Based On and Inspired By: How Artists Work from Real Material

Lots of plays that grace our stages are complete fictional accounts. But many others are based on an element of reality, either a place in time, a historical figure, or a monumental event. What is it like to create, act in, or design a show that is tied to reality? We spoke to playwright Marie Beath Badian, actor Andrew Chown, designer Camellia Koo, and theatre creators/performers Kim Collier and Daniel Brooks about what the experience has been like for them.

MARIE BEATH BADIAN, Playwright, Prairie Nurse

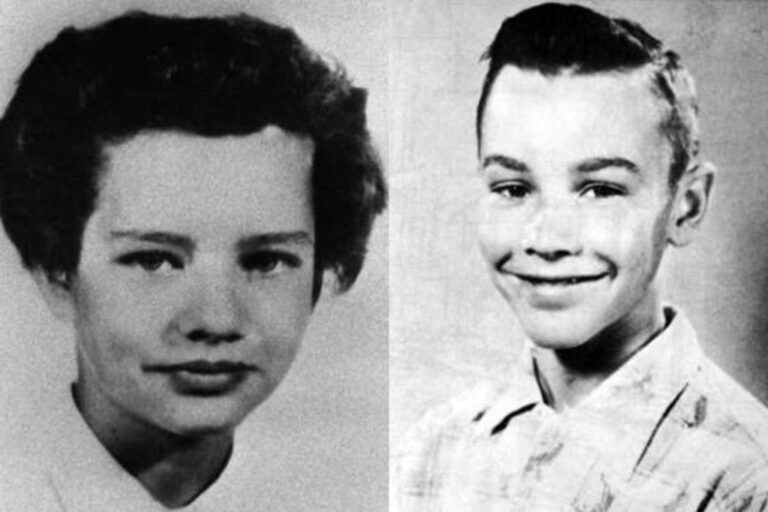

Everything playwright Marie Beath Badian writes is inspired by something real. “I don’t have the capacity for science fiction,” she says. In 2005, she was commissioned by the Blyth Festival to write a play. Her mom had moved from rural Philippines to rural Saskatchewan to work as a nurse in the 1960s, and she thought there might be a story in that. So forty years later, she and her mother travelled back to Arborfield, Saskatchewan to find the heart of the narrative.

Badian had written letters to the editors of several community newspapers, asking for anyone who remembered her mother to get in touch. She heard from a wide variety of people, including her mother’s head nurse, the man who cleared the skating rink during the winter, and a candy striper at the hospital where her mother worked. Many were in their eighties or nineties.

During their time in Arborfield, “every single person would look at [my mother] and immediately say, ‘Where’s the other one?’” Badian remembers. “Always. Always always always.” The “other one” was Penny, the other Filipino nurse who worked at the same hospital. “The stereotype of not being able to tell Asians apart was just so vivid, but in such an innocent and kind [way],” she says. It was a “curious inquiry that they were asking.” That experience became the basis of Prairie Nurse’s mistaken-identity plot.

Cast of Prairie Nurse at Factory (2018). Photo by Joseph Michael

The real Penny is now dead, but her daughters—one who lives in Saskatchewan, the other who lives in Montreal—have read Prairie Nurse and are coming to Toronto to see the play at Factory Theatre, which is on now. “They support [the show] inspired by their mom, so that’s a big deal to me,” Badian says.

Before their trip, Badian’s mother told some stories about that time in her life. But “they were bullet points,” Badian said. “They were very removed.” Once they arrived in Saskatchewan, though, “the story started to just pour out of her… she was completely transformed. Everything was so vivid.” The play that eventually became Prairie Nurse couldn’t have happened without the Saskatchewan trip, Badian says: “In terms of my research, that storytelling could only happen because I was there.”

Cast of Prairie Nurse at Factory (2018). Photo by Joseph Michael

ANDREW CHOWN, Actor, Vimy

Last summer, Andrew Chown appeared in Vern Thiessen’s Vimy, at Soulpepper. The story was loosely inspired by the life of World War I nurse Clare Gass, a woman from the small town of Shubenacadie, Nova Scotia. Chown played her fictional boyfriend, Laurie, who grew up in Stewiacke, a village close by.

