required to foster a healthy relationship.

“It’s never about expressing their anger physically against the other person,” he said. “What we’re working towards is that our characters are always within the boundaries of respect.”

To that end, respect and care have been ever-present in the Ernest and Ernestine rehearsal room. The cast has worked with fight and intimacy director Erin Eldershaw, and the production team has a list of “room agreements” that include respecting each other’s pronouns and letting others finish their thought before jumping in with a new idea. At the back of the room is a table set up with snacks, as well as a half-completed puzzle for anyone to continue working on when they need a break.

McBride said cultivating healthy collaboration is part of his philosophy as a director.

“Everything that I say is up for discussion,” he explained. “I’m never right, and I always look to other people in the room.”

He said this approach to directing stems from negative experiences with previous directors, and his own desire to avoid creating similar situations moving forward.

“I didn’t want to be a director, because I worked with so many directors who were horrible,” he said, adding that he particularly disliked the narrow-minded and patriarchal systems he’d encountered on previous projects.

But on The Anger in Ernest and Ernestine, McBride has had the chance to learn new ways of working, from teaming up with his stage manager to working with the show’s designers to deconstruct the technology used to light up an onstage furnace. “I had the realization of like, ‘Oh, you don’t have to run your room like that’,” he shared.

And the learning hasn’t stopped with the art of directing. Part of The Anger in Ernest and Ernestine’s intrigue, for McBride, has been the play’s uncanny ability to conjure up memories of his own past, a quirk of the writing he says is likely to strike audiences, as well.

“This play has tapped into a lot of memories for me about how you think you know what love is, or you think you know what your relationship is, only to discover that […] it just doesn’t work out,” he said.

“People will see themselves in these characters.”

The Anger in Ernest and Ernestine plays at the Great Canadian Theatre Company from September 24 to 29. Tickets are available here.

Comments