Mad Kitchen: Owais Lightwala’s Haleem

In “Mad Kitchen,” Madeleine Brown speaks to members of the Toronto theatre community about one of their favourite recipes.

Why Not Theatre’s managing director, Owais Lightwala, uses food as a metaphor to describe his desire to produce theatre as opposed to create it: “I’m more interested in the serving of things than the making. My role isn’t to have the recipes, or to be the chef. My role is to take care of the chef.”

Lightwala was born in Pakistan, spent his childhood in Dubai, and arrived in Canada at age fourteen. He grew up eating haleem, a slow-cooked stew of meat and wheat traditionally prepared in large quantities. To this day, he always enjoys it best when eaten communally either with his immediate family or at his mosque on the day of Ashura as part of the Shia Islamic calendar.

A volunteer food server at his mosque, Lightwala says “there is something simply beautiful about the serving of haleem when we are literally feeding our community.”

Given the dish’s intrinsic connection to community, it was an obvious choice for Lightwala’s first Community Meal at the Theatre Centre in December 2015: a tribute to the longstanding support the organization provided Why Not during its initial years. (Up until last September, the company still worked from the Theatre Centre Cafe, until they “literally ran out of space at the tables.”) A full morning of cooking and one broken hand-blender later, Lightwala, with Community Meal founder Remington North as his sous chef, quickly sold out the lunch.

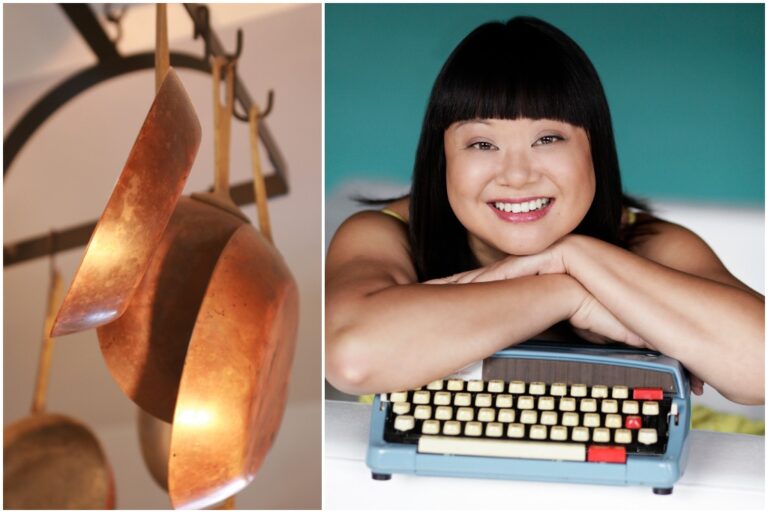

Remington North and Owais Lightwala in the kitchen

Food serves as an entry point and community builder in several Why Not productions. In A Brimful of Asha, Asha Jain serves her audience samosas, and, in the case of the 2017 New York City production, chai. “It’s integral to the success of the show,” says Lightwala. “It allows her, a non-performer, South Asian immigrant, to host you in a way that changes the relationship of audience and performer.”

Meanwhile, Like Mother, Like Daughter, which was inspired by Asha, is set around a dining table and concludes each performance with a meal, allowing audience members to engage with the performers—actual pairs of mothers and daughters. “In some ways,” says Lightwala, “we like to say that is the show, the conversation after the show.”

It is impossible to discuss haleem, Lightwala’s passion for community, or even his career in theatre without mention of his own mother. He credits her as the inspiration for everything he does now. “She would probably be very disappointed if she heard that because she would go, ‘Oh, I was working on making you a doctor. If I’d known this was all my fault, I wouldn’t have tried so hard.’”

Every time Lightwala prepares haleem, it warrants a phone call to his mother to confirm its preparation. Despite familiarity with the recipe, he takes pleasure in acknowledging her authority on the subject. In fact, Lightwala somewhat seriously proposes we print her phone number in place of the actual recipe for the most authentic preparation experience. (Sadly, Intermission and I took the boring, less interactive route.)

Owais Lightwala’s Haleem

Note: According to Lightwala, Shan Haleem Mix and ginger-garlic paste are available at South Asian grocery stores and “in the ‘ethnic’ food aisle of white-people grocery stores like Loblaws and No Frills.” He says any brand is suitable as long as the box features the words “haleem mix.”

Ingredients

- 1 box Shan Haleem Mix (including spice and grain packets)

- 1/2 cup + 2 tbsp vegetable oil or ghee (i.e. clarified butter), separated

- 1 heaping tbsp ginger-garlic paste

- 1½ lbs mutton (Lightwala’s preference) or chicken, cut into pieces

- 15 cups water

- 1 large or 2 medium onion(s)

- cilantro, fried onion, ginger (thinly sliced), green chilis, and/or lemon or lime wedges, to garnish

Method

- In a large pot or pressure cooker, heat ½ cup of oil or ghee over medium-high heat. Add 1/2 to 2/3 of the haleem mix spice packet depending on your tolerance for spice. (“It’ll be spicy!” warns Lightwala.) Then add the ginger-garlic paste and meat, and stir to combine.

- Pour in the water and bring to a boil over high heat. Once boiling, cover the pot with a lid, lower the heat, and simmer for at least an hour and a half (or upwards of three, depending on the meat), stirring occasionally to prevent sticking. The cooking is complete when the meat is fall-off-the-bone tender upon touch. Taste for seasoning. Note: If you are using a pressure cooker, allow for two or even three whistles. Don’t overfill your pressure cooker (i.e. no more than two-thirds full), but make sure there is enough water to completely submerge the meat.

- While the meat is cooking, add the remaining 2 tablespoons of oil or ghee to a separate frying pan over low heat. Thinly slice the onion and cook it in the pan for approximately twenty minutes, stirring occasionally to start and more frequently towards the end to prevent burning. Once they’re browned, turn off the heat. (“I like to burn them ever so slightly and make ’em crispy,” shares Lightwala.) Set aside some of the fried onions should you desire them as a garnish.

- When the meat is done, remove it from the pot or pressure cooker—keeping the broth—and shred it using your hands or two forks. Then add the meat back into the broth along with the contents of the haleem mix grains packet. Stir continuously to avoid clumps. After 20 to 30 minutes, add the caramelized onions and remove from heat. If it looks too thick, add an additional cup of water. No matter what: always keep stirring.

- Serve the haleem with your choice of garnishes. For bonus points, heat up additional ghee and top individual servings with a spoonful, adding the leftover fried onions and cilantro while it’s still hot for an awesome sizzle (and taste!).

Comments