Last summer, Andrew Chown appeared in Vern Thiessen’s Vimy, at Soulpepper. The story was loosely inspired by the life of World War I nurse Clare Gass, a woman from the small town of Shubenacadie, Nova Scotia. Chown played her fictional boyfriend, Laurie, who grew up in Stewiacke, a village close by.

“There were two things about the play that were important to me: knowledge about Vimy and the war, and knowledge about what it was to be an East Coast boy,” says Chown. He figured he could learn about the war through books and film. Travelling to France wasn’t an option, but the East Coast was a much more accessible source of research. So Chown took a road trip down to central Nova Scotia.

Driving into Shubenacadie, Chown had no plans—no one lined up to speak to, no specific location to stop at. Google Maps told him there was a tinsmith museum in town, so he decided to make his way there first, hoping to uncover something about the Gass family. It being late April and offseason, the museum was closed, but Chown was determined. “I thought, Someone must have the keys,’” he says. So he went across the street to the hardware store, and when he explained his reason for being in the area, the man working made a call. Marilyn, the woman who held the museum keys, couldn’t be reached, but the chance stop at the store wasn’t without value: Chown was told Gass’s childhood home was down the road.

Andrew Chown in front of Clare Gass’s childhood home.

Giddy, Chown got back in his car and drove to the house, which is now a retirement home, and peeked his head inside. He met a man, Donald, whose mom used to play chess with Gass growing up. They spoke for an hour, and near the end Donald offered to call Marilyn, who he knew as well. She still couldn’t be reached, so Donald gave Chown vague directions to where she lived: “Down the road, make a right, keep going—it’s next to the one with a pile of tires out front.” He also pointed Chown in the direction of the graveyard where he thought Gass may be buried.

Chown found the graveyard and stopped for a quiet moment in front of the family plot before making his way to Marilyn’s house. As he walked down the path, ready to explain his trip for the third time of the day, the screen door swung open. “I hear you’ve been looking for me!” she beamed. Marilyn took him to the museum, unlocking it for a private tour, where he saw WWI memorabilia and discovered a Gass family history memoir.

Christine Horne and Andrew Chown in Vimy at Soulpepper (2017). Photo by Cylla von Tiedemann

Chown says that hearing stories firsthand by the people who grew up in the area, about everyday life and the effect the war had on the neighbouring towns, made the stories in Vimy more real to him. “Seeing the care they had for their own history made me want to do right by their memory, and the memory of the people who died,” he explains. “It’s one thing to read the play and imagine what could be; it’s another to talk to somebody who knew Clare, or to stand at her grave.”

Chown says that, as an actor, he’s often trying to imagine a character’s past, their history. “The trip made me feel rooted to the place in a tangible way. And that definitely affected my acting. Internally, it gave me confidence. And that’s half the battle.”

Andrew Chown at Clare Gass’s graveyard.

CAMELLIA KOO, Designer, carried away on the crest of a wave and East of Berlin

Camellia Koo has designed sets for a number of plays based, in some way, in reality, including David Yee’s carried away on the crest of the wave, centred around the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami (Tarragon 2013, NAC 2018), and Hannah Moscovitch’s East of Berlin, a post-Holocaust story (Tarragon and national tour 2007–08).

On every such project, Koo does a ton of research about the history of the event, the time period, or the lives of the real people involved: she collects images, reads books and online material, consults experts. But while research can help inform her designs, it will never be what her design choices are based on. “You can’t get too caught up in it,” she says. “[The play isn’t] about that stuff, it’s not about the historical details. It’s important to design the story correctly first.”

carried away on the crest of a wave at Tarragon (2013). Photo courtesy of Camellia Koo

Any time Koo works on a historical show, she always tries to look for a second layer, something she can tell about the story beyond the obvious. “You always want to be truthful about the history, to honour it, but you want to honour something deeper than that,” she explains. With the first production of carried away, at Tarragon Theatre in 2013, the set was made out of plastic that had a gel on it, obscuring a surface that would otherwise have been transparent. When people stood behind it they couldn’t be seen clearly, a visual representation of the way the tsunami affected everybody’s lives. (The recent National Arts Centre production had a different aesthetic altogether.)

