Raising Tough Questions with Every Day She Rose

“So who wins the oppression olympics?” I ask directing duo Andrea Donaldson and Sedina Fiati. There’s laughter, then a snappy comeback from Fiati: “Nobody.” Every Day She Rose is making its debut with feminist theatre company Nightwood Theatre. The piece is inspired by the 2016 Black Lives Matter (BLM) protests during Toronto’s Pride, and the political strife is explored through the lens of two friends who exist at the intersection of the same conflict. What should’ve been a day of celebration turns into picket signs – and picking sides.

When interviewing playwrights Andrea Scott & Nick Green, Donaldson was intrigued. Their first meeting was through Nightwood’s Write from the Hip program for emerging playwrights. Part of the company’s mission is to provide an “essential home for the creation of extraordinary theatre by women.” Donaldson remembers “it was fun and cheeky that it was a co-writership with a guy.”

Scott and Green had already come up with a full first draft, explains Donaldson; at the time it was a fictional piece between these two roommates who go through this journey. “Through our time together, hearing what they wanted to do with the piece, I became intrigued by how a queer white guy and straight Black woman were going to co-write it. How they were writing for each other’s voices? [Why do they even?] Would they get into fights? Was it copacetic? How did they actually make it? In probing them to go a little deeper into their own selves, and take on some more dangerous questions, they ended up cracking open the play they had written, and infusing themselves as playwrights into the text as well.”

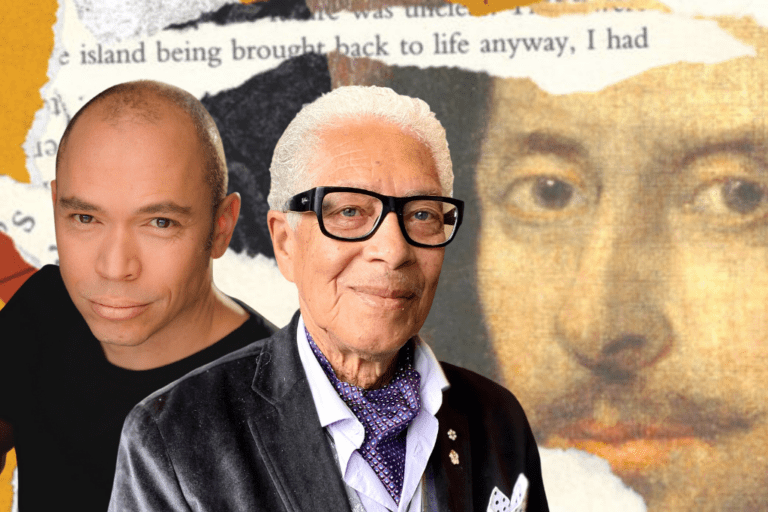

Nick Green and Andrea Scott in rehearsal for Every Day She Rose. Photo courtesy Nightwood Theatre.

Kelly Thornton, who was the artistic director at the time, programmed it for the current season. At the end of the Write from the Hip process, actors read the work aloud in a public reading. “From that moment Kelly was like yeah, we’ve got to have this on stage. And then tasked me with finding another director for the piece, and that’s where Sedina came in.”

While this marks her directorial debut, Fiati has over a decade of professional experience, doing the behind the scenes work in creating theatre about the stories of women of colour. “Andrea asked me to come on board to direct the piece with her and try a co-directing model. People thought that I would be a good fit for director, but knowing that I don’t have a lot of experience in directing, [Andrea] was like “let’s direct this together.” It also mirrors the cowriting of Andrea and Nick. I read through the script and thought it was very timely.”

As an intersectional woman of colour, Fiati felt “some type of ways” about the protest. “It caused certain reverberations between the communities. I remember having heated conversations with mostly white gay men on Facebook, and some in-person too. I also joined the Pride Toronto general membership that year. So it was a real heated year after that. Pride had already started to do some consultations with the Black community, about what BLM had brought up, and that was a part of what was in the demands. Then they were kind of waffling about what to do with the police, and then somebody made sure that it was added to the Pride agenda, because it hadn’t been on there. So that everything that BLM asked for would actually happen because there was a danger that it wouldn’t. The next year it wasn’t revisited, and this year it almost came back. What they did, and what they were asking for, is something that the queer community as a whole is still grappling with. It comes with a whole 30-year history of lack of inclusion of people of colour within pride.”

