REVIEW: Jungle Book reimagined needs a little reimagining

Living off a subway line that’s often going “towards Kipling,” I doubt I’m alone in thinking frequently about The Jungle Book. For acclaimed British-Bangladeshi choreographer Akram Khan, the connection to Rudyard Kipling’s 1894 short story collection is more personal. Khan stated in a 2022 interview that playing the titular role in The Adventures of Mowgli at 10 years old continues to be a central part of his identity as a performer and dancemaker.

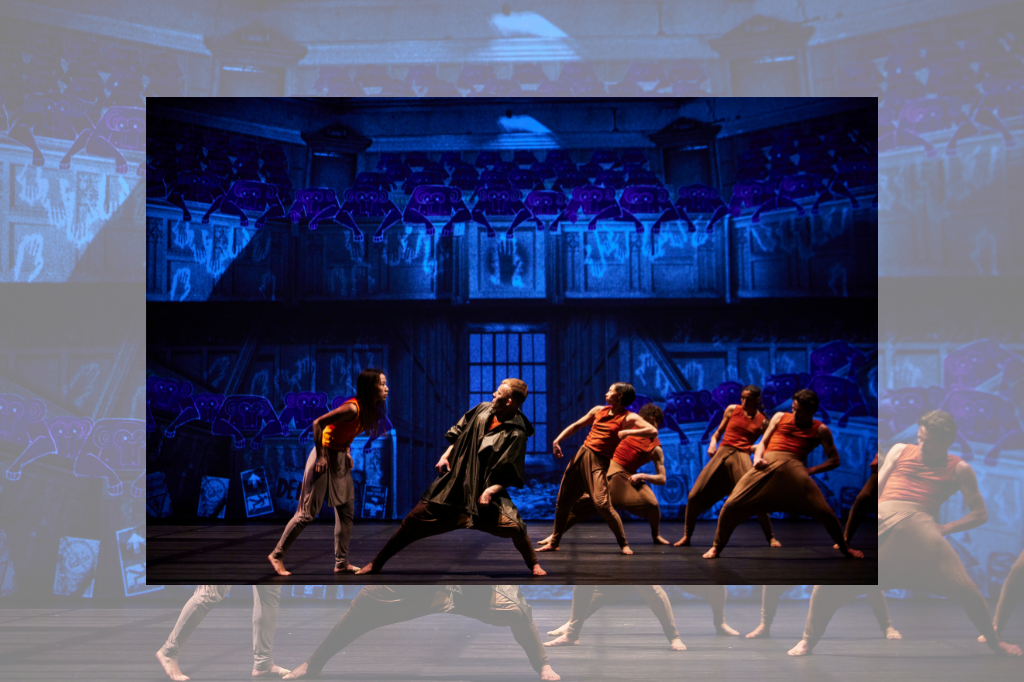

That interview is in the program notes for Jungle Book reimagined, a performance by the Akram Khan Company that ran at Canadian Stage’s Bluma Appel Theatre from October 12 to 14. Most will be familiar with the Disney adaptations of Kipling’s story, perhaps a reason why the show was billed as “a stunning piece of contemporary dance that the whole family will love.”

But Khan takes a pointedly different approach to a story criticized for its colonialist content, one that feels more adult-oriented in content and presentation. His Jungle Book takes place in a not-so-distant future, where climate refugees escape ecological devastation, and humankind’s relationship with nature is more fraught than ever.

Indeed, Akram Khan “reimagines” a historically complex story into a two-hour exposé on the environmental catastrophe. Jungle Book’s captivating visual effects and dynamic physicality brought the opening night audience to their feet. But as the choreographer’s first billing as director, Jungle Book’s storytelling doesn’t always live up to Khan’s skill as a dancemaker.

Courtesy of lighting designer Michael Hulls, Jungle Book begins with a green light slowly rising from the back of the stage, revealing the silhouettes of dancers who almost seem still. The soundtrack, by composer Jocelyn Pook, crescendos to the sudden sound of a thunderclap, then cuts to black. Stillness over such a long duration is dramatically impactful here; it may be the best moment of the performance.

From the darkness, pre-recorded animations by Adam Smith and Nick Hillel play on transparent screens encompassing the stage’s front and back. People are crowded onto boats, escaping from a flood that has seemingly upended Paris’ Eiffel Tower and Dubai’s Burj Khalifa. Mowgli, a girl in this version, falls off into the water. Saved by a whale, she’s brought to the shore of a strange new land.

Though at times heavy-handed, these animated vignettes provide narrative context, interloping at key moments. They’re woven throughout, the layered screens giving depth to a mostly-bare stage (besides stacks of cardboard boxes).

The majority of Jungle Book is told by a cast of voiceover actors larger than the onstage ensemble. They give human voices to tigers, gorillas, and elephants. The dancers then embody those animals, moving along with the words. While the voices debate casting Mowgli back into the ocean, for instance, a group of dancers make monkey-like movements in support, banging their fists on the ground and rolling to the floor.

This narrative device plays out to mixed success. It’s often difficult to understand, as the reliance on voiceovers omits the possibility of lip-reading.

More importantly, however, the choreographed animal movements are often quite repetitive. Khan’s contemporary movement style usually blends Western training with kathak, a classical technique of South Asian performance including intricate gestures and a grounded, intense physicality. Yet the movement to verbiage here often feels like throwaway pantomime; it lacks the kind of rhythmic interplay with speaking voice that drives the work of choreographers like Robert Battle and Ohad Naharin.

Jungle Book seems to operate under the assumption that text is necessary to tell a story. Yet its most compelling moments ditch the pantomime for dance sequences that echo Khan’s better work. When a monkey character brings out a jukebox and breaks (not breakdancing; this is the preferred term of practitioners!) to a series of distorted news audios, it does more to explain the ridiculousness of Mowgli’s circumstance than the preceding story. Later, a calm unison phrase emphasized by small gestures and pensive orchestration is performed alongside an animation of Mowgli and her mother, encapsulating her loneliness and communicating a desire for returning home.

It’s unfortunate that these small moments can’t make up the whole production. There’s a compelling case for Khan’s desire to revise this story that is so meaningful to him, yet so fraught. But with all of its effects, drama, and spectacle, this production unfortunately finds him a little like Mowgli again: lost in translation.

Jungle Book reimagined closed on October 14. You can learn more about the production here.

Intermission reviews are independent and unrelated to Intermission’s partnered content. Learn more about Intermission’s partnership model here.

Comments