In East of Berlin, the set was a bookshelf, not only filled with books but also with artefacts. Koo had done a lot of research around the specific generation of the characters, and some of the artefacts matched the time period. But there were also historical things that wouldn’t normally be found on a shelf: a pile of babies’ shoes, a heap of glasses, a jar of teeth. Iconic images from Holocaust.

“If we had been too caught up in historical accuracy,” says Koo,“we wouldn’t have come to those ideas.”

East of Berlin at Tarragon (2007). Photo courtesy of Camellia Koo

KIM COLLIER AND DANIEL BROOKS, Theatre Creators and Performers, 40 Days and 40 Nights

The event that inspired Kim Collier and Daniel Brooks’s 40 Days and 40 Nights, on now at the Theatre Centre, was one they took upon themselves to experience: a trip to India, where they were dedicated to making every choice based in love.

“The question we carried to India was based on a question I was carrying in my life and wanted to think more about,” says Collier. “‘How can we love better?’ It’s such a struggle in our relationships, in our transactions in life. I was wondering if it was possible to make a public ritual in which we consider that and in some way nourish ourselves to be a little bit more loving.”

The pair ended up spending a lot of time in temples, out in nature, and communing with different religions, from Hindus to Buddhists, Jains to Sikhs. They asked locals questions about their expectations around love and marriage, and asked those same questions of themselves. They read Plato’s Symposium and Hafiz poetry, studied the history of Eastern philosophy. Brooks took up Vipassana meditation, which is based in some fundamental idea of love. They were “swimming around out there, in the dark, trying to learn,” as Collier puts it.

Rehearsal shot of Kim Collier and Daniel Brooks in 40 Days and 40 Nights. Photo by Dahlia Katz

Prior to leaving for India, they didn’t know what shape their public presentation would take, or that it would revolve around ritual. While Brooks says he’s someone who is happy to ponder and meditate—“I would have done a slideshow”—Collier always had a piece of theatre in mind.

“I was definitely paying close attention to the various rituals and symbols and smokes and flames while I was there,” she says, “writing those things down in the consciousness that they might inspire a presentation.”

When they returned home, Brooks came across a book called In Praise of Love by French philosopher Alain Badiou. A “passionate treatise in defense of love,” the text offers a “new narrative of love in the face of twenty-first-century modernity.” Compelled by the ideas in the book, Brooks and Collier used it in their process of turning their travel experience into a presentation.

“I started to do some writing and, over the months, Kim’s response was not very encouraging,” says Brooks. Collier wasn’t interested in the internal conflict and confusion Brooks wanted to write about. “Slowly,” he adds, “I began to shed that and tried to imagine a different way of approaching the subject than I’m usually accustomed to.”

Kim Collier and Daniel Brooks in 40 Days and 40 Nights. Rehearsal photo by Dahlia Katz

40 Days and 40 Nights, coproduced by Necessary Angel Theatre Company, Electric Company Theatre, and the Theatre Centre, is not a re-creation of their experience in India, nor is it actually based on real-life events. Rather, they used moments from their travels that moved them—like the publicness of religious rituals, and being invited to participate in them—along with meditations and readings around the idea and the word “love,” to create their own public ritual.

It is unlike any theatre either of them have done before; it’s more of an experience, a happening. “I don’t think there’s anything unusual about it,” finishes Brooks. “We were just responding to a very particular process.”

Prairie Nurse is on at Factory Theatre until May 13. For tickets or more information, click here.

40 Days and 40 Nights is on at the Theatre Centre until May 6. For tickets or more information, click here.

Comments