In the darkest months of Yukon winter, it’s all about the Sun Room

“It’s unseasonably warm in Whitehorse this evening,” the pilot quips over the plane’s loudspeaker. I check my phone as we taxi toward the airport: -5 degrees Celsius, with a dip to -13 in the hours to come. Not exactly balmy.

I polish off the treat handed to me moments ago by a flight attendant; Air North, I’ll learn, is beloved for its dedication to complimentary warm cookies, buttery morsels handed out in bakery-style paper bags. It’s a nice way to finish a flight, a gentle squeeze of chocolate and oats.

These final moments of my flight from Vancouver are all the introduction I’ll need to the mythology of Whitehorse: It’s cold here, very, but the people take care of each other. They see the value in a warm cookie.

I’m here for a week in January as a guest of Nakai Theatre, a hub for theatrical experimentation and outside-the-box programming in Canada’s westernmost territory. While here, I’ll be leading workshops on theatre criticism and music journalism, and I’ll be taking in some of Nakai’s winter programming. It’s my last Intermission assignment before starting as the theatre reporter for the Globe and Mail.

At Nakai, January is synonymous with Pivot Festival, a four-week celebration of creativity and sunlight best exemplified by the Sun Room, a celebration of sunlight that offers locals and visitors alike the chance to escape from the dry darkness of the northern winter. On the drive from the airport to my hotel downtown, I’ll hear all about the Sun Room, its waitlists and its toasty incandescent lighting. I won’t understand until I see it, though, just how lovely a colourful room can be, a miniature world of sunlight and tinsel sequestered from the northern winds.

Norah Paton, managing artistic producer of Nakai and my roommate when I lived in Ottawa, drops me off at the hotel, a relatively nice Best Western with a fireplace in the lobby and crisp white sheets on the beds: Home for the next week. Norah hands me a welcome bag filled with stickers, cans of craft beer, and pamphlets about the local nature. I giggle at a booklet advising me of the territory’s various bat populations, and wonder with some amusement if I’ll be encountering many of the creatures while I’m here.

I drift to sleep and dream of bats. I can still taste chocolate on my tongue.

O thou invisible spirit of poetry

You’ve most likely heard of a pub crawl, in which you and a group of strangers hop from bar to bar, sampling drinks and sharing stories.

But what about a poetry crawl?

On my second night in Whitehorse, I’m dressed in approximately 10,000 layers, including two sweaters, a cashmere scarf, and my insulated L. L. Bean boots. A pink piece of nylon is tied around my backpack, indicating I’m part of the first group of the poetry crawl, a thrum of people speaking more French than I’ve heard since moving to Toronto. Around 5.5 per cent of the Yukon population speaks French regularly, but that number is larger in Whitehorse due to its status as a territorial capital with a high concentration of federal workers.

Pivot Festival has run since 2009, and is a midwinter gathering for artmakers in Whitehorse and beyond. Nakai prides itself on producing “theatre that can only be made here,” and over the course of Pivot, I’ll observe that to be true — the landscape and the art are one, impossible to separate from each other.

We inch along the Yukon River, stopping periodically to hear poems from local writers, hand-picked by esteemed Whitehorse poet Peter Jickling. Over the course of an hour, we hear verses about everything from suicide to coyotes; from walking the dog to finding the body; from crowded coffee shops to echoing forests. Each poet approaches the form totally differently, positioning themselves in surprising spots along the riverfront. Small changes in the landscape seem to harmonize with the words — a condo terrace becomes a Romeo and Juliet-style balcony. A bench becomes a stage. A tiny shack becomes a podium, the vast blackness of the river swirling as the words spew out.

Mittened hands clap for each poet. It’s an applause unlike any I’ve ever heard, dampened by the gloves. The polite thuds echo in the stillness of the riverfront trail.

The crawl concludes with a fire pit and bottomless hot chocolate. We chat with our fellow crawlers; I get to meet Nakai’s artistic director Jacob Zimmer, who with Norah will be my guide to the city and its people this week. I feel the wind cut through my jacket and I clutch my drink, slurping the cocoa and turning my face toward the fire, dodging sparks as they flutter from the pit.

