‘Two Perspectives on Disability’: In Conversation with Richard Three at Shakespeare in the Ruff

Growing up as a physically disabled child in the mainstream education system, I was used to being the only disabled person in the room. I didn’t know other disabled children or adults. My whole concept of disability was about me and my own body.

The notion of being part of a disability “community” was entirely foreign to me. So when I began forging friendships with other disabled people in my early twenties, it felt like my whole worldview was turned on its head.

A similar, seismic shift in perspective is at the heart of Shakespeare in the Ruff’s Richard Three, Patricia Allison’s new adaptation of Shakespeare’s Richard III that features two disabled Richards (Alex Bulmer and Alexia Vassos) from two different universes thrust into the same orbit as they both quest for the crown.

I sat down with Bulmer and Vassos, as well as Christine Horne (who plays Everyone Else — that is, everyone from Queen Margaret to Clarence to Chorus in this three-hander adaptation) on Zoom to discuss disability as cultural identity, their relationship to Shakespeare, and the multiverse at the centre of this play.

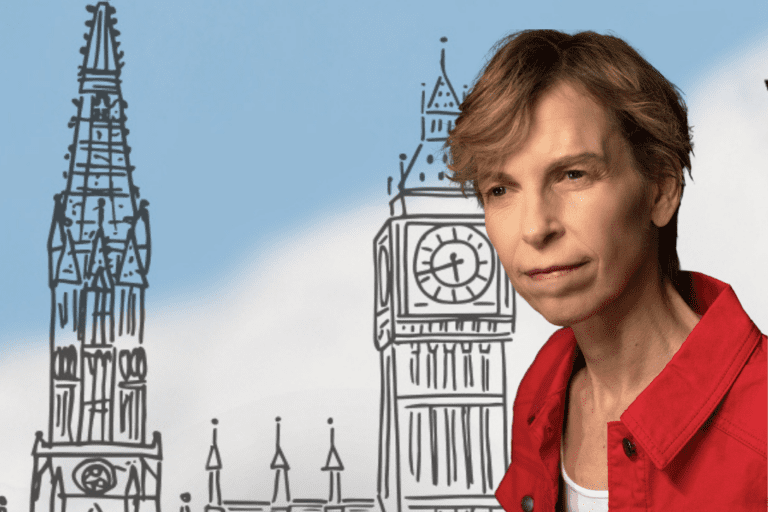

Bulmer, one of Canada’s most celebrated disabled artists who returned to Canada permanently in 2017 after a storied career in the UK, sees Richard Three as “a marker of where we are in Canadian theatre.

“There’s a need for this play,” Bulmer said, “because there’s so little work in this country that centres two disabled people at its core. And disability [in theatre] is usually seen as a solo isolated experience, while the world around you is non-disabled. In a cast of six, there’s usually one disabled person and five non-disabled people, and everyone’s trying to figure out the tragedy of the person who became disabled. So having two Richards [in this adaptation] means you have two perspectives on disability.”

Bulmer explained that the multiverse — the cosmological event that brings two Richards from two completely different universes together — allows disability to be seen as a culture, rather than a static element.

Vassos was quick to agree: “There’s an element of Richard coming in [to this world] and having his own idea of disability, and Other Richard saying ‘I have no idea what you’re talking about.’”

In the same way I had to learn as a young adult that many of my disabled friends — even those with the same disability as me — had completely different experiences than I did, Bulmer and Vassos’ Richards, too, will reckon with the vastness of disability.

It’s a kind of reckoning not often seen in productions of Richard III, which has often been used as a vehicle for non-disabled actors playing the titular character to show how well they can approximate physical signifiers of disability and shed those signifiers at curtain call. Horne, who is part of Shakespeare in the Ruff’s collective leadership team, says that this was top of mind as Allison began to craft the adaptation last year: “It was partially a reaction to so many productions of the play, even in 2022, that had non-disabled actors playing Richard.”

Productions that cast non-disabled actors as Richard often take a very surface-level look at disability: Richard is a villain because he is disabled, end of story. Richard Three will dig deeper. While Bulmer, Vassos, and Horne were all emphatic that Allison’s adaptation does not assert that Richard is not a villain (“I mean, he’s killing people!” Horne exclaimed at one point during our conversation), this production will bring more nuance to Richard’s quest for power.

“Many different societies see disability as a fixed state of brokenness,” said Bulmer. “By putting [disabled actors] in this story, we become active—and I think there’s something really exciting about that.”

In this production, if disability is active and not a fixed state, then perhaps Horne as Everyone Else is the constant around which everyone else orbits.

“I feel that my responsibility in the show is to carry the original Shakespeare story through our play, to preserve that text and those attitudes [from Richard III] for Alex and Alexia’s Richards to do their thing with or against,” Horne said.

“For me [experiencing this play], it’s a completely different experience watching Alexia be called the names Richard is called in the show than it is watching a non-disabled actor as Richard receive that,” Horne continued. “We hear the play in a completely different way. We hear the society Richard is in in a completely different way. We understand more about what a disabled person in this society is experiencing.”

This new exploration of the text will remind audiences that disabled people have always forged their own paths in response to inaccessible worlds. “You’ve tried to silence us, you’ve tried to put us into institutions, you’ve tried to kill us off, you’re still trying to kill us off,” said Vassos. “But we’ve been here, we are here, and we will be here, in every universe.”

Richard Three runs August 17 – September 3, 2023 at Withrow Park. To purchase tickets or find out more, click here.

Comments