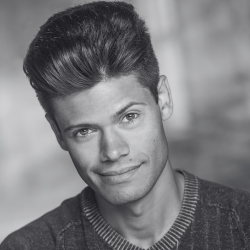

For lighting designer Hailey Verbonac, Indigenous design is in the details

Hailey Verbonac is a trailblazing designer — and budding rap lyricist.

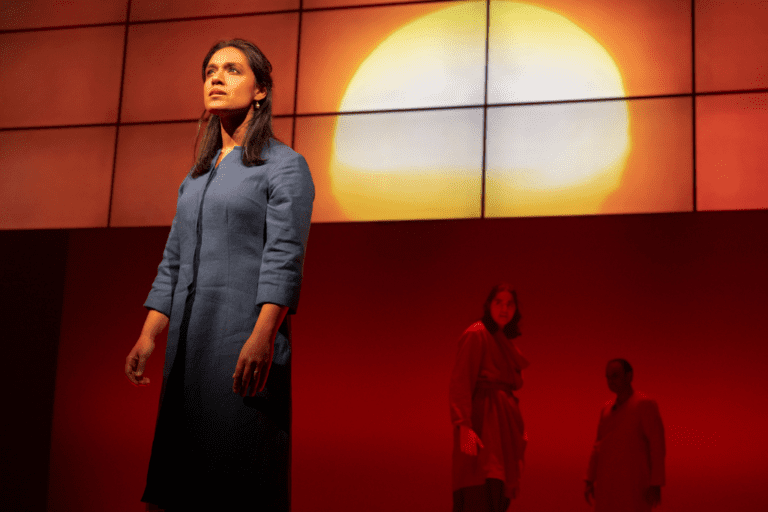

At least that’s the case with regard to his work on Space Girl, a new play by Frances Koncan that Prairie Theatre Exchange is presenting digitally following a live run in 2023. Koncan’s play follows Lyra — the titular space girl — as she travels from the moon to Earth and back again, on a zany quest to charge her phone and revive her waning influencer status. Verbonac was the production’s lighting designer, as well as assistant set and video designer to Andy Moro. The role of lyricist came up unexpectedly.

“Frances loves Succession, the television series,” explained Verbonac. “There’s an episode of Succession where one of the characters does a really awkward rap.” In rehearsal, the creative team decided that one of Space Girl’s antagonists — the brooding influencer Max, who leads an attack against Lyra’s lunar home — could use a rap of his own. “Someone started saying it as a joke, and then it became a serious thing,” said Verbonac. He ended up co-writing lyrics with Justin Otto, who plays Max in the production.

“I asked for co-rap writer to be my primary credit, but PTE would not do that, and that was very disappointing to me,” he joked. “It’s what I’m most proud of on the show, actually.”

Verbonac certainly has a lot to be proud of as a multi-hyphenate designer: the intergalactic world he helped create in Space Girl is gorgeous to behold. When I spoke with him on Zoom, we focused on how he approaches the often under-appreciated craft of lighting.

One of the key responsibilities of a lighting designer, he told me, is to “flow with how the [overall] design is going. Very rarely do I find that lighting leads the thought in design.” Verbonac took his design cues from the colours and shapes in Andy Moro’s set. He decided that for the play’s moon-world, the colours would be “more LED, more neon, more unnatural,” and “the lines…harsher and brighter compared to when we get to Earth.” Verbonac likes to build light renderings in advance of rehearsal, “to paint out how I want things to feel.”

The reference to painting isn’t just a metaphor: Verbonac also has a visual arts practice that directly informs his design work. “I take a very painterly approach to lights,” he told me. “Each moment, each second stage, each light cue is, in my mind, a painting.”

His preferred medium is watercolour. Besides the fact that watercolour “is an easier medium to travel with than oil and acrylic,” Verbonac sees an unexpected connection between watercolour and lighting, “in an inverted way.”

He explained that “when you’re painting with watercolour, the white of the paper is the whitest you’re going to get. You don’t paint white. You paint shadows and you paint around the white, so you have to plan everything for that.”

With lighting, on the other hand, “the darkest the stage is going to get is no light,” he continued. “You’re painting the highlights and bright spots, and everything you haven’t painted is the shadows.”

What does Verbonac think that balance looks like?

“As a designer, you never want to distract from the story,” he answered. “Sometimes, what would be the prettiest lighting isn’t always the best for the piece.” He used another painting metaphor: “this really cool little tree right here is making the painting worse, so we’ve got to take out the tree.”

Just as important as this overall balance is a commitment to detail and the designer’s own sense of integrity. “The details, they’re for me,” Verbonac said. “I know the audience will never see it, but for the completion of the painting in my mind that’s important.”

Verbonac is not just an accomplished artist; he is one of a precious few Indigenous designers currently working in so-called Canadian theatre. Of Afro-Indigenous (Red River Métis) ancestry, Verbonac grew up in Inuvik, Northwest Territories: the third largest town in the region and, as Verbonac informed me, “home of Canada’s most northern stoplight.”

“I think tourism should sponsor me”, Verbonac joked. “They disagree with me so far, but we’ll see after this [article].”

Verbonac’s first exposure to theatre was in Grade 11. “I watched a bootleg of Cats,” he told me, “and I thought, ‘I think I might like to do that.’ I was entranced.” After completing an undergraduate degree in biology at Mount Allison University, with a focus on marine botany and a minor in drama, Verbonac entered the National Theatre School of Canada’s production design and technical arts program.

At the time, Verbonac was one of the first Indigenous students in the production major. (NTS has since launched a program called New Pathways, in collaboration with Native Earth Performing Arts, to bring more Indigenous students into technical theatre.) He is also one of a relatively small number of Indigenous designers in today’s theatre landscape.

“There’s a real dearth of Indigenous designers,” said Verbonac. “For lighting and video I can think of maybe five.” He went on to stress the importance of Indigenous representation in theatre design, particularly because of the cultural specificity of so many Indigenous works.

Specific cultural knowledge “can be enriching for the piece and it can be more efficient, it can save time,” Verbonac continued. He cited a recent example from his own practice: “There’s a workshop I’m involved in right now, that’s in the Northwest Territories…I was talking with the director and we were able to just have deeper conversations, in terms of detail…The cultural references had just eased that, because it was a location-specific piece about a location not many people are familiar with.”

With that said, Verbonac was careful not to paint the term Indigenous in broad strokes.

“Even me, I come from a very specific place, and my parents moved there,” he told me. “So I’m Indigenous and of Inuvik, but I’m not Indigenous to Inuvik. So I’ve got some cultural references from growing up in Inuvik, and I have some cultural references from my ethnicity.

“But,” cautioned Verbonac, “I did a show in Kamloops that was about Secwepemctsín language reclamation. [Echoes of the Homesick Heart by Laura Michel, at Western Canada Theatre in 2022.] I didn’t know anything about that.”

“There’s so many cultures within [the category Indigenous] that I’m not familiar with that I think, the more the better!”

In both design and representation, it’s the details that matter.

Space Girl streams digitally through Prairie Theatre Exchange until January 28. Tickets are available here.

Comments