On the walk home, I listen to a playlist of old favourites — quiet, plucked-guitar meditations on solitude like Dermot Kennedy’s “For Island Fires and Family” to Honeywater’s “Old Eden.” I note the crunch of snow under my boots, the satisfaction of good tread and cracked ice.

Then I look up.

A stripe of green materializes across the sky. I hold my mitts in the air, trying to block out the streetlights. I need to know what I’m seeing is real.

The green stays, with whispers of purple and blue. Stars twinkle against the endless void.

And just like that, I’ve seen the Northern Lights.

Visible in the territory from August until April, the aurora borealis is everywhere here — on tourist merchandise, in poetry, on street signs. For locals, seeing the colours on the walk home from an evening performance would be normal, a part of living in Whitehorse as commonplace as 18-hour nights. For me, the lights are a kept promise, a legend made real. I stand transfixed as the green glow smudges across the sky.

Look Up, and other wonders from the Sun Room

At Pivot Festival, it’s all about the Sun Room.

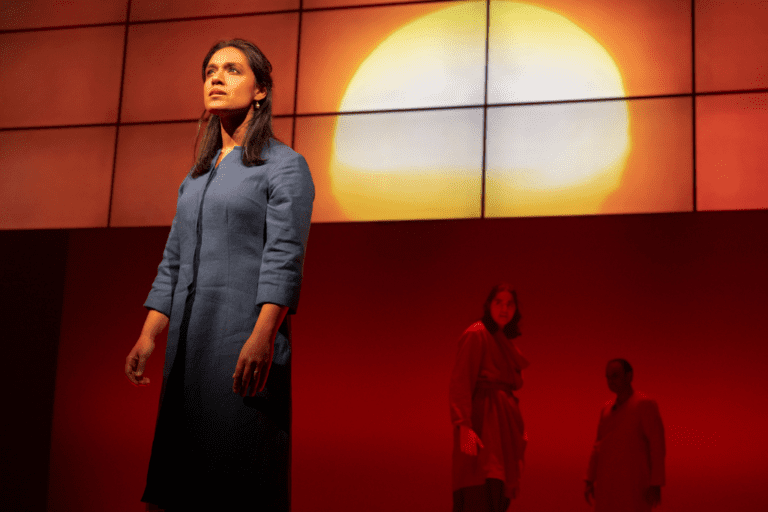

Designed by multidisciplinary artist Tara Kolla, the Sun Room occupies about half of Whitehorse’s Old Firehall, a flexible performance space in the city’s downtown core. During Pivot, the room becomes alive with colour and texture — metallic streamers waft from the ceiling, and dozens of mismatched chairs and tchotchkes decorate the perimeter of the space. On the floor are rolls of astroturf — Jacob jokes about the artificial grass being a hot commodity in a national theatre landscape infatuated with Sarah Delappe’s The Wolves — and around the room are painted props, wooden boards that add to the feeling of being in a curio shop.

But the room’s crown jewel is its sun, a massive structure made of tent poles and repurposed potato chip bags, turned inside-out so their aluminum insides can glimmer. Incandescent theatre lights beam down on the bags, making the room feel warm but not overly stuffy. The Sun Room is a marvellous reprieve from winter. “Very low intensity immersive theatre,” Jacob calls it.

In my week at Nakai, I spend lots of time at the Sun Room, where much of Pivot’s indoor programming happens. A curated night of performances, called Short Works for Quiet Nights, features poetry and prose readings as well as a musician. A mid-afternoon dance party is kid heaven, and I watch as hordes of children frolic in the installation, dancing to “Shake It Off” and chasing each other around cardboard trees.

But it’s Look Up that transforms the space even further. A performance for children created by local physical theatre company Open Pit, Look Up asks its audience to lie on yoga mats, their heads resting on pillows pilfered from the Sun Room. A screen hangs from the ceiling, protected by delicate curtains, and on the ground is an old-fashioned overhead projector, along with containers of sand and water. (For Toronto readers, the setup isn’t dissimilar to Pencil Kit Productions’ I love the smell of gasoline, save for the lying-on-our-backs of it all.)

