Gatekeep, gaslight, girlboss: The delight of female rage in theatre

Content warning: This essay contains mention of suicide and sexual assault.

“Wow, she is just evil,” I hear an audience member note with a chuckle at the intermission of the Stratford Festival’s Hedda Gabler. There’s a twinge of grotesque excitement in her voice: She knows Hedda is in the wrong, yet she can’t quite help but relish seeing her work her manipulative magic onstage.

Personally, I support women’s rights and women’s wrongs — especially when it comes to my girl Hedda. And it seems that at least two Ontario directors share my viewpoint, with Hedda Gabler opening twice in the same month at Stratford and at Coal Mine Theatre in Toronto. What makes her story so appealing?

To summarize Hedda’s so-called wrongs (spoilers ahead for Ibsen’s infamous tale): She burns a former classmate’s hair, destroys a scholar’s life’s work, and pretty much single-handedly drives a man to suicide, among many other questionable life choices.

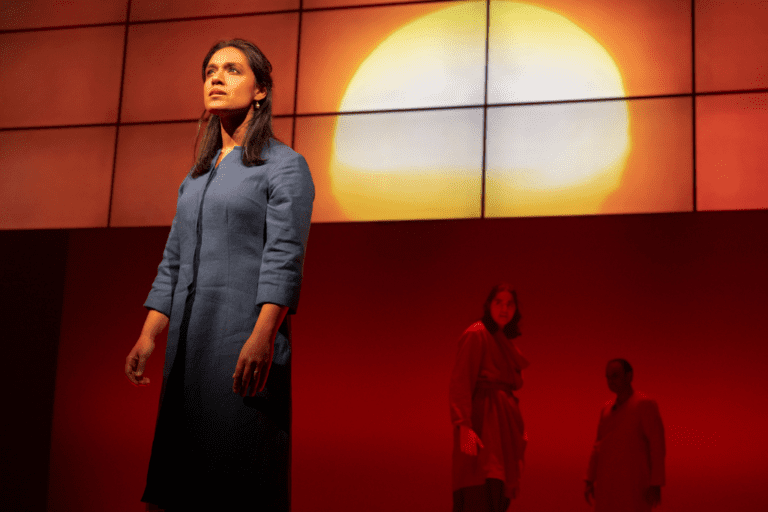

Yet, when I see these actions at Stratford under Molly Atkinson’s direction, I sympathize with Sarah Topham’s Hedda; I mourn with her, and, ultimately, I don’t want to see her fail. As she wanders aimlessly about the stage like an animal in a cage, eyes empty, heart yearning, I can’t help but hope to see her escape.

For the last couple of years, there’s been a cultural obsession with “good for her” stories, in which fictional women often commit crimes, but are nevertheless revered by fan bases. The X trilogy’s Pearl, Gone Girl’s Amy Dunne, and even Stephen King’s Carrie are idolized for their objectively reprehensible actions. (Don’t tell anyone, but I’ve been one to indulge in the occasional fan edit.)

The best thing about the tragic women in the classical canon who continue to resonate today is that they’re messy. Or at least, my favourite ones are. They’re not sanitized — they’re simply people trying to assert themselves in a society that doesn’t want them to.

So, how does this phenomenon translate to theatre? Or, more specifically, to the tragic women of today’s theatre scene?

In her director’s note for the Stratford Festival, Atkinson uses an Ibsen quote over and over again: “Find out who you are.” I must admit, I find this maxim as intriguing as she does. In the world of Hedda Gabler, where women are their husbands’ property, how the hell is Hedda supposed to figure out who she is?

Atkinson goes on in her note to describe Hedda as, “Newly married. Unhappy. Brilliant. Brave. A coward. Bored. Frustrated. Power hungry.” A contradiction upon a contradiction. Hedda as a character is incredibly astute and calculated — upon her first entrance in Act One, Ibsen says “her face and figure show refinement and distinction.” But Hedda uses all this intelligence and sophistication to inflict pain upon others. So how can we let ourselves root for her?

The best thing about the tragic women in the classical canon who continue to resonate today is that they’re messy. Or at least, my favourite ones are. They’re not sanitized — they’re simply people trying to assert themselves in a society that doesn’t want them to.

