How SummerWorks confronts a theatre industry steeped in hustle culture

Hustle culture! Grindset! Workaholism! Whatever you want to call it, artists today are often expected to operate in a state of perpetual labour. This year’s SummerWorks Performance Festival takes aim at these demands through a different approach to programming. Rather than glorifying the endless slog frequently required of creative types, the 2024 festival promises to highlight the value of downtime as part of the creative process.

The self-care-centred program includes Summer Break, a one-day, mid-festival program of works focused on the idea of “rest.” The series includes a conversation with longtime festival fixture Elder Duke Redbird, who will discuss ideas of relaxation and reflection; a film installation courtesy of Sujit Vaidy; and a meditation on composting courtesy of Thomas McKechnie, along with other events.

Themes of rest and recovery also percolate throughout much of this year’s performance slate. For choreographer and visual artist Camille Huang, taking breaks is critical to the creative process. A recent graduate from L’École de Danse Contemporaine de Montréal, Huang is currently learning to balance the demands of the industry.

“Instead of seeing my work as a product that I have to sell to as many people as possible, I’m shifting to see it as being about building relationships,” Huang said in an interview. “For me, rest is really about sustainability and figuring out how I can continue doing the work on an ongoing basis.”

Huang’s Slug Meal (arriving at the festival after a successful run at Montreal’s OFFTA) mixes movement with text in Mandarin, to explore conceptions of immigrant food as distasteful. Co-presented with Dancemakers in association with Buddies in Bad Times Theatre, the hyper-physical solo examines ideas of purity and belonging through a loose narrative about a performer haunted by the manifestation of a swallowed slug.

The program also includes Too Dirty to Clean, created by puppeteer-performer brawk hessel along with director-dramaturg Harri Thomas. The piece addresses the financial challenges faced by disabled artists through an exploration of hessel’s experience as a recovering addict who occasionally works as a house cleaner to make ends meet.

“When I talk to people outside the performance sector about working on a show, it’s often passed off as if you’re not really working,” hessel told Intermission. “Operating within an attention economy, there’s a feeling that you constantly need to be making content. But for me, rest is often part of the work, even though it’s not immediately producing anything.”

“As far as our sector goes, there’s this idea that how busy you are is a reflection of your values,” added Thomas. “We also tend to emphasize a person’s career over the body of work they’ve produced. There are certain things that we can do at a community level, particularly when it comes to resource sharing. But we also need to consider the fact that we operate in a scarcity environment where we’re so focused on individual shows that we often neglect the larger ecology.”

On the lighter side of things, there’s Monica Bradford-Lea’s Beth-Anne, a family-friendly physical comedy about a girl who decides to transform into a horse. Co-created with Theatre Newfoundland Labrador artistic producer Nicholas Leno, Bradford-Lea began developing the show in 2018 through opportunities with undercurrents and the Fresh Meat Festival in Ottawa. Working on and off over a span of six years, Leno and Bradford-Lea were able test out various ideas and interact with different types of audiences over a comparatively long stretch of time, allowing more space for reflection between working periods.

“There needs to be a mindset shift in our field around work and rest,” Bradford-Lea said. “When we reject the need for rest, we reject part of what it means to be human. This conversation is slowly happening, but we still need to integrate these ideas into our contracts and our working schedules.”

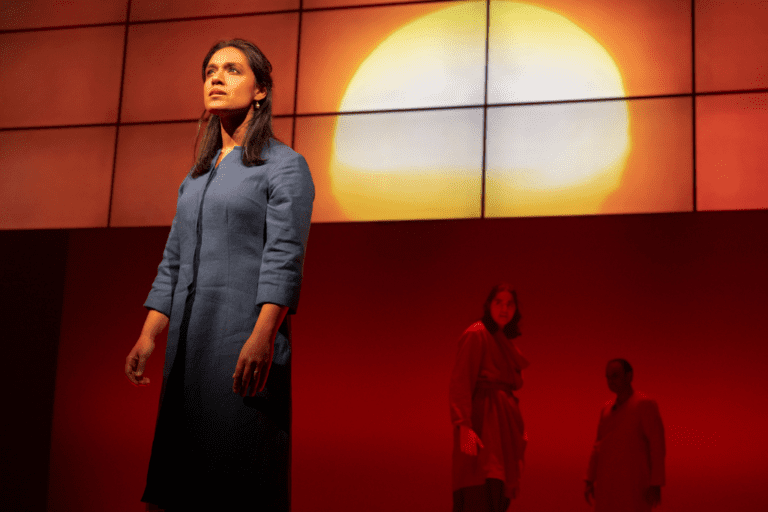

Samantha Sutherland’s dance solo slip away takes a slightly more serious approach. The show explores her relationship to Ktunaxa, a critically endangered Indigenous language with fewer than 20 native speakers left, which she began learning through online courses during the pandemic. The resulting work combines movement and text to explore themes of hope and loss. Like many artists who entered the professional world during the pandemic, Sutherland often struggles to balance between the demands of the industry and the realities of life.

As far as our sector goes, there’s this idea that how busy you are is a reflection of your values. We also tend to emphasize a person’s career over the body of work they’ve produced. There are certain things that we can do at a community level, particularly when it comes to resource sharing. But we also need to consider the fact that we operate in a scarcity environment where we’re so focused on individual shows that we often neglect the larger ecology.

“There’s often a public assumption that working in the arts isn’t a legitimate career,” she said. “I think everyone in the field deals with this to some extent. Part of it is about money and not always having enough funds to properly pay ourselves, meaning that we often have to have another job in order to survive.”

This year’s festival also features two international focus programs, part of an ongoing strategy by the organization to build relationships with artists from specific geographic regions. The first, from Taiwan, includes three projects: Meet the Bones, Three Dots, and Girl’s Notes III. The other, from South Korea, offers two shows: Festivals are Scary, Strange and Eerie (created in collaboration with local artists Emily Jung and Theresa Cutknife) and in-between space lab (created with Calgary-based Marie France Forcier and Toronto’s own Heidi Strauss).

Along with over 40 artistic offerings, SummerWorks will host a pair of info sessions with representatives from the Toronto Arts Council, the Ontario Arts Council, and the Canada Council for the Arts. Since sustainability is such a focus for so many artists, learning how to make use of the available funding systems can be a critical tool for folks at all stages of their careers, particularly when it comes to developing a work to its full potential.

“Being busy is often considered to be a reflection of your values,” Thomas said. “But if you hustle in a process, the work will often feel underdeveloped. We have a habit in Canada of taking shows to production on very tight timelines. But rest is critical to creation because it allows the work to grow on its own terms.”

SummerWorks runs until August 11. You can learn more about the festival here.

Being an Artist in the broadest sense of the word like a painter, dancer, actor, singer or comedian for example, means being never really understood by civilians.

Creativity can not be captured between 9 and 5 only, it’s a 24 hour continues cycle that runs from exuberance to deflation.

Alas, some artist do sell themselves short sometimes by proclaiming they never had a real job, because they mistakenly think that that’s a prerequisite to being acknowledged as a valuable member of society.

Being an Artist in the broadest sense of the word like a painter, dancer, actor, singer or comedian for example, means being never really understood by civilians.

Creativity can not be captured between 9 and 5 only, it’s a 24 hour continues cycle that runs from exuberance to deflation.

Alas, some artist do sell themselves short sometimes by proclaiming they never had a real job, because they mistakenly think that that’s a prerequisite to being acknowledged as a valuable member of society.