REVIEW: Bengal Tiger at the Baghdad Zoo at Crow’s/Modern Times Stage Company

Well, yes, there’s a large cat, and yes, there’s a zoo more or less situated in Iraq.

But what happens in Rajiv Joseph’s Pulitzer-nominated Bengal Tiger at the Baghdad Zoo is more complicated than a quippy title can encapsulate. The tiger may or may not be an approximation of God; the cages of the zoo might be mental illness or violence or any number of things. Produced jointly by Crow’s Theatre and Modern Times Stage Company, this Bengal Tiger is intimate and in-the-round, not unlike last month’s stunning Uncle Vanya. But this is an intense and troubling play, a story of war and the ghosts it creates — and it’s also a fascinating case study of multilingual drama on a major Canadian stage.

Director Rouvan Silogix’s take on Joseph’s text is understated and sparse — and it emphasizes the play’s trove of mysterious ambiguities. When we meet the tiger, played here by a spitfire Kristen Thomson, we know immediately, from the tiger’s sardonic commentary, that this is a world of in-between: in between human and animal, in between violence and peace, in between east and west. Soon the tiger encounters Kev (Christopher Allen) and Tom (Andrew Chown), and the human drama becomes clear — it’s the Iraq war, and these American marines are woefully ill-equipped with the life skills necessary for battle, let alone re-entry into the US. A translator, Musa (a delightful Ahmed Moneka) is the soldiers’ last hope for connecting with the Iraqi people and their culture — but he has phantoms of his own, in the form of Ali Kazmi’s Iraqi Man/Uday, characters overflowing with villainous smarm. Musa and Uday (son of Saddam Hussein, we find out) have a tangled history, and much of the play follows Musa as he reconciles his translating work with this traumatic backstory.

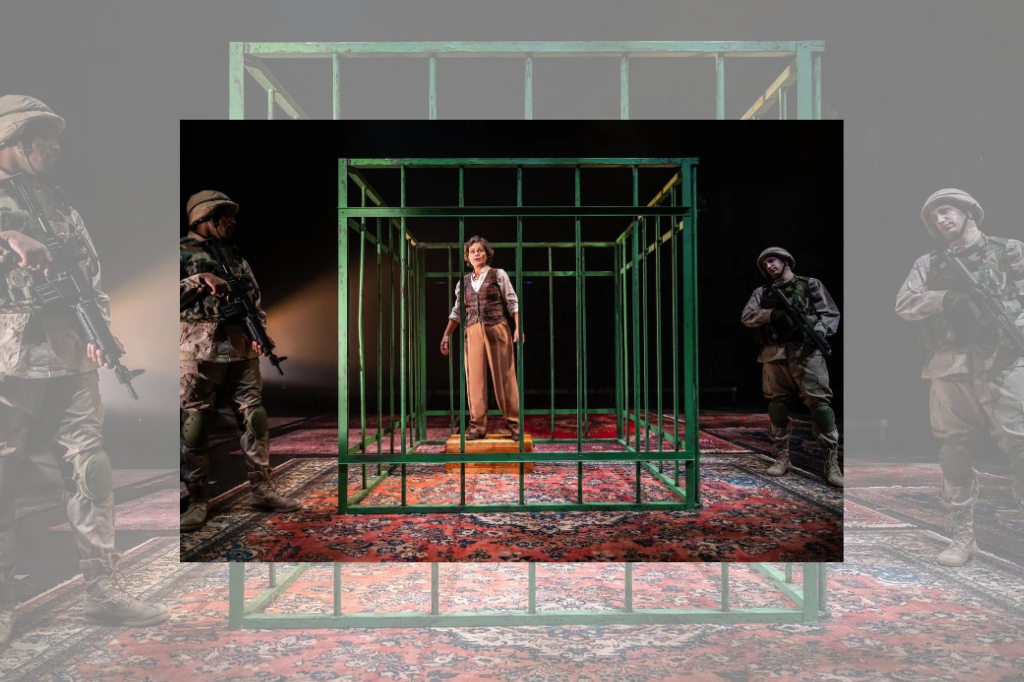

People die, limbs sever, time passes. Joseph’s play is never not intriguing — at times the Pulitzer nod feels richly earned, and with zippy pacing Silogix’s direction amplifies the text’s irreverence and verve. But some elements interfere with Silogix’s vision. Emotional scenes often fall victim to feeling overly shouty; sightlines occasionally falter within the tricky in-the-round staging. Lighting sometimes feels underexplored, and topiary animals suspended from the ceiling do not match their orated descriptions — “look there, a giraffe!,” we hear, yet in the giraffe’s place is… something else. It’s a small discrepancy but a distracting one, at odds with much of the rest of the props’ rather literal aesthetic, and the story here is so nuanced and complex that those lost moments matter. The rest of Lorenzo Savoini’s set and props are stylish and effective — the tiger’s cage, the golden toilet seat and gun — as are Ming Wong’s costumes (especially for the decidedly unfeline tiger, clothed in a waistcoat and trousers with not a stripe in sight).

Quibbles subside when action unfolds purely in Arabic without translation or context — the struggle of the monolingual soldiers immediately becomes clearer, as does Musa’s crucial role in the war. Silogix has deftly handled the play’s multilingualism, and the emergence of a culture somewhere between the soldiers’ and the translator’s is simple and elegant: high-stakes translations propel the play forward, saving lives and quelling tempers. As the play progresses and we get to know Musa a little better, the role of language in his life becomes clearer, and sadder, and more dangerous. The life of a combat translator is always perilous — and that effect’s realized gorgeously here, in a theatre where one can safely assume a percentage of the audience won’t speak Arabic.

Bengal Tiger at the Baghdad Zoo critiques the Iraq war with a hearty dose of fatalistic humour and linguistic allure. For the most part, this production takes its missteps in stride. There’s humour, there’s tension, there’s heartache. Plus, Thomson’s a hoot as our stripeless tiger — it’s worth a visit to Crow’s for this seldom-performed oddity of an important script.

Bengal Tiger at the Baghdad Zoo runs at Crow’s October 11 through November 6, 2022.

Comments