REVIEW: Fifteen Dogs at Crow’s Theatre

The show may be at Crow’s Theatre, but there’s a new animal on stage…and it’s a top dog.

With a compelling plot, simple yet fanciful design, and a dose of puppy philosophy, Marie Farsi’s sharp, snappy adaptation of André Alexis’ Giller-winning novel Fifteen Dogs is a pawesome time at the theatre that barks up the right tree.

Wandering through the streets of Toronto, gods Hermes and Apollo (Mirabella Sundar Singh and Tyrone Savage, a highly entertaining double act) make a bet about the nature of human intelligence, debating whether self-awareness is merely a catalyst for pain. If another creature were gifted the ability to think like a person, Apollo argues, that creature would live a worse life for it, dying miserably. The wager concerns a group of fifteen dogs staying at a vet’s office overnight, who are given, so to speak, a new leash on life. The escaping dogs build (and topple) a new social order, and the gods watch curiously as each meets its inevitable end.

As a metaphor for our own existence, Alexis’ work shows us two faces of human intelligence. One face adds a certain malevolent canniness on top of the baser instincts of insular suspicion and violence, as the dogs divide into factions: Achilles the Neapolitan Mastiff (also Savage) and his supporters, afraid of changing too much, scheme to eliminate those who glory in this new mental expansion. The other sees the beauty of the world in a way that invites wonder and creates art. Both types of beings are challenged by the day-to-day necessities of survival, as well as the derision of others who do not understand them.

One of the most interesting concepts here is the pitting of nature against nurture — new potential against entrenched frame of reference. The dogs have been shaped by their former lives and different perceptions; even the evolution of their language shows that human intelligence does not equal human-like opinions, but indicates that certain feelings and themes become universally important in higher-level thinking.

For example, Majnoun the black poodle (Tom Rooney) and his human friend Nira (movingly played by Laura Condlln, as the one human to fully understand a dog) have a discussion about love versus the delight of casual sex from a “bitch in heat.” Nira finds Majnoun’s views socially distasteful, but eventually admits to the logic in finding pleasure where everyone consents. At the same time, Majnoun begins to understand more and more what the elusive concept of human love means – and in the park, Achilles wonders with some discomfort why he suddenly wants to be around his doggy paramour Rosie (also Condlln) all the time, not just for breeding.