Sedina Fiati and Andrea Donaldson in rehearsal for Every Day She Rose. Photo courtesy Nightwood Theatre.

Fiati cites Our Dance of Revolution by Philip Pike as part of that history. The documentary traces Black queer activism from BLM and goes backward. “People of colour as a whole have always been a part of the queer community, but they’ve often felt excluded. It’s an exclusion that goes both ways. Someone in the movie said, “Am I a Black person part of the queer community, or am I a queer person part of the Black community?” As queer movements have been moving forward down, I feel like people of colour have really had to dig down, and beat the drum and say we’re here, always, because there is a danger that we are not included. BLM said we’re not just going to march in this parade and act like everything is okay when it truly was not. We’re going to take this moment to shine a light on issues that have plagued us forever.”

I suggest to the pair that being Black is the same as being gay, which both emphatically reject. “You can be both, then where are you?” quips Fiati. “I think there’s definitely a shared history, people who are oppressed can definitely relate to other people who are experiencing an oppression. But what happens in the queer community, is that white gay men can oppress pretty much everybody else, even though they are experiencing oppression — and those things can happen side by side. But we both know these things happen on a gradient. That’s why the theory of intersectionality is so important. There are people who are going to experience even further marginalization the more that they sit at the intersection of marginalized identities. A lot of white gay men don’t get that yet. Some do. “We got what we wanted, Pride is a celebration, Pride is a parade, I still get bullied occasionally. What are you complaining about?”

Fiati offers a breakdown of Every Day She Rose: protagonists Cathy-Ann and Mark (played by Monice Peter and Adrian Shepherd-Gawinski) are trying to have a friendship; however the issue of racism comes up, and Mark doesn’t really have the analytical tools to be able to relate to Cathy-Ann. At the crux of it all, this ignorance breaks up their friendship. “Who’s really winning in that situation, because they can’t be friends anymore? Who really wins when we exclude people? We think we’re winning, but we’re not, we’re just losing out on voices because we’ve left people behind.”

I point out that as director, Fiati has a fantastic opportunity to have her voice heard. ”I’m not telling anyone what to do, we collaborate. Even thinking of Nightwood as a feminist organization and how Andrea approaches how we work with everyone; we ask a lot of questions. They have what they need already, and we’re just filtering all the ideas trying to shape it into something. I think a lot of people in our society want leadership because they want power. They want power over, and I’m more about power with. The position of director within our hierarchical colonialist framework has been given a certain reverence. I don’t think that’s helpful. It keeps a lot of women from doing it, and women of colour feel incapable. But actually no — if you can gain the skills you can do it.”

Monice Peter and Adrian Shepherd-Gawinski and rehearsal for Every Day She Rose. Photo courtesy Nightwood Theatre.

Fiati remarks on how her own intersectionality is affecting the work she receives. “What’s been happening lately, because I’ve been so outspoken about who I am, it is now something that people hire be because of. I love it, it’s a really good thing. I identify as a woman, I’m Black, but the fact that I’m also queer, people are like “I’m looking for this.” And it’s mostly been women who’ve been seeing my intersectional identity as a gift. As something that is an asset. In terms of mainstream commercial work, it means I’m maybe not doing that, and that’s okay. I’m very principled in what I want to do, and I’m very clear in my vision. I’m Black, I’m queer, I’m out, I’m an activist, and those are all things I bring to the work.”

Fiati stoically rejects the idea that Pride is fixed now. “The grappling continues. Pride, because it represents a lot of different people, there are ongoing discussions and arguments and disagreements. That is the foundation of Pride. And those types of things are what led to the Dyke March, and Trans March has become a lot more prominent in recent years; again, people continuing to advocate for themselves. A lot of POC communities are not feeling Pride as an organization, and that it’s becoming too corporate. And there is an alternative Pride that has popped up called Bricks and Glitter, and in other cities, there are other prides. Montreal has three different prides. Maybe that’s just needed. Maybe there can’t be one organization that represents everybody. Especially if it’s becoming more corporate. The more corporate things become the more watered down they become like a necessity because they are trying to appeal to the most people. And the more you do that, the more you will alienate the most marginalized of folks. We’ll see where the future is headed; where I see it, people are going to start doing their own thing, independent of Pride, because I don’t know if it has the capacity to hold everybody.”

Comments