REVIEW: Led by Guillaume Côté and Robert Lepage, this balletic Hamlet re-invents a classic

To dance, or not to dance — is that the question?

It’s a thrilling offering from Guillaume Côté and Robert Lepage: a wordless Hamlet, beautifully led by Côté as the Prince of Denmark and staged by Lepage with gravitas and wit. Playing in Toronto for a week-long limited engagement presented by Show One Productions and produced by Ex Machina, Côté Danse, and Dvoretsky Prodctions, this stylized Hamlet is packed with intrigue, an intermission-less, 100-minute sprint through the motions of Shakespeare’s tragedy. For the most part, it’s successful for a first outing: gripping dance sequences and inspired casting breathe new life into the tale, easily replacing those ever-so-famous words with gestures. Ophelia’s suicide, Hamlet’s soliloquy, the final duel — together, Côté and Lepage make those canonical moments feel new.

Staged in the Elgin Theatre, this Hamlet draws its first breath through projected surtitles that hang over the playing space. These surtitles are more than just functional — they comment as well as describe, often rearranging words into amusing anagrams. “Words, words, words” becomes “sword, sword, sword,” for instance — it’s a cheeky device that often works in the show’s favour, providing a tantalizing glimpse into the creative masterminds of Lepage and Côté as a single creative unit. At present, those surtitles are an infrequent presence, and yet so much inform the aesthetic of the show that they seem both under- and over-used.

Though Côté centres himself as Hamlet‘s protagonist, brooding and paranoid, he and Lepage also amply explore the wider world of this dysfunctional family, and its ebbs and flows towards and away from the tortured prince. Many of Hamlet’s strongest moments occur away from Hamlet himself: audiences will likely leave this one talking about the sharp synchronicity of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern (played by Connor Mitton and Willem Sadler), or the fluid, heartbreaking writhes of Ophelia (portrayed with wide-eyed curiosity by Carleen Zouboules). Horatio, too, gender-swapped in this production, is a highlight, danced with total strength and power by Natasha Poon Woo, lively against Côté’s introspective Hamlet. With each pas de deux, Côté and Woo explore what it means to combine the genderedness of partnered dance with this complex friendship between men — it’s a fascinating experiment in gender-neutral casting.

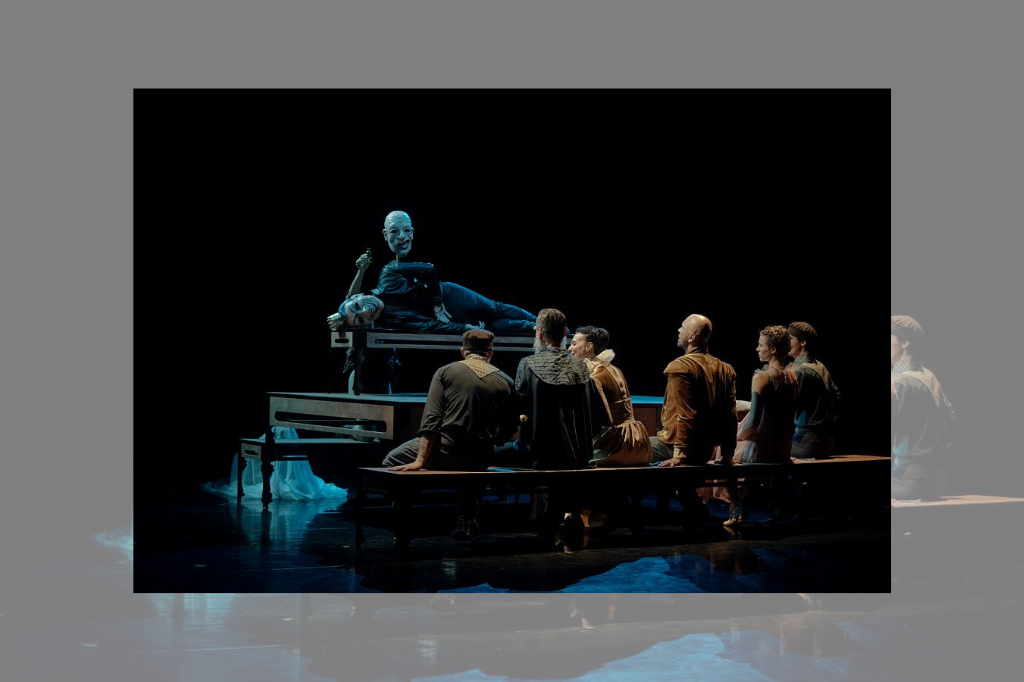

It’s when the dozen or so chess pieces of Hamlet come together that this world feels its most dangerous and inspired. The final duel between Hamlet and Laertes (a magnetic Lukas Malkowski) brings everyone together in a can’t-look-away-swordfight, one enhanced by ribbons attached to the weapons, evoking blood, or, in the case of the white ribbon, truce. As Gertrude looks on (a lovely and graceful Greta Hodgkinson), it becomes all too clear that this is a no-win war between generations. Another moment earlier in the piece similarly uses its ensemble to great effect: masks worn on the backs of dancers’ heads suggest a two-facedness that perfectly aligns with the dramaturgy of Shakespeare’s play.

All in, this is a rich, thoughtfully conceived Hamlet, one that will feel accessible to fans of both dance and text-based theatre. That said, I found myself missing the scenographic flexes that Lepage has made his trademark over the years — while that craft shines through in scenes like Ophelia’s suicide, I felt it less in the connective tissue between scenes. Simon Rossiter’s lighting design, while functional, at times lacks surprise or sophistication. Outside of one sequence that makes smart use of strobe, Rossiter bathes the stage in a flat white light, leaving the utilitarian set (Lepage is credited as the show’s designer) to pick up the slack. Côté and Lepage use that set to its fullest potential, playing with texture and opacity by way of pillowy sheets, but the absence of variation in the lighting felt like a significant omission to me on opening night. As well, be warned: folks sitting in the first ten or so rows of the Elgin Theatre may struggle to see the floor of the stage, upon which much of Côté’s lyrical choreography unfurls.

This not-quite-wordless Hamlet is scheduled to play international stages in the months to come, and will no doubt live a long life beyond this premiere in Toronto, a first outing this city’s lucky to have experienced, kinks and all. To dance, or not to dance the age-old tale of Hamlet? In time and with further development, the answer will be obvious.

Hamlet runs at the Elgin Theatre until April 7. Tickets are available here.

Intermission reviews are independent and unrelated to Intermission‘s partnered content. Learn more about Intermission‘s partnership model here.

Comments