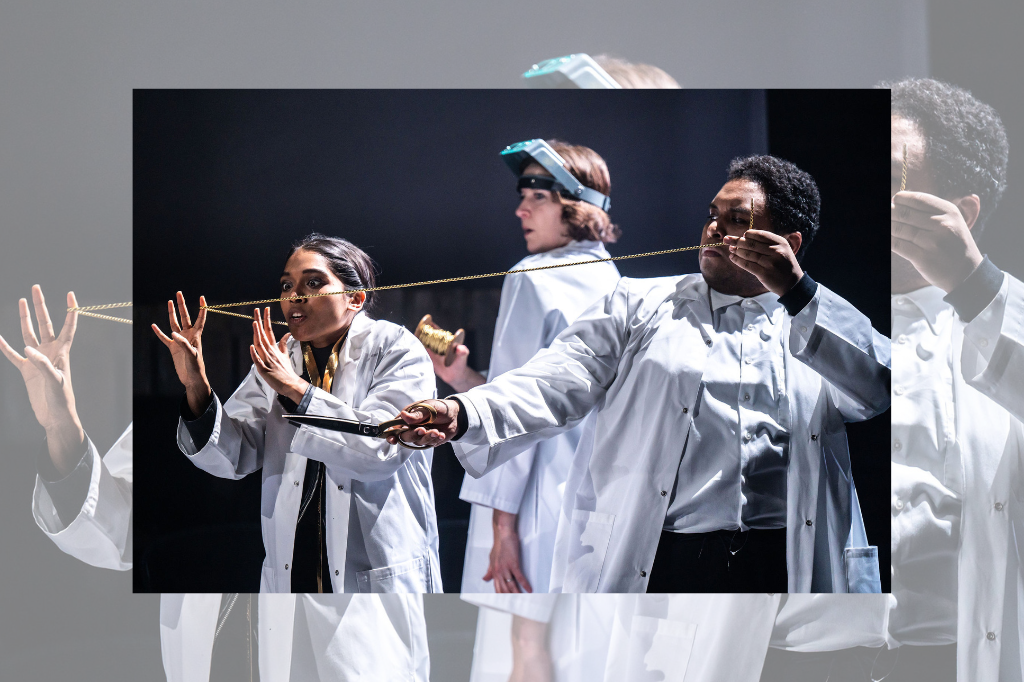

In that vein, the production has the fascinating task of creating a world and characters that are trapped between human and canine; we’re in luck that both the show’s design and cast doggedly (and successfully) pursue that vision. Set, props, and costume designer Julie Fox’s stage is quite simple, suggesting High Park with a few stray rocks in the centre, and the audience in the round. We’re given a slightly skewed sense of proportion by the (understandably) human-sized dogs, as well as the two utility poles and fences that frame the stage. These set pieces suggest the foreign human world of order and ownership that encroaches on the dogs’ wild space.

Fox also uses small models as fun details to further give the audience a sense of scope. On one rock, we see a model of each dog so that we can envision them writ large in the actors; the dwindling number of models increases the narrative tension as the play progresses. In another moment, a TTC driver pulls a tiny streetcar across the stage, which on opening night earned a laugh of recognition.

Instead of attempting to turn the actors into dogs with makeup, à la the stage production of Cats (or, far worse, the CGI movie version of Cats), they wear fetching human fashion to effectively suggest appearance and personality. A soft, cowl-like grey scarf forms the “cascading jowls” of Achilles. Prince the poet is a 70s rockstar, with wild hair, glasses, and a groovy ensemble of brown and gold. Majnoun the black poodle wears the all-black ensemble of a high school drama teacher, and Benjy the beagle looks like the bumbling half of a silent film duo with his trilby hat and checked jacket.

All this would be “fur” naught if the actors displayed even a shred of self-consciousness. Instead, we’re treated to a compelling mixture of sagacity and self-scratching, dignity and defecation, the latter embodying the reckless abandon of creatures unused to human social mores. Stephen Jackman-Torkoff is a crackling burst of energy as both Prince and Zeus; swaggering and tumbling in ecstasy over his latest creation, he howls the body electric. Peter Fernandes’ Benjy is a delight as he sweats and performs for attention, a little dog trying to take up a bigger and bigger space. Even dogs with smaller roles each get a moment in the sun, clearly differentiated in physicality.

The ultimutt canine impersonator, though, is Rooney as Majnoun. Regal and deliberate in every movement, staring with meaning and purpose, he’s the most “human” of the dogs. Such is his commitment, however, that ironically, he sometimes makes you forget the human behind the dog. The show’s peak of physical comedy may be when, attempting to find a comfortable place to sit on a cushion, he rotates his body around and around with agonizing, familiar deliberateness.

It would be wrong, though, to bill the show purely as a comedy; it impressively mixes its absurd conceit with the horrors of hatred, abuse, and murder, and the deep grief of abandonment, betrayal, and loyalty that has nowhere to go. (Let’s just say that anyone who’s cried over Futurama’s classic “Jurassic Bark” episode may want to bring a pack of tissues.)

Fifteen Dogs is a sprawling piece of theatre, at almost three hours, and, impressively, it’s capable of holding our attention for almost the entire time. However, the second half slows down the story, showing a few cracks in its pacing. Sometimes we go a bit too long without catching up with specific dogs in an effort to preserve our ignorance of their fate, which has the unfortunate effect of lessening our interest in that fate. More of an issue is that Majnoun’s growing friendship with the human Nira is really the heart of the show, and its ending causes a deflation in emotional energy that the otherwise beautiful ending does not entirely regain.

The production of Fifteen Dogs is the first recipient of Crow’s Theatre’s Canadian Literature Adaptation Fund, and already makes a great argument for the program in its exploration of dogs versus gods. The dog run has been extended to February 12th, which is a good thing; it’s an impressive achievement that deserves to be seen by as many humans as possible. In fact, as a decided cat person, I’ll even forgive the vicious cat slander it contains (to be fair, it’s pretty funny). Hound your friends to go.

Fifteen Dogs runs at Crow’s Theatre January 10 through February 12, 2023.

Comments