Over the course of 40 or so minutes, we see two short stories play out on the screen, narrated by Alita Powell and Geneviève Doyon. The kids at my performance eat up the tales about a sad little girl named Juniper and a lost dog named Copper, and they audibly gasp when shadow puppets disappear into paper chasms and bubbling seas. It’s a dandy piece of children’s theatre, though I wish there were three stories rather than two — at the 40-minute mark, I wasn’t quite ready to leave these whimsical worlds behind. When I step out for a coffee, the kids from my performance linger behind, tracing their fingers through pink sand.

That coffee comes from Baked Cafe and Bakery, where I also sample some of the best doughnuts I’ve ever tasted. A coconut crème brûlée confection quite literally changes my life. At Baked, I spot the folks who attended my workshops, and they say hi, ask how I’m enjoying the territory, supply recommendations of things to do without me needing to ask. They ask what I thought of Hamilton when I reviewed it for the Toronto Star a few years ago. It’s a level of small-town friendliness I’ve not experienced before.

I’ll come back to the Sun Room plenty of times on my visit to Whitehorse, contentedly reading a book under those magic lights. Whenever I walk by the Old Firehall, I sneak a peek through the windows at the crafted flowers and shiny detritus. I’ll miss it when I get back to Toronto.

Skiing, sightseeing, springing

Of course, it wouldn’t be a trip to Whitehorse without a few excursions to appreciate the landscape.

One afternoon, following a workshop with a theatre class at Yukon University, Norah and I take to the hills for a short cross-country skiing lesson. She’s a marvel as she glides through the snow, and extraordinarily patient with me as I stumble over my skis. I don’t leave the lesson expecting to ski in the Olympics any time soon, but I do feel like I’ve accomplished something, and I revel in the glow of being able to do something a little better than I was able to do it an hour ago.

Another day, Jacob takes me in his Subaru to Carcross, a tiny outpost between Whitehorse and Alaska. Decrepit buildings imprint themselves onto my mind — churches affiliated with former residential schools and miniscule post offices that look over an enormous lake. In the summer, Jacob says, Carcross is a haven for tourists, with functional hotels and gorgeous views. It’s beautiful in January, too — totally pristine, with long stretches of undisturbed snow in every direction.

A dog appears in the road on our way back to the highway, frolicking in the cold. The huskies I meet in the Yukon, caked in slush and salt, are the happiest I’ve ever seen.

On the final night before I head home to Toronto, I join Norah, Jacob, and Valerie Herdes, another Nakai employee, on the road to the hot springs. The sky gets darker as we dart away from the city, and the stars get brighter, piercing the velvety dark.

In the hot springs — luxurious hot tubs blanketed in steam and flanked by ice caps — we solve the problems of the world, trading stories of Canadian theatre from coast to coast. Norah and I reminisce on Ottawa, which, despite being much larger than Whitehorse, faces many of the same problems in its relatively small theatre community (including a dearth of high-quality theatre criticism, not enough professional opportunities for most artists to make a living, and an incestuousness that can make the industry feel even more cramped than it already is).

But Whitehorse has a lot going for its artists, too, Norah tells me — there’s a healthy amount of arts funding per capita, and the close-knit community makes it easy to call in a favour as needed. Friends often serve on each other’s boards. Nakai will co-host PACTcon, the conference for Canadian theatre professionals, in 2026 — it’ll be a great chance for artists to experience and take inspiration from Whitehorse’s generous, pocket-sized theatre community.

We soak in the water, our hair freezing into abstract shapes as we imagine the future of Canadian theatre. It’s a perfect last night in the territory.

When I board my flight back to Vancounver the next morning, I’m worried I’ll be cold — it’s awfully chilly on the plane.

But when I settle into my seat, I think of the Sun Room, the long streams of light against the oily husks of the chip bags. My fingers warm, then my toes. I drift asleep and dream of mountains, toasted gently by a theatre full of stuff.

Aisling Murphy travelled to Whitehorse courtesy of Nakai Theatre.

Comments