Case in point: Hedda. She’s imperfect. She acts cruelly. When Hedda is asked why she does the things she does, she answers simply: “Rage. I can’t help myself.” It’s too easy to chalk her actions up to her being an intrinsically bad person — it’s a deeper, more calculated rage. A rage for her place in society. A female rage. There’s a whole genre dedicated to it for a reason. (Taylor Swift has just copyrighted Female Rage: The Musical.)

The source of this rage in classical roles? More often than not, it’s motherhood.

Society’s expectation upon Hedda as Tesman’s wife is to give him a child. She can’t fit into this mold for a laundry list of reasons: She doesn’t want to be a mother, she has a miscarriage, and she doesn’t love Tesman. And Hedda, being as astute as she is, knows there’s no way out of these expectations. In her circumstances, it’s close to impossible that she could be afforded the power and respect she so craves. And if you’re trapped, thinking about these things over and over again: What else is there left to do but to simmer, in all-engrossing frustration, anger, and ultimately, rage?

Just a few months ago, Soulpepper’s production of A Streetcar Named Desire gave us another example of this phenomenon. Tennessee Williams’ Blanche is quite literally a pedophile, the opposite of the motherly figure she’s expected to be. She becomes trapped by her circumstance much like Hedda, and knows no other way to survive, to express her rage, but to use her sexuality to a quite self-destructive extreme. Yet, the audiences in Toronto cried, not cheered, when they saw her committed to a mental institution. Why do we root for her?

Medea, the widely known Greek tragedy but not often produced opera, was at the Canadian Opera Company earlier this year, and also resonated deeply with audiences. In a moment of trembling desire for control, Medea murders her kids in a horrendous, but decisive, exertion of power. For the whole opera, she mourns the children who have been ripped away from her; she’s left with no control over her own life, no control over whether or not she gets to be a mother. In this heinous action, she rejects the position in which she has been put. She takes control. This is quite a fresh example of female rage, from a production that stirred up a flurry of 2024 Dora Awards and general audience buzz. While the other two shows cited thus far are well-established in the classical canon, this newly resurrected opera’s success demonstrates just how hungry audiences are right now for a good for her story.

The Catch-22 of the canonical female characters is that while most of them fight tooth and nail to get what they want, the majority do not get their way. They are more often than not abused by men onstage — killed, tortured, assaulted. It’s quite puzzling how stories in which women are overpowered and ultimately lose seem to bring a seeming empowerment to contemporary theatregoers.

Here’s what I think: Today’s audiences love an angry woman onstage because they can mourn alongside her when she gets hurt because of it. The characters of Hedda, Medea, and Blanche reveal a deeper cultural desire for autonomy today. A simultaneous optimism and nihilism for the place of women in Western society. At a time when women and non-binary people in North America feel scarily on the brink of losing our reproductive rights, the rage-filled women of classical theatre who reject motherhood serve as a form of cultural catharsis.

Witnessing these women furiously oppose the expectations put on them, despite their limited rights and socially-afforded power, is empowering. Even if they’re ultimately overpowered by their stories’ conditions and ultimately their fates, their presence in each of their tragedies and their small wins reverberate through theatre walls.

Seeing Hedda get her way, even if for a moment, even if by less than moral means, is a breath of fresh air. Hedda ultimately exerts her power over her own life by ending it – a horrendously tragic end, yet in some way it can’t help but bring me a sense of twisted relief for her. And when the audience claps for the actress playing Hedda, we clap for ourselves as well. We love watching uninhibited furious women on stage because we sometimes feel like that too in our everyday lives.

Stratford’s most recent rendition of Hedda is so poignant to today’s audiences because Atkinson herself identifies with the desire to see women be unhinged onstage as a representation of ourselves: “Hedda is in all of us. Expectations, need, love, rage, boredom, fear, lust, power.”

The tragic, so-called crazy women of classical theatre are a vessel for possibility. Though they’re all trapped by circumstance, they go to every extreme to try to have their own lives, their own autonomy, and their freedom. Isn’t that what we all want? And with Crow’s gearing up for the opening of Ibsen’s Rosmersholm, another classic case of a tragic femme fatale, it certainly seems that female rage in the theatre scene is here to stay.

really love this. currently writing a monologue which explores female rage from an unlikeable character. we are complex and I’m furious regularly. I refuse to be neutered