REVIEW: dance: made in canada

Any avid Intermission reader will be very familiar with reading about performance “made in Canada.” It’s pretty great, right? But what makes theatre, dance, and other performances unequivocally Canadian? The answer can feel both broad and quick-shifting, just like the population and politics of Canada itself.

The biennial “dance: made in canada / fait au canada” festival supports Canada as a hub for dance creation by being “a platform for emerging, mid and established dance artists to share their visions and voices.” The festival, which played at the Betty Oliphant Theatre in mid-August, offered a variety of dance programming, including dance film screenings, workshops, a podcast called “The ‘D’ Word,” and informal artist chats. A particularly unique series called “What You See Is What You Get” places pieces by emerging choreographers into a lottery right before the show starts; what’s performed is totally up to chance.

Importantly, this year’s festival showcased dance’s distinctive nature in this country through its dedication to Danny Grossman. A boundary-pushing central figure in Toronto’s dance community, Grossman passed away on July 29 of this year as he was curating the festival’s front-of-house exhibition in his honor. Walking through this retrospective between programs, you can feel Grossman’s great importance to his network of dancers at York University, his touring company, and beyond.

For the festival’s Mainstage series, founder Yvonne Ng brought in National Ballet of Canada choreographic associate Robert Binet and Kaha:wi Dance Theatre founder Santee Smith/Tekaronhiáhkhwa to each curate hour-long programs featuring choreography created and performed by dancers from across Canada. I had the opportunity to see the Morrison Mainstage Series (curated by Ng in memory of lighting designer David Morrison) and the Binet Mainstage Series, and was sorry to miss Smith’s program.

True to the festival’s purpose, Ng’s Morrison Series is an exemplary showcase of the ways in which Canadian artists are innovating dance as concurrent means of storytelling and aesthetic expression. The first piece is an excerpt from You Touch Me, performed and choreographed by Vancouver-based artists Emmaleena Fredriksson and Arash Khakpour. From the moment the two hit the stage, You Touch Me proves both infectiously charming and subtly provocative. Central to this work are Khakpour and Fredriksson’s reckonings with their Canadian identities, both having been born and raised abroad. They explore this tension by blurring the boundaries between movement and text so well that the two no longer feel mutually exclusive. They use contact improvisation as a game to see who can cup the other’s eyeball first, or explain a dance combination to each other only using their mother tongues.

The piece is rich with moments that feel simultaneously hilarious and innovative: using different multilingual covers of Drake’s “Hotline Bling” as transition music between sections was unexpectedly delightful. Each of the pair’s choices feel unserious yet intentional while being incredibly engaging throughout.

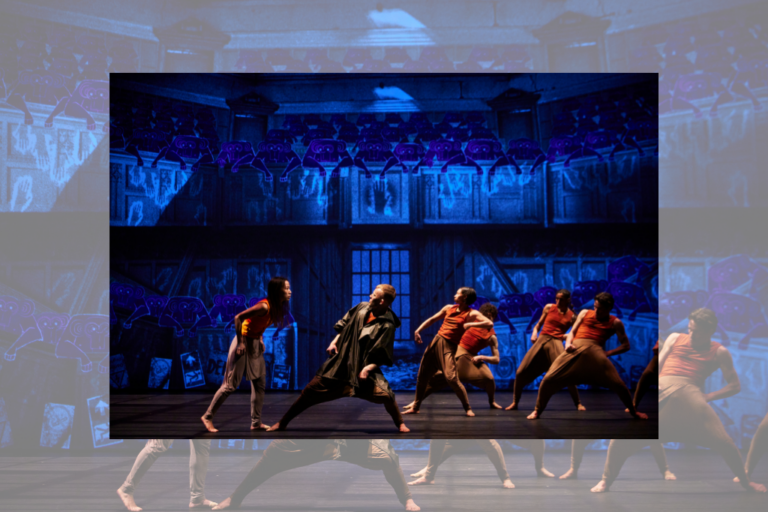

While You Touch Me interrogates the increasingly global nature of Canadian identity, the Morrison Series also presents L’ENCRE NOIR (translatable to “Black Ink”), a very different but equally exciting work that epitomizes the distinct aesthetic of contemporary dance in Montréal. Choreographed and performed by Montréal artists LA TRESSE (Geneviève Boulet, Erin O’Loughlin, and Laura Toma), the piece’s program notes that it “draws upon the Romanian, Québécois, and Irish roots” of each artist. The result is a visceral yet aesthetically striking exploration of early European rituals, with clear allegories to both pagan and theistic motifs (curated by set designers Marilène Bastien and Alexanda Levasseur, and lighting designer Hugo Dalphond). A revolving runic symbol lights up in the back corner of the stage, while the dancers are costumed in the likes of red nun habits and Puritanical grey skirts and blazers.

These bold curatorial choices perfectly complement compelling choreography and performance. Toma begins the piece rolling through her spine and shoulders walking towards the front of the stage, harshly whispering in a foreign tongue. Donning a form-fitting magenta unitard, Boulet only uses her back to move herself from one side of the stage to another. Uncanny yet evocative, the piece represents an unwavering commitment to a shared aesthetic vision on all fronts. Both pieces in the Morrison Series are excerpts of longer works, and I hope these artists have the opportunity to perform them in full in Toronto soon.

As a festival that advances new work by project-based artists, it’s important to me to emphasize the great success of the choreography presented in the Morrison Series. The Binet Series includes works entirely by Toronto choreographers (Jasad Dance Projects / Meryem Alaoui, Derek Souvannong, Vania Dodoo-Beals, and Human Body Expression / Hanna Kiel). These pieces included fantastically skilled dancers, with choreography emphasizing dance as a medium for interpreting musical accompaniment. I hope that in their future endeavors, these artists use choreography to construct dancework of a deeper narrative, cultural, or aesthetic meaning, alongside great musicial collaboration.

At the end of each series, audiences have the chance to cast a ballot for their favourite piece of the night for an award bestowed later. At least for the Morrison Series, I’m still conflicted about my choice. When it comes to dance made in Canada, there’s an overabundance of great work happening.

dance: made in canada closed on August 20. You can learn more here.

Intermission reviews are independent and unrelated to Intermission’s partnered content. Learn more about Intermission’s partnership model here.

Comments