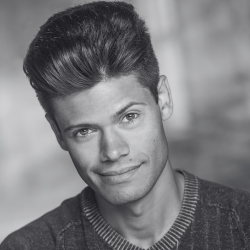

For Lessons in Temperament’s James Smith, pianos are partners in vulnerability

For musician and theatre-maker James Smith, pianos make powerful scene partners.

Certainly that’s the case in Lessons in Temperament, the autobiographical solo piece Smith created in collaboration with Outside the March’s Mitchell Cushman. For the duration of each performance, Smith tunes a piano in front of a live audience. At the same time, he shares stories of his family’s experiences with neurodiversity, including obsessive compulsive disorder, autism, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia. The act of tuning soon reveals itself to have striking parallels to Smith’s lifelong journey with mental health.

Lessons in Temperament is currently on tour in Ontario: its next stop, presented by Brampton On Stage, will be the Rose Studio Theatre. When I chatted with Smith on Zoom about the tour, it became clear that, though Lessons in Temperament is billed as a solo show, Smith is far from alone onstage.

The piano is “sort of a filter,” explained Smith. “You know how actors really love a bit of busy work to do sometimes? An actor will… eat, or make tea, or clean [as part of their movement onstage], and that can unlock something in the brain as a performer. You’re almost filtering [your performance] through this task… It splits your brain in an effective way.”

Tuning isn’t only a practical distraction for Smith. The autobiographical nature of Lessons in Temperament requires immense vulnerability. By tuning a piano with care, Smith can extend that same care to his own wellbeing onstage. “The act of tuning… allows me to find a good balance in terms of how deep I go into certain stories,” he shared. “There’s a fine line sometimes of going too far in and living it too hard, because I have to do it night after night after night.” The piano helps Smith find that balance.

“If I’m having a difficult moment during the show,” he continued, “I can just take a moment and tune a few strings and then get back to it. So in that way it’s very much a scene partner… that can sort of improvise with me night after night.”

By this point, Smith has had his share of scene partners: he’s been performing Lessons in Temperament in various forms off and on since 2016, when the show premiered as part of the SummerWorks Festival. At first, Smith performed the show while tuning pianos in people’s living rooms — a different one night after night.

In fact it wasn’t until Lessons in Temperament’s third run — at the Signature Theatre in New York in 2017 — that Smith had to do multiple shows on the same piano. “I had to develop this habit [of]… waiting for the audience to leave, and then sort of painfully knocking the piano back into [an untuned] state,” he told me.

By this point in the show’s life, Smith has learned that some pianos require more care than others. “In those first couple runs in Toronto, I got into some hairy situations with a couple pianos where I was like, ‘This is going to take hours,’” said Smith. “If a piano hasn’t been tuned in three years, fine, like I can do the show. If it hasn’t been tuned in 20 years, that can become a serious issue live.”

It’s happened before. Smith remembered showing up to a church for a show in 2016, only to find that the piano “hadn’t been touched in decades…I realized that was going to keep happening,” he said. These days, Smith told me, he’ll “visit the piano a couple of times before the show day [if necessary], just to slowly get it higher in pitch and closer to the point where I [can] do a performance. I’m not going to catch myself accidentally doing a three hour show for people.”

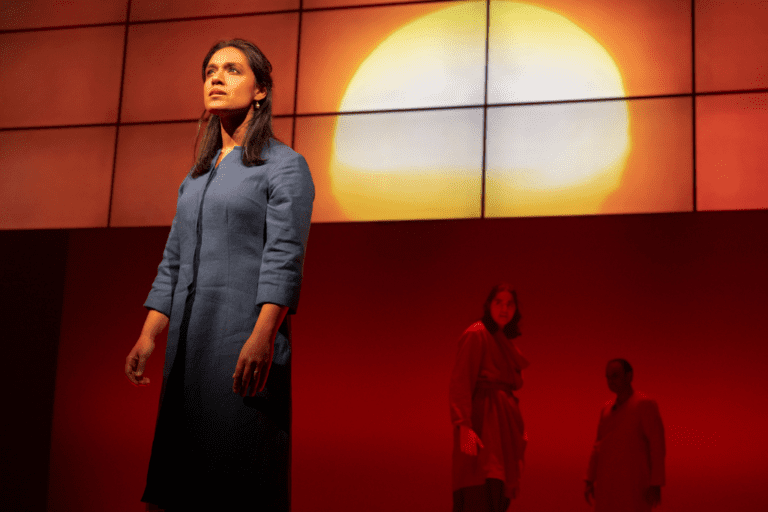

During the height of the pandemic, Smith and Outside the March created a film version of Lessons in Temperament. For the film — which is available to stream — Smith visited empty theatres across Ontario to tend to their neglected pianos. Now that the live show is back on the road, Smith has been delighted to reconnect with another set of scene partners: live audiences.

“Every show I [get] to feel the glow of an audience and the completion of the play in a way that I didn’t get while making the film every day,” said Smith. He pointed out that Lessons in Temperament still doesn’t have a fixed script, but rather a list of key points he has to hit for each performance. This flexibility means Smith has much more freedom to react to each unique crowd.

“I remember stopping the show because someone really wanted to tell a joke… about a bass player,” Smith laughed. “I like the idea that an audience member would feel comfortable enough to tell a joke during my play. Theatre can feel like a very sacred and reverent space. I like the idea of knocking down some of those walls a bit, making people feel more comfortable.”

If Smith is knocking down walls between himself and the audience, he is also doing so with regard to how theatre treats the subject of mental health. “When I wrote this piece,” he reflected, “I felt like mental health was just starting to enter the common lexicon in theatre. The examples I had personally experienced in theatre of people engaging with…mental health and mental illness [were] a bit careful and almost scientific…and good! Like not bad.”

With that said, when Smith began to write Lessons in Temperament, he realized that he could offer “a point of view around mental health and autism and schizophrenia and bipolar disorder and obsessive compulsive disorder… that is not sensational in any way. It’s just life, it’s just normal, and it’s utterly unscientific. And it’s not careful. It’s very honest.”

Today, Smith said he sees “people in the theatre engaging with these things a bit more easily” — something he was careful not to take credit for. “I hope people can be honest and share their experiences without fear,” he told me. “That basic fear within us of shame, right? But also fear of any kind of retribution from the audience of like, ‘you shouldn’t be talking about these things.’

“I feel like that’s just lifting and lifting and lifting,” he said. “I feel the freedom.”

Lessons in Temperament runs at The Rose Studio from February 8 – 10. Tickets are available here.

Comments