Storytelling Through Song

Four years ago, I was hired to be a part of the Stratford Festival company. That year, their musicals were Fiddler on the Roof and Tommy. For a Jewish female whose performing roots are in musical theatre, a production of Fiddler on the Roof is like the Holy Grail. If the Stratford Festival was ever going to hire me, it seemed logical that it would be for the most famous musical about Jews on planet Earth.

I didn’t get cast in Fiddler. Because I was going to be out of town at the time of the callbacks, I did a video submission. But those are tough to nail, especially when you’re up against a bunch of very talented people who are actually auditioning in person. It seems a bit defeatist and dramatic, but I just kind of resigned myself to the fact that if it wasn’t gonna be Fiddler, I wasn’t gonna work at Stratford. Ever. Oh well.

And then, at the beginning of November 2012, I got a call to come and audition for Stratford for the coming season. For Fiddler? I asked. No: For The Merchant of Venice. An immediate replacement was needed for the role of Jessica, Shylock’s daughter. I of course accepted the audition, but I did so with a healthy dose of self-doubt and basically no expectation whatsoever that I’d get hired. The last time I’d touched Shakespeare was in university, when I was taking a course in phenomenology in Shakespeare’s work (don’t ask me what that means now), and the last time I’d performed it was when I was fifteen. Antoni Cimolino and Beth Russell thankfully believed in me more than I did, and I will eternally be grateful to them. I ended up getting the part, something I still marvel at and am deeply humbled by.

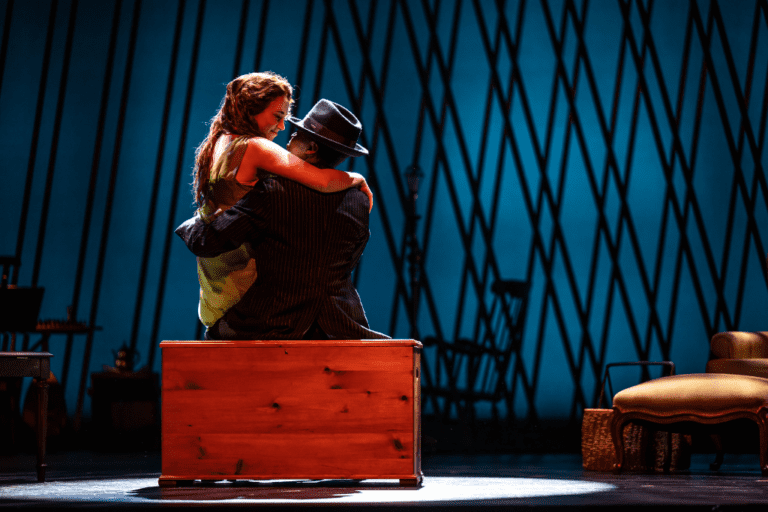

Sara Farb as Jessica and Tyrone Savage as Lorenzo in The Merchant of Venice. Photo by David Hou

So, apparently, I was in the acting company. I felt enormously out of place. It’s normal for any performer to feel like a fraud at some point (or, let’s be honest, at most points), but the sensation was particularly overwhelming for me, as someone who had until then identified exclusively as a musical theatre performer. It didn’t help either when people would ask me what I was in: “So you’re in Fiddler, and what else?” I’d have to explain that, actually, I wasn’t in Fiddler, but two Shakespeares and The Three Musketeers. I had always thought of my acting and singing skill sets at basically the same level, but I did my best singing when I was acting, and vice versa. How could I establish myself at this company, with so many impossibly talented people who had training and more experience in classical theatre, without being able to sing? It was a weird feeling.

Eventually, my confidence grew, thanks in large part to Antoni and Beth, but also to Tim Carroll, who was directing me in Romeo and Juliet, and whose approach to Shakespeare busted open a universe of possibilities for me as a performer, and to Sara Topham, whom I was understudying (she was playing Juliet), and whose skill with Shakespearean verse was so elegant and so inspiring. Suddenly, I was starting to identify as a classic theatre actor. This newfound identity helped when I was asked to audition for, and ultimately be in, King Lear and The Beaux’ Stratagem for the following season. I had a handle on the text that I could not have hoped for a year before.

Sara Farb as Cordelia and Colm Feore as King Lear in King Lear. Photo by David Hou

The cost to all of this, though, was that I missed singing. Immensely. I’d go and watch the incredible musicals at Stratford, or Shaw, or Acting Up Stage, and feel a deep longing for the kind of performing I wasn’t doing. I was vocal about my interest in being in a musical at Stratford, but it wasn’t until this season that the right opportunity arose. To my great joy and excitement, I was cast as Petra in A Little Night Music, one of the most beautiful musicals ever written, with a phenomenal cast and creative team. After four years, I would not only be doing a musical again, but I would be doing this musical.

In the first week of March, we started rehearsals for A Little Night Music. As day one approached, I was growing more and more excited, but was also experiencing something I hadn’t expected: I was scared. For three seasons, I’d worked very hard to be the best actor and company member I could be. My focus lay in finding clarity in classical text, or ensuring my diction was on point, or making sure I was projecting enough. My storytelling through song, I realized, had gotten a bit rusty as a result. And it turned out, so had my music learning skills. For the first few rehearsals, my brain was inexplicably incapable of hearing basic music intervals. Yes, Sondheim writes difficult music, but I could usually figure something out after a few failed attempts. This time, it was taking an eternity and I was very frustrated. Also—and this is an issue I find sort of disappointing—there’s generally a bit of a gulf between the acting and musical companies at Stratford. You’re often either in one or the other. Though there’s lots of crossover this year, I couldn’t help feeling somewhat out of place. And I faced something of an identity crisis. I was finally back in my comfort zone, but it wasn’t as comfortable as I’d remembered. Before, I was a musical theatre actor masquerading as a classical actor; now, it was the other way around.

From left: Alexis Gordon as Anne Egerman, Sara Farb as Petra, and Ben Carlson as Fredrik Egerman in A Little Night Music. Photo by David Hou

In the show, I sing a song called “The Miller’s Son.” It comes about fifteen minutes before the show ends, sort of out of nowhere, and is a commentary on the events and the themes of the show from my character’s perspective. “The Miller’s Son” is a difficult song to crack. Like most of Sondheim’s songs, steeped in emotional complexity and squeezing every ounce of linguistic possibility out of every phrase, this one is actually more of a monologue, and a challenging one at that. Maybe if I thought of the song in that way, rather than as proof that I could do more than stand and speak at Stratford, I would feel more comfortable; less pressure. With that in mind, I set to work on the song. It helped. But not entirely.

Recently, we had our sitzprobe, the first time the orchestra (which, for our production, is unusually large and tremendous) and the actors play and sing together. Sitting there in awe of what I was hearing, the glory of this score played to its fullest potential, I finally understood what a disservice I’d been doing myself, trying to figure out where exactly I fit in on the actor spectrum at this place. Doing a musical doesn’t make me a musical theatre actor, just the way doing Shakespeare doesn’t make me a classical theatre actor. There is music in everything. Boiling myself down to what show I’m doing at the time only exacerbates the already inevitable self-doubt that comes with beginning the next new thing. It’s all an accumulation. And if someone feels confident that I can do a job and hire me for it, why should I doubt them? It’s my job to prove them right.

Comments