Art Meets Environmentalism: In Conversation with Kevin Matthew Wong’s The Chemical Valley Project

At thirteen years old, Kevin Matthew Wong found himself deeply entrenched within two different worlds of purpose. According to him, he was “the kid that was really split between the drama room and the environmental club.”

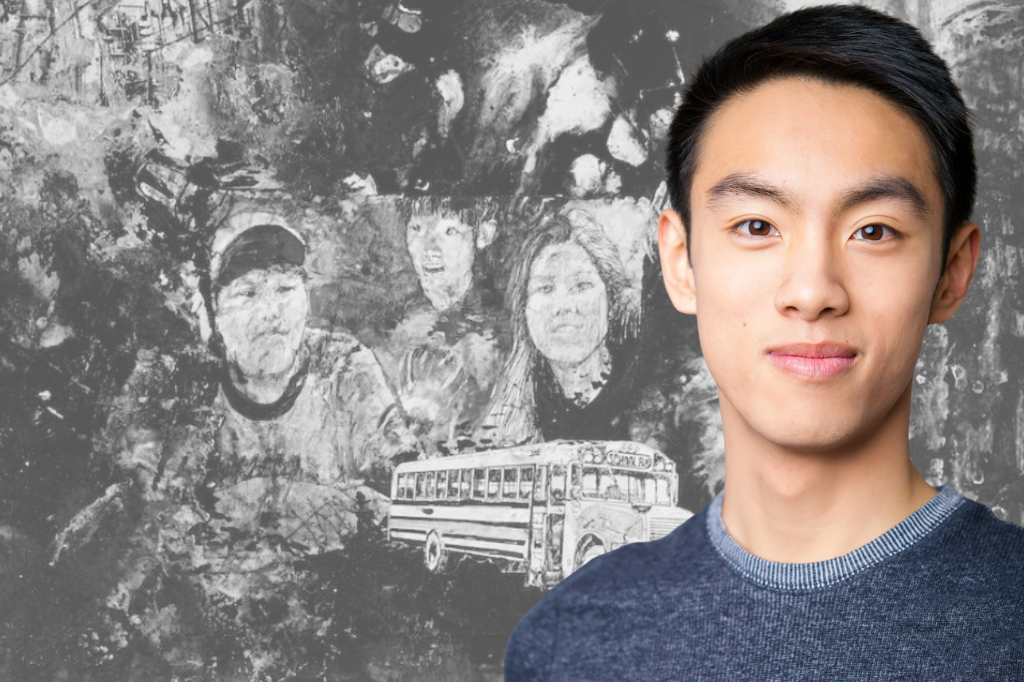

Founding Broadleaf Theatre in 2014 and co-creating The Chemical Valley Project in 2017, Kevin Matthew Wong has kept that inner kid alive, and through his artistic work is dedicated to amplifying environmental issues.

“So 50% of my days after school were trying to rehearse plays,” he recalls, “and the other 50% of my time was asking, ‘what is the voice of youth in the greatest issue of our time?,’ which is the climate crisis. There was that tension in me, always asking ‘what does this have to do with that?’ I think that really positions the origins of my company Broadleaf Theatre, where we’re able to focus on amplifying climate issues through performance.”

In our interview, Wong noted how the theatrical sphere in the GTA back in 2014 lacked an active conversation in the climate crisis. That gap became a catalyst for the creation of Broadleaf Theatre.

“It just felt like there was this lack in the theatre community I was a part of when it came to talking about these issues,” he said. “They’re impactful and important, so how can we help get that across?”

This is going on right in our backyards, and it goes shockingly unacknowledged.

Broadleaf Theatre began its creative journey with The Chemical Valley Project in 2017. Water protectors (and siblings) Vanessa and Beze Gray have dedicated their lives defending their community, the Aamjiwnaang First Nation reserve, from the Chemical Valley, one of Canada’s largest petrochemical corridors. Creators Julia Howman and Kevin Matthew Wong work in collaboration with the Gray siblings to document their activism. Through this documentation, Howman and Wong amalgamate documentary and theatrical performance to create The Chemical Valley Project, an urgent piece that Wong says he hopes will “encourage audiences to interrogate their role in Canada today.”

While the Gray siblings and their community have been rooted in the fight against the Chemical Valley for some time, the Chemical Valley first came to Wong’s attention as he was researching for another piece in development.

“I’d never heard about the Chemical Valley,” Wong admitted. “And the only reason I knew about it was because I was specifically researching to create work about climate. This is going on right in our backyards, and it goes shockingly unacknowledged.” This led Wong to an event called the Toxic Tour, where Vanessa and Beze Gray (the activists who would soon become integral to the creation of The Chemical Valley Project) act as tour guides and drive through Chemical Valley on a school bus.

“I sat on this school bus being transformed,” said Wong. “I was literally being transformed by these stories that I was hearing from Vanessa. I remember thinking, ‘there are not enough seats on this bus. Every Canadian needs to be on this bus.’ And I thought, if I’m going to take up space in this experience, then I have a responsibility to tell this story.”

I thought, if I’m going to take up space in this experience, then I have a responsibility to tell this story.

Reflecting on his own skill set as a theatre artist, Wong felt the urgency to spread the message to which the Gray siblings had dedicated their lives. “I approached Vanessa and Beze to ask if theatre might be an avenue that they might want to try as a means to amplify their message. Vanessa actually told me, ‘yeah, Beze is a lifelong theatre fan!’”

The trio had many meaningful conversations and built a great deal of trust before officially beginning the creation process. As they threw ideas around about the shape in which the piece was going to take form, they quickly realized that tackling this subject matter in a traditional performance sense didn’t quite feel right “because the issue is alive,” said Wong, “so alive for this community.”

The story they wanted to tell didn’t center around characters or performance. It centered around video and experience. “So I had some conviction that it was in the universe of documentary,” Wong explained. During the early days of creative rumination, Julia Howman became a collaborator on the project, which resulted in the show’s innovative projection design.

“We needed something portable. Something that could get up and go speak to as many Canadians as possible, not just in Toronto,” said Wong.

Both Wong and Howman, understanding the ethos of the project and their role in its journey to fruition, began the creation process diving deeper into their interviews with the Gray siblings.

“Julia and I would create based on these interviews, then we’d come together — video plus performance — and then Vanessa and Beze would come and view what we made, give their feedback on it, and then the whole process would start again,” said Wong.

The constant reformation of the work keeps it urgent and up-to-date for its current audiences.

Even when the piece is being remounted, this process happens again, allowing Vanessa and Beze to be interviewed once more, to add to the content of the piece, and to have the activists give their feedback on it before it goes up again elsewhere. This constant reformation of the work keeps it urgent and up-to-date for its current audiences.

Even in his urgency, Wong has his doubts about approaching the subject matter.

“I’m a Chinese Canadian making this work with two Anishinaabe water protectors. What right did I have to tell this story?,” he said. Wong sought guidance from Joe Osawabine and Dr. Jill Carter. He reiterated their advice: Joe Osawabine says the most powerful thing that you can do, that anybody ought to do, is talk about it truthfully from your perspective. And Carter encouraged him that he had a right to engage with the issue, and that the answer as to how should come from being very specific and honest about your relationship to this place.

Crediting the work activists like the Gray siblings have accomplished, Wong grounds The Chemical Valley Project from his own understanding and experience. “The work is based on relationship to place,” he said. “It’s based on taking direct action.”

The Chemical Valley Project keeps going because there is a team of people who believe in it. Wong and Howman acting as one means of amplification, and the Gray siblings as its nucleus. “We continue to find urgency from Vanessa and Beze saying that this piece still matters and is relevant to the work that they’re trying to accomplish. If they told us to stop, we would stop immediately.”

The Chemical Valley Project’s first performance was back in 2017, and now in 2022 the piece is heading to the Great Canadian Theatre Company in Ottawa.

“It blows my mind. I can’t believe it,” Wong admitted.

Wong ended our chat by reiterating; “our work wants to speak to the person who is on the edge of taking action. We want to push them over that edge. Let’s have our hearts in this conversation.”

Yes, let’s.

To support the Gray siblings and the Aamjiwnaang in their fight, click here and here.

For more information on The Chemical Valley Project at GCTC, click